Café culture

A new riff on the ‘brief encounter’ romance, A90 gives a contemporary twist to a classic tale, as cinematographer Leon Brehony explains.

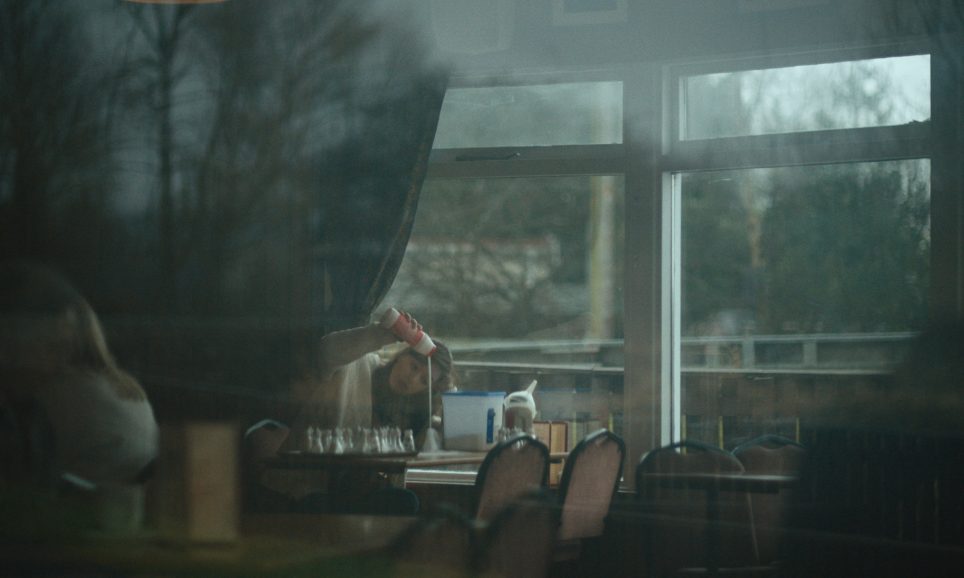

A roadside café on the A90, which stretches across northeast Scotland from Edinburgh to Fraserburgh, is the unassuming setting of Olivia J. Middleton’s short film, shot by Leon Brehony. Find out how Middleton and Brehony brought the story of a fleeting romance between a waitress and a customer to the screen, taking inspiration from classical filmmaking.

British Cinematographer (BC): How did you get involved with A90 and what appealed to you about the story being told?

Leon Brehony (LB): I was lucky enough to be involved with A90 from its conception. The director, Olivia J. Middleton, and I have been making films together in some way or another for the last 11 years (and have been in a relationship for 10 of those years).

To keep ourselves sane during the first 2020 lockdown we watched a tonne of films that had always been on our combined watch-lists. One night after a double bill of Sally Potter’s Orlando and Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express, Olivia felt inspired and started working on an idea about a young woman working in a roadside cafe in North-East Scotland, who develops feelings for a mysterious stranger who frequents the cafe in the evenings.

What appealed to me was the concept of the story taking place in an in-between ‘netherworld’, inhabited by people on their way to somewhere else and the protagonist Annette, who feels trapped in this liminal space and longs for the larger world beyond the dual carriageway.

BC: Take us back to your initial conversations with Olivia. What was her vision for the look and mood of the film, and what new perspectives did you add?

LB: Orlando and Chungking Express set things in motion narratively, but never felt entirely appropriate in terms of style. Another Wong Kar Wai film, In the Mood for Love was much more in keeping with the tone of the film we were making.

Olivia is a big fan of classical filmmaking and the discipline of formal cinematic language. She was confident early on that the story should be told with as few spoken words as possible, instead allowing the characters’ body language, gesture and glances to build the romantic tension – so the challenge was to build a filmic vocabulary which would enhance this subtle storytelling.

BC: Did you have any creative references for the look?

LB: We watched a lot of films for inspiration and put together a bank of photographic references. The idea of the look evolved naturally throughout prep, but the biggest visual inspiration came when we watched Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts. The subject matter was similar but what resonated most was the restraint and naturalism in the filmmaking. They allowed the camera movement to be dictated by the blocking and not the other way around. I was a fan of cinematographer Robert Elswit ASC before seeing this but there was something timeless in the look of Desert Hearts and the way that the light just seemed to exist in the space without feeling over-manipulated.

A strange last-minute reference was Ridley Scott’s American Gangster shot by the late Harris Savides ASC – particularly the muted colour palette and low key/low contrast aesthetic with deep creamy blacks.

BC: How long did you have for prep and what did it entail?

LB: From the first iteration of the script, which was developed and funded through BFI in association with Short Circuit/Screen Scotland, we had about five months of prep. Because we live together, Olivia and I essentially discussed the film all day, every day, for this entire period. We would swap references, talk in-depth about the story and the style and generally eat, sleep and breathe A90.

We were initially meant to go into production in October 2020 but due to complications with the funding body we ended up pushing to February 2021, which was a huge blessing as those final few months were a crucial creative turning point for the approach and look of the film. We also found time to shoot another short in January 2021 so it was a very intense winter.

BC: Were you involved in location scouting? How did you decide on the filming location and what were the benefits/challenges of it from your perspective?

LB: Being from Aberdeenshire, Olivia knew the A90 quite well and already had an idea of a couple of potential locations. We drove up and down the A90, stopping for coffee at a few different roadside cafes before coming across The Horn, which had a distinctive curved windowed facade and life-size ceramic cow on the roof. It seemed perfect as the wood-panelled interior, nostalgic design elements and lighting fixtures hadn’t been modified in decades. There was a timeless nature to the space that suited the story, which was reminiscent of a cafe where Olivia had worked as a teenager.

