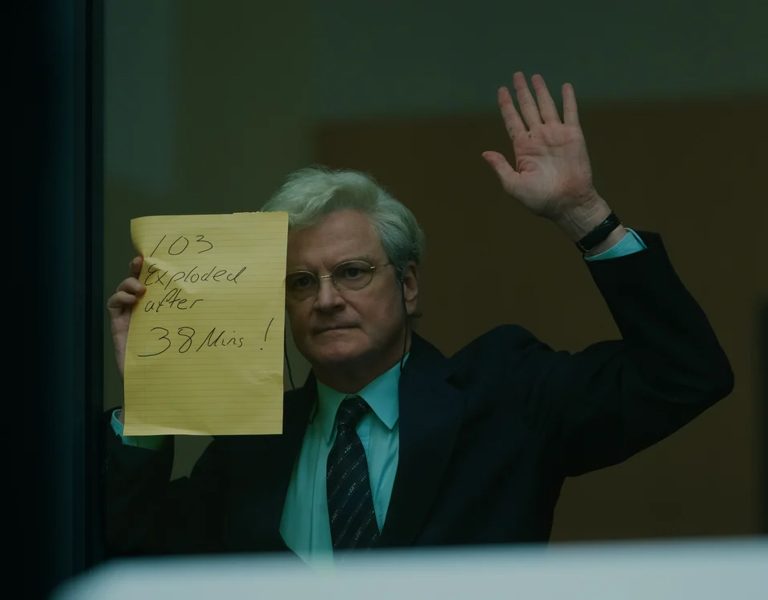

Did anyone know that Arri has a single D-21 camera modified with a hand crank? Anyone who’s a big enough fan of the late, great Tony Scott’s famously kinetic style that they’ll tolerate shooting at ISO 200 might be quite interested. Presumably, the existence of said D-21 is not forbidden knowledge as it reportedly finds its way to set a couple of times a year, but that’s just the sort of obscure background knowledge that one might expect to emerge from an in-person visit to Arri’s headquarters in Munich.

On June 30, 2023, the company hosted its a summer party for its Europe-based employees, including people from recently-acquired lighting specialists Claypaky. The event presented a perfect opportunity to find out about not only modified D-21s but also the birthplace of all modern Alexas. The factory tour discussed here is something the company describes as usually being almost impossible, given the delicate processes involved, and has politely requested that people shouldn’t ask. On this occasion, however, a group of DPs (and your narrator), who would later give a seminar at the event, were offered a unique opportunity to look at the production process of what’s possibly the world’s favourite digital cinema camera.

Design and admin work currently takes place at the same building as camera manufacturing, an imposing block in black engineering brick on Herbert-Bayer-Straße (lighting is built in Stephanskirchen, about 70 kilometres to the south-east). The company moved to the purpose-built complex at the end of 2019 having previously been at the same location on Türkenstraße, closer to the centre of town, since its founding in 1917.

Some of the most sensitive parts of the manufacturing process lurk behind no-photography signs for reasons we’ll discuss below, and anyone entering the manufacturing area is required to use anti-static precautions to minimise the potential for damage to sensitive electronics. The factory was, understandably, filled to the brim with Alexa 35s during our visit. The construction of the camera around a central cooling chamber was very visible as the PCBs were stacked around the metal central core. A lot of modern cameras have room for air to move through a heat sink behind the sensor, though few are built to keep the electronics so well-isolated from environmental contamination.

The chassis are machined from solid billet in the company’s in-house machine shop (no castings are used in modern Alexas). Sensors, inevitably, are sent out for manufacturing, although even some later stages of what would normally be done in a semiconductor fabrication plant are kept under Arri’s roof. When Arri received its Scientific and Technical Academy Award for the ALEV III image sensor in 2017, people from ON Semiconductor, which designed the sensor, joined Arri representatives on stage. It was a rare show of magnanimity in an industry where many manufacturers are, for some reason, coy about the heritage of outsourced components.

The ALEV series, and that industrial collaboration, goes back to sensors built in the 2000s; in 2009, for instance, the Academy also recognised the ALEV II built for ArriScan. ALEVs are not high-yield devices, meaning that a large proportion of them will not have the characteristics Arri desires – or, frankly, they’re rejects. That happens most when semiconductor designs push the manufacturing technology close to its limits.

One way Arri mitigates those losses is to test each sensor before it has even been separated from the circular silicon wafer on which it was made. Doing that avoids the cost of packaging each sensor before testing it, which involves the attachment of hundreds of microscopic gold bond wires. Testing semiconductors on-wafer to minimise bonding costs is not new, though Arri reports it has developed ways to perform tests by exposing the sensor to test images during the process. The novelty of that approach is what made the cleanroom in which it’s done a firmly no-photography area, which is a shame, because semiconductor wafers containing image sensors exhibit a sort of infinitely recurring spectral reflection rather like a sort of rectilinear compact disc.

It’s perhaps a little ungenerous to concentrate too much on the sensor, given that the subsequent electronic image pipeline apparently involves something like a thirty-stage process. PCB manufacturing is done out of house, though much of the cleverness is really in the firmware, not the hardware. All modern cameras, from cellphones to Alexas, are highly reliant on processing to produce subjectively pretty pictures, suppress noise, and work around inevitable manufacturing variability in the sensor. Cameras in the later stages of manufacturing spend time staring at controlled light sources which allow the firmware to null the speckled pattern caused by the variable sensitivity of individual pixels, something that’s characterised for each primary colour and at various intensities.

Tests, among much else, involve a vibration test, as well as cycling every camera in temperature from -20°C to +45°C. At that point, the cameras go off for finalisation and packing, and the visitors went back downstairs for a beer and a miniature bundt cake. At the front of Arri’s new building is a museum of cameras including examples of the D-21, with Grass Valley’s on-board recorder. Given the one at Uxbridge is possibly the only hand-crankable digital cinema camera on the planet, we can only hope that the company keeps its historic cameras as carefully as it builds its new ones.