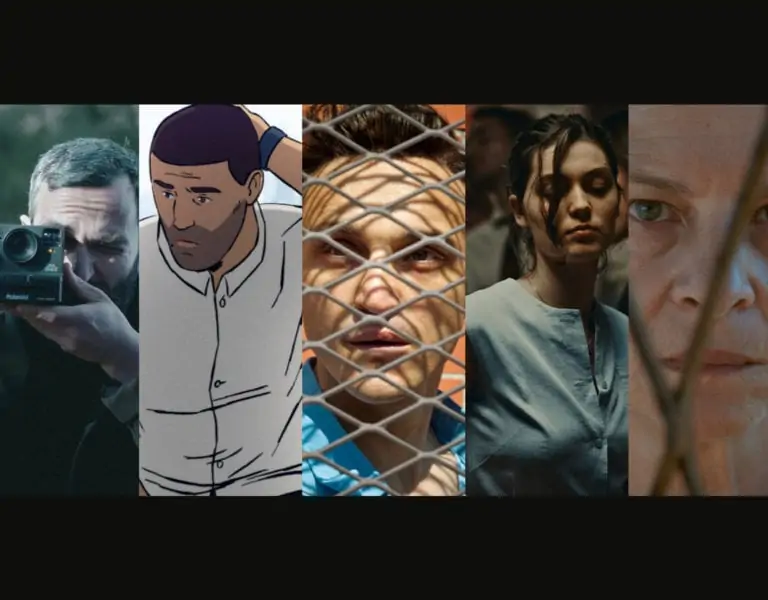

The word “shoot” applies to both guns and cameras. As we recoil from and grieve over the terrible images beamed into our sitting rooms, here are various examples of the film industry subverting military technology by adapting it for the much better purpose of entertaining and educating.

With grateful thanks to Dennis Fraser MBE GBCT, Barry Read, Gary Godkin, Ian Ogden GBCT, John Adderley and Roland Phillips GBCT for their invaluable help and advice.

World War I

Anamorphic lenses were developed by Henri Chrétien to give a wide-angle view from the periscopes mounted on tanks. Polyvision, the IMAX of its day was the three camera, three projector, three screen system used to produce the final reel of Abel Gance’s 1927 masterpiece “Napoleon”. It’s said to have motivated Chrétien to adapt his lenses to be used in front of the camera or in combination with a single projector, thereby achieving the same result. History doesn’t relate whether or not the projector was a Vinten.

