PIXEL PERFECTION

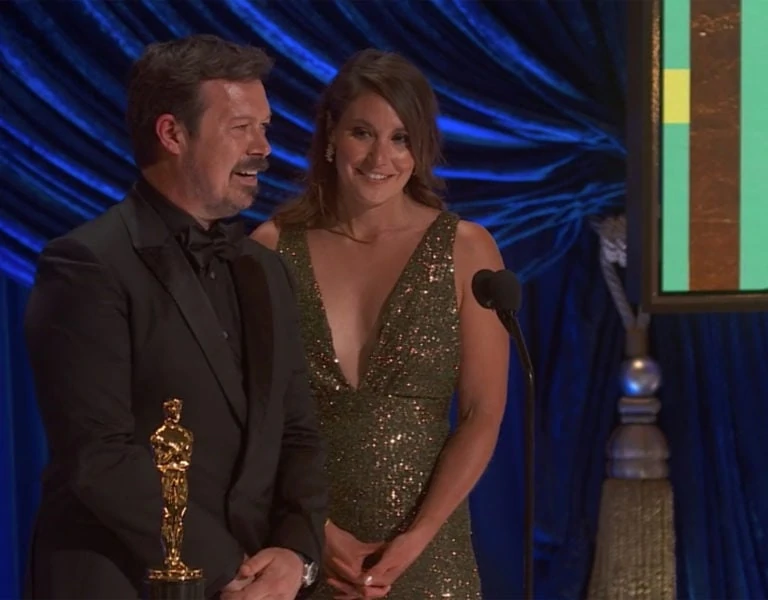

Jarred Land has spent his career in close collaboration and connection with filmmakers, supporting the execution of their vision with powerful and ground-breaking tools.

Jarred Land runs RED Digital Cinema, the company whose 4K camera went from scepticism to admiration on a run of prestige movies like David Fincher’s Oscar-winning Mank and series like The Queen’s Gambit. Since 2013, Land has led a team focused on precedent-setting technology for filmmakers.

Land didn’t found RED but joined Jim Jannard before the launch of the first camera and during the hardcore, technology banging sleepless nights part of the story, where a small group failed, learned, succeeded. From the first conversation Land had with Jannard and still today, the focus is on providing a more complete tool for filmmakers.

Born in Edmonton, Canada, Land’s father ran gas stations and shopping malls, imbuing in him an entrepreneurial spirit. The teenage Land’s passion was mountain biking which he segued into his own bike courier company in Vancouver.

A chance encounter with a client inspired him to take up videography using the Panasonic tape camcorder DVX100. “I couldn’t go to film school because I was running my company and biking 100km a day, so I set up a bulletin board for help,” he says.

Basic by today’s standards (and pre-YouTube), these text-based forums attracted communities to discuss all sorts of topics. Land created DVXuser.com (for which in those early internet days he had to build the server in his closet) “just so I could ask questions.”

The site became one of the world’s largest online communities, making Land a powerful influencer. Leaving the bike business in the hands of friends, he began to learn cinematography as camera crew on documentaries and features (he is credited as additional footage cinematographer on Steven Spielberg’s Munich, 2005). While snowboarding, he met the son of a Vision Research executive. In those pre-Phantom days when it was primarily a crash cam, Land was offered a role sharing their technology with filmmakers, but he and his friend Nick Bicanic decided they’d rather take a Vision Research camera and experiment with it further, diving into a realm where frame rates were not locked down.

On return from filming a documentary in Sierra Leone (Shadow Company, 2006), he got a call from Jannard, founder of Oakley sunglasses, inviting him to come to its Lake Forest headquarters.

Jannard had joined DVXuser and recognised in Land a fellow film enthusiast who could make things happen. Not just an avid camera collector, Jannard shot most of Oakley’s commercials and was unsatisfied with the direction digital cameras were headed.

“When I met Jim, he was designing a watch. It was the most incredible thing I’d seen. It may seem rather trivial, but that watch convinced me I wanted to be part of anything that man was thinking of creating,” Land says. “We had no real idea how to make a camera. Graeme Nattress (still RED’s CTO) was with us, Stuart English was there, and we hired consultants and just started the process. We were a small, totally obsessed group that really wanted to create this camera. We literally slept under our desks, Jim included, in a large industrial warehouse. We started bringing a prototype camera alive; we aptly named it ‘Franky’ after a few revisions.”

