Home » Features » Industry Wide Shot »

MEETING THE CHALLENGE

The nation’s facilities are beefing up human and technical resources to meet extraordinary demand.

The record levels of inward investment production spent on film and high-end TV last year are astonishing but even more astonishing is that everyone expects 2022 to top that. 2023 could set a new high bar.

The £4.713 billion spent in the UK on major projects during 2021 is a continuation of the trajectory which has seen the UK a favoured production hub for studio and streaming TV shows. The figure is double the level reached during the low-water mark of 2020 and signifies a surge in productions greenlit as COVID-restrictions eased.

As a result, the domestic postproduction sector has never been busier.

“Work bounced back really quick after we shut down for four months [along with the rest of the industry from March 2020],” reports Sam Margaritis, MD, Digital Orchard. “Work gradually started and last year was probably the busiest we’ve ever had across film. It was a little bit insane at points.”

“Demand is unprecedented, but it shouldn’t come as a surprise,” says Simon Craddock, CEO, Onsight. “The creative industries are always first to bounce back after a recession. There’s a bow wave of work coming through, and we’re all scrambling to cater for it but let’s not complain. This is a good position for the industry to be in.”

Not only is the volume of productions at an all-time high but they tend to be bigger in scope, run for longer and are technically demanding.

“Go back 15 years and everyone wanted to get on a Harry Potter,” says Mark Purvis, MD, Mission Digital. “Now projects like that are happening in their dozens and lasting for half a year with a heavy demand for VFX. These shows often involve complex onset workflows with multiple cameras in different formats across multiple units shooting in different countries and time zones. All of that media needs to be consistently managed.”

Combating the skills shortage

The sheer demand has created a skills shortage which is the most pressing concern across every role and sector of the industry.

Margaritis hears that some crew on some productions would