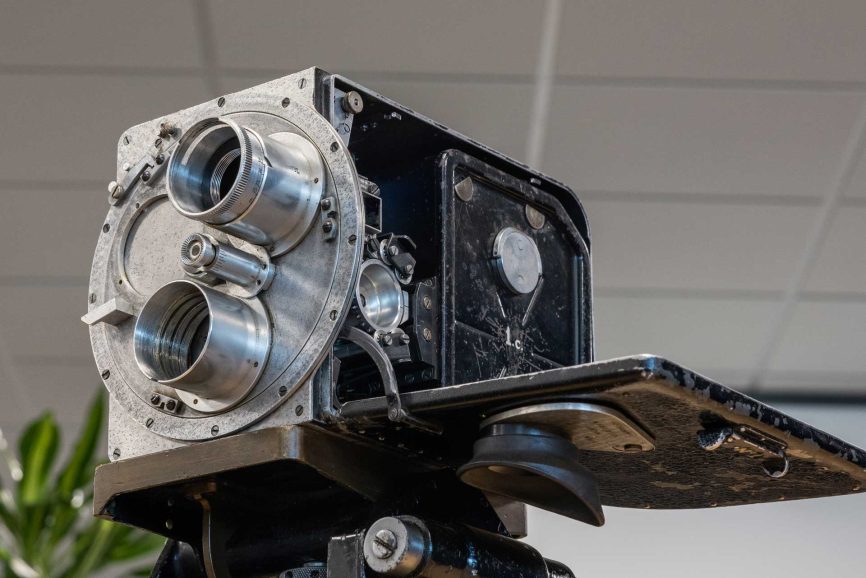

William Vinten, founder of W Vinten Ltd – originally based in Wardour Street, the heart of London’s film district – started out manufacturing projectors in 1909. With the outbreak of war, the company joined Sopwith in order to design and build Model B, a cine camera that could be operated while hanging over the side of an aircraft. His Model H was launched in 1928 to compete in the sound era of “the talkies”. A modified Vinten Model H was used in the Baird Studio at Alexandra Palace along with a variety of equipment for the world’s first high definition public television tests in 1931.

Frank Hurley, who accompanied Ernest Shackleton on his ill-fated expedition to the South Pole, joined the Australian Imperial Force as official photographer for both world wars. He took great risks to achieve the perfect shot and many of his acclaimed aerial photos were taken by means of attaching his camera to the gun mount and sitting astride the plane. He abhorred the misery and destruction of war and courted controversy by treating his images in order to illustrate this. Believing that single images were limited, he made composites intended to give an accurate impression of the grim reality.

World War II

The original Moviola Crab Dolly was inspired by US bomb loaders, after an air force officer spotted its potential for use in movie production. It was cobbled together with forklift parts and warehouse tyres and subsequently adapted. The bomb loader’s ability to lift and load 750 lb bombs into the back of an aircraft transferred seamlessly to carrying heavy cameras, not least the Alexa 3D rig used on Martin Scorsese’s “Hugo”.

The war created an increased requirement for reconnaissance cameras and Vinten’s military contracts secured a world market presence for reconnaissance work, particularly with the F24 camera. The relatively lightweight and extremely sturdy Newman Sinclair, stalwart of the BBC, was a popular wartime camera due to its easy handling. This sturdiness was severely put to the test by Stanley Kubrick on his 1971 film A Clockwork Orange. In order to film the subjective shot of Alex’s attempted suicide, the camera was wrapped in polystyrene and flung from the roof. It took six takes before it achieved the desired effect by landing on its lens and smashing. Apart from the lens, the camera was unharmed.

Pinewood Studios was requisitioned during the war years for the Army Film and Photographic Unit, the Crown Film Unit and the RAF Film Production Unit. The AFPU set up a training school for its cameramen there and the Vinten Model K Normandy, originally painted in camouflage green, was designed for their use. It featured a triple lens turret and 100 or 200 feet daylight loading spools of film. A memorial plaque honouring fallen members hangs in Pinewood.

The Crown Film Unit, led by the Boulting brothers, Richard Glendinning and David MacDonald, was tasked with making propaganda films for the Ministry of Information, one of which “Desert Victory” won an Oscar. It charted the struggle between Rommel and Montgomery and used footage from the Desert and North Africa campaigns. New York’s Museum of Modern Art called it “.. vindication of the documentary film as the powerfully educational and inspiring force it can be.”

From the other side of the Atlantic, director John Ford was head of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services. He too made propaganda films and documented the D Day landings on Omaha Beach, for which he was awarded a Distinguished Service medal. Unfortunately, the majority of his footage was accidentally dropped overboard. Frank Capa, acclaimed war photographer was also at Omaha Beach and suffered equally bad luck with his photographs. Only eleven of an alleged one hundred and six survived a processing error in London. Known as “The Magnificent Eleven”, they influenced Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski’s decision about the look of Saving Private Ryan.

Cult film director, Russ Meyer served in WW2 as a U.S. Army combat cameraman. His standout feature Faster Pussycat, Kill, Kill! is not a memoir about his time in action, nor was it a blockbuster. This expression was first used in 1942 to describe a bomb large and powerful enough to destroy a block of flats. The dreaded word deadline refers to the line drawn around captured prisoners of war. Crossing that line would risk certain death. Crossing the line is never a good thing.