The RED One launched in 2007. While it wasn’t the first 4K digital cine camera (that was Dalsa’s Origin), it was more compact, more affordable and devised a new way of marketing to the community, using reservations to gain attention. It worked.

“Our motivation wasn’t disruption, it was simply to make something better than what was out there, respecting film in the process,” says Land, “and making something much more accessible to filmmakers.

“Even though camera technology was trending away from film and had seemed to settle on 1080p as good enough, we felt like it just wasn’t a suitable replacement for 35mm. We knew we had to make a massive push and start at 4K.

“Recording a frame of 4K was cool but recording it at 24p, let alone 60p, takes an enormous amount of data. That’s why we devised REDCODE as a way to process it, which was one of our most important developments. Everything we’ve released since has been built on the edge of what is possible,” he notes.

“Luckily, advances in GPU acceleration led by companies like Nvidia have propelled file editing from our cameras forward. It’s much easier now to process 4K, 8K, and beyond thanks to companies that brought horsepower to the table. They played a hand in pushing cinematography forward.”

RED has long been accused of being fixated on resolution. “All pictures filmed on 35mm or 65mm had more resolution than the filmmaker probably needed,” he says. “But at the start of digital filmmaking, you were stuck with 720p, or if you were lucky, 1080p. Many deemed 4K unnecessary when we started, but fast forward to today and you can’t even go to the store to buy a 1080p TV. We don’t want resolution to be the story,” he insists. “We just want you to not have to think about it. And that goes for frame rates and dynamic range too.”

RED’s position proved compelling, influencing every other camera manufacturer to release higher resolution imagers. Arguably the market’s hand was forced by Netflix’s demand for its originals to be shot in 4K – a bold move that followed the debut of House of Cards in 2013, made by Fincher with a RED Epic Dragon.

Fincher had made The Social Network a few years earlier, an award-winner and first major Hollywood picture shot digitally and on RED by Jeff Cronenweth ASC. The director has used RED on every picture since and continues to play a pivotal role in the company’s R&D.

“Fincher is really one of the biggest keys to our success,” says Land. “Just when I get comfortable, he pushes me further. He knows more about technology than any other director that I have worked with, and he understands its role in telling a story better than anyone. With House of Cards, he pushed Netflix towards their current direction (of high spec deliverables). That was the moment when everybody really had to start thinking about 4K – and I’m sure the same will happen to 8K.” says Land.

“Fincher will tell us exactly what he wants. The first camera we made with him, he rejected in the end because of a strong aversion to the number of wires dangling around the camera. So, we started over. The original camera was incredible, and eventually became the Panavision DXL. It was perfect for 99% of filmmakers, just not the 1% of Fincher.”

Land notes Fincher was also the inspiration for RED’s monochrome sensor, which he wanted for a commercial. It became a low volume staple in RED’s line-up with every new design. A few generations forward, Erik Messerschmidt ASC used the monochrome sensor on Mank, for which he received the Oscar in 2021.

Land’s abiding relationship with filmmakers has guided the development of the industry-changing tools for which RED is known. His focus on the advancement of creative technology includes over 50 patents to his name.

“At heart, I want this to remain a garage operation with a can-do attitude. Engineering is by far our biggest expense. We have FPGA and ASIC teams, mechanical and electrical engineers, and an incredible product team that makes creating things much easier than relying solely on outside parties. When it’s time to create something new, we have the in-house talent and that gives us a good shot at getting it done.”

Land believes when it comes to the image, the sensor and the glass are the most important things about the camera. “You need great internals to make sure you are recording all the information correctly in the most efficient way possible. But the actual mechanical camera body is what you become most intimate with. The body should start small, and you build it up, whether for studio or handheld.”

RED’s Komodo features a global shutter which took the firm three years to perfect. “We knew directors had a problem shooting cine quality pictures with crash cams and fast-moving footage because they told us so. Global shutter is the answer, but traditionally with a global shutter you lose too much dynamic range. Our team cracked it, so now the DR between a global and rolling shutter is about the same.”

The recently launched Raptor gives filmmakers something else they asked for: more frame rates. Raptor is capable of 120 fps 8K. “Often we’re solving little problems that some filmmakers didn’t even know they had, and that leads to a much bigger vision in the future. Every innovation we create is truly in service of the filmmaker, giving them abundance instead of just good enough so they can focus on the image telling the story, and not being confined by the limitations of technology.”