On our first recce, Olivia shot three rolls of Portra 400 35mm film using the producer Carys Evans and a friend as stand-ins for the characters. We constantly returned to these stills as reference throughout prep as they represented the initial visual inspiration that came from being in the location with fresh eyes.

BC: What did your camera package comprise and what made you choose it?

LB: We shot on the ARRI Alexa Mini LF provided by MTP, who were supporting the film. We chose to shoot UHD 3.8k and crop to 1.66:1 instead of full frame/open gate as we wanted to keep a decent depth of field so this felt like a nice middle ground between full frame and super 35.

We opted for Canon K35 lenses for their classical 1970s aesthetic, which we got from No Drama in Glasgow. The benefit of the K35s is that they retain their distinctive character even when stopped down. Olivia liked the idea of using depth of field to subtly indicate the growing romantic tension between the two characters. We went through the script scene-by-scene and decided to shoot T4-5.6 for the beginning, T2.8 when the characters begin to be drawn together and T1.4 for one scene in the middle when they reach their emotional peak, going back to T4-5.6 for the final act when the cold light of day ruins any hope of their blossoming relationship.

BC: What were the biggest challenges of the shoot from a cinematography perspective and how did you overcome them?

LB: The biggest challenge was balancing the exposure throughout the entire cafe. I like the style of ‘lighting spaces, not faces’ so I opted to try and balance the practical lighting so that we could shoot 360 degrees at all times at a minimum stop of T5.6.

It was also important to the story that the overall balance of the lighting be low enough that we could pick up the car headlights through the windows. We spent a lot of time in the café during prep, experimenting with lighting ideas. It was helpful to be able to observe the natural light at different times of day in varying weather conditions. I’d played with pushing the EI on a few different projects and felt that it would be right for A90 so we shot at 2560EI for the whole film. I love the colours and contrast on the Alexa sensor when you push the dynamic range towards the highlights and away from the shadows, and I like the noise that this introduces. This also meant that we only had to aim for 15 f/c inside the café as opposed to the 50 f/c that would have been required at 800 EI.

BC: How did you use framing and composition when portraying the blossoming relationship between the two women?

LB: After we decided on The Horn as our location we revisited it about once a month with the other HoDs and a stills camera. We went through the space over and over again, trying to exhaust all the possible options of camera angles and frames that the location had to offer. Olivia’s filmic tastes definitely dictated the compositions, which all tended to fall within the same parameters: medium/long lenses (we never shot wider than a 55mm, apart from one exterior shot of the cafe), wide eyelines and depth within the frame. Olivia used an optical viewfinder to set the camera position and we would design the shot so that we could pan and tilt with the characters as they moved through the space, often capturing several different angles within the same static position. We used a slider for one scene and handheld occasionally as it felt appropriate for specific moments, but mainly the camera lived on sticks.

BC: Take us through your general approach to lighting the café.

LB: There was quite a bit of trial-and-error in prep when it came to finding the right light bulbs. The lampshades in the cafe were mounted quite close to the ceiling, which meant that conventional globes would blast light in every direction. Eventually I found some frosted 25w mushroom bulbs which would emit a beautiful 30-degree cone of light, especially when supplemented with a bit of haze.

We would diffuse, cut or remove the 25w bulbs depending on which direction we were shooting. Before the first shoot day gaffer Lewis Hanlon and I gelled some of the existing fluorescent fixtures with ND in order to balance everything. For most scenes we bounced dimmed 650w fresnels off the ceiling, walls or tables in order to create shape.

In the kitchen we taped up some black card in order to create a skirt for the ceiling mounted fluorescent lights. For daytime scenes we embraced natural light, occasionally laying 12×12’ sheets of bleached muslin on the ground outside and we swapped out the 25w mushroom bulbs for 60w incandescents in order to get a bit more level as the spill wasn’t as big an issue during the day.

BC: Were there any especially difficult lighting setups in A90?

LB: One of the most difficult scenes to light was the dance sequence that takes place two-thirds of the way through the film. This part of the story takes place at closing time in the café, which needed to be reflected in the lighting. The scene was staged in the darkest part of the space and by far the hardest to light naturalistically – plus it needed to feel romantic and not too murky but also allow for 360 degrees of shooting. We turned off most of the overhead lights, gaffer taped a flexible 3×1’ Falconeyes Hybrid LED to the ceiling, and draped several layers of unbleached muslin underneath to make it feel as source-less as possible.

BC: Who did the grade and what look did you seek to achieve?

LB: The film was graded at No.8 by colourist Alex Gregory who is a magician. He brought such a high level of finesse to every frame – whilst keeping our original intentions towards a muted palette, subtle colour contrast and deep tonal values. I’ve gone on to work with Alex a few times since and I never want to go without him again. He’s one of the best.

BC: What was your proudest moment from the production process?

LB: At the end of the final shoot night we fell behind schedule and had just over an hour to shoot the entire dance scene. We had to throw all of our plans out of the window and shoot everything handheld. We found angles that worked, shot a take, then moved on to another angle. The cast and crew fell into a kind of adrenaline-fueled flow state and it ended up being one of the most fun scenes to shoot – and we wrapped on time.

BC: Were there any lessons learnt that you’ll take onto your next short film?

LB: What I learned on A90 is the value of being as prepared as possible. When resources are limited it can be difficult to pull everything together, but I was lucky enough to spend months with the director, delving into her creative imagination and vision for the film, which gave me a confidence that couldn’t be bought. We revisited the location again and again, trying out ideas, taking hundreds of photos and developed an understanding of the way the light moved throughout the café. We developed a fluency that allowed us to experiment and get all of our bad ideas out of the way long before we turned over on our first slate.

Watch A90 on Shorts Of The Week’s YouTube channel.