Post war

The Moviola continued to serve and proved a highly stable platform for the enormous Photosonics high speed camera, originally developed to document the NASA space programme. Adolph Furrer founded the Acme Tool and Manufacturing Company in the 1920s. It supplied contract machines initially, but moved to making specialised equipment for Walt and Roy Disney. When the US began developing missiles in the 1940s and 50s, the company’s expertise with precision cameras led them to expand into this new field. Photo-Sonics Inc. was formed in 1952 to develop and manufacture high speed instrumentation cameras and associated systems. Its products is still used by the military and film industry today and the company was awarded a Technical Academy Award in 1980.

ITV started broadcasting in 1955, leading to a great expansion in the industry and higher demand for crew. Many had completed military service, which proved good training for the hierarchy and professional demands of a film set and brought their structurally oriented work ethic and terminology with them. Call Sheets the origins of which lay in Officer Commanding Orders and Movement Orders became standard, as did the language of the Walkie Talkies: Going ten one. Roger that. Over.

Vinten equipment also became standard for television studio and outside broadcasts. Queen Elizabeth II inadvertently precipitated the invention of the Vinten Outside Broadcasting Dolly by requesting a less intrusive dolly for the filming of her 1956 Christmas Day Message at Sandringham. It ran on either solid or pneumatic tyres and was able to glide silently across the royal living room.

The American slating system uses the NATO phonetic alphabet, which became effective in 1956. The expression NG commonly used in the film industry, but not much welcomed, is alleged to have been imported from post-war occupied Japan where heavy censorship was applied to any information considered inappropriate. This particularly applied to drama and films. Its use continued after occupation and eventually spread from the broadcasting industry to become common parlance.

The Moviola, still going strong, played a small, but vital role in the 1966 Raquel Welch film Fantastic Voyage. Look closely at the scene where the “precision handling device” is solemnly wheeled in to inject the shrunken submarine into Benes’ body and you’ll spot a remarkable likeness to a Moviola painted white. Inventive, resourceful and practical on the part of the art department; dear to the producers hearts – assuming it was at no extra charge!

Fast forward to the ’70s: Who can forget the iconic opening shot of the second scene of Chariots of Fire tilting up from bare feet and legs to the white shirts and shorts of young men running along the beach to Vangelis’ epic score? One minute and eleven seconds of unforgettable footage was achieved by rigging the camera with bungies on the back of a 2CV. This was before the invention of stabilised heads and entirely thanks to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of Dennis Fraser MBE and his team. If only he’d had a Louma – the first remote crane and a real game changer. It’s named in honour of its two creators Jean-Marie Lavalou and Alain Masseron, who were inspired when they had to shoot in the cramped confines of a submarine during military service. A tenuous connection to the adaptation of military equipment for the purposes of film making, but a good example of the inventiveness of camera crew.

Another of Dennis’s tricks was to strap cameras to boat masts, thus keeping the shot steady as it followed the exact movement of the craft, even when it changed tack or the water turned choppy, making it impossible for gimbals to cope. If only he’d had a gyro! Designed to stop a boat’s roll and pitch, gyroscopic stabilisers are spinning flywheels, which work on the same principle as a bicycle. As long as the wheels keep spinning, you stay upright. They were also used to stabilise tank gun turrets in WW2 and technology has now advanced to stabilising the elevation of the gun, thereby keeping the line of sight steady whilst firing on the move. A Panasonic engineer named Oshima is credited with coming up with the idea of camera stabilisation whilst on a busman’s holiday in Hawaii in 1980. He was part of the research and development team working on gyro sensors for car navigation systems. The bulky video camera wobbling about on his colleague’s shoulder led to him applying the technology to camera stabilisation.

The military are generally keen to co-operate on war films and will provide advisors, as long as the script shows them in a positive light. This was not the case with Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 satirical anti-war film Dr. Strangelove, a commentary on the Cold War and the political and military institutions, who literally held the fate of the world at their fingertips. The Vietnam war had been raging since 1955 and there was no point in requesting the Pentagon’s co-operation, but sometimes the film industry just gets lucky. B-17s served as cameraships and a B-52 was superimposed on shots of their low level attacks. Otherwise, their only appearance is as an unnerving and inaccurate shadow of the B52s. The Production Design team, led by Ken Adam, who had served as a fighter pilot in the Second World War, had to imagine the interior of the B52s sent to bomb the Soviet Union. So the story goes, they did this by comparing the cockpit of a B-29 Fortress with a single photograph on the cover of a book called “Strategic Air Command” by Mel Hunter and then scaling up the geometry accordingly. It was a lucky fluke, but nevertheless an exceedingly accurate one. So much so, that Adam later recounted that the colour drained from the faces of some United States Air Force personnel on a visit to view the reconstructed B-52 cockpit. They said that “it was absolutely correct, even to the little black box which was the CRM (Crew Resource Management).” Apparently, Kubrick was sufficiently concerned to summon Ken Adam to explain that he hadn’t infiltrated a B52 base, thereby risking an investigation by the FBI.

How “Auntie” did her bit

John Logie Baird first demonstrated his “televisor” in 1926. Philo Farnsworth called his 1927 electronic version the Image Dissector. In 1931, the forerunner of Sports outside broadcasts was achieved by using a mirror drum camera mounted in a caravan to film the Derby.

November 1936 saw the launch of the BBC, transmitting from Alexandra Palace for 4 hours a day, but only in the London area. The advent of the Second World War in 1939 brought a complete shut down for fear that the signals from the Alexandra Palace aerial would serve as a navigation aid to the German air force. Most research went to the war effort. However, the aerial served an important purpose in both jamming and picking up signals, which enabled the Bletchley Park codebreakers to confirm that the Luftwaffe were using a radio-based navigation system to guide them on their bombing raids.

A group of EMI engineers, who had been responsible for developing the BBC’s television service, moved to setting up a radar system that would later be used by Bomber Command. Research on communications from the 30’s contributed greatly, as well as advancing television’s technical progress. The components common to both were transmitter valves and cathode ray tubes. The reception and transmission of ultra-short radio waves was as important to the development of radio location, or radar as we now know it, as it was to broadcasting. Britain’s early warning system in the event of air attacks was named the “Chain Home” network. It was a series of radar stations around Britain’s shores and was brought into operation on 3 September 1939, the day war was declared.

The BBC continued to serve the country covertly by transmitting code messages to undercover operatives and resistance fighters in occupied Europe. An elaborate system of codenames, hand-delivered mail and security checks was introduced. They usually consisted of a few phrases dropped into a programme or foreign language news bulletin, but there was always the worry that bizarrely worded messages would spoil the programmes and risk discovery.

Music also played its part in secret messages broadcast to Poland. The unlikely codename “Peter Peterkin” was used by Polish Government Officials, who would provide a record of a particular piece of music. The Polish news would then run for a shorter time, so that the record could be played. What could possibly go wrong? Plenty, as it transpired, including playing the wrong side or forgetting to play it at all. Producers took to sitting in on the programmes to ensure this didn’t happen and that the quality conscious, but oblivious, engineers didn’t reject the records on the basis of a scratch or two, thus risking the wrong bridge getting blown up.

Lines from Paul Verlaine’s popular poem “Chanson d’automne” (Autumn Song) were included in pre-agreed programmes or news bulletins. This was the Special Operations Executive favoured means of communicating with the French Resistance. At 23.15 on the night of June 5th 1944 the SOE’s coded message instructed the resistance fighters to start sabotaging railway lines in preparation for the D-Day invasion the following day. The unlikely missive was “Blessent mon coeur d’une langueur monotone“, which translates as “Wound my heart with a monotonous languor”. So poetically French!

The BBC re-opened in 1946. Since then, it has reported on the Cold War, followed by the Korean, Vietnam, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syrian, Ukraine, Israel/Palestine conflicts and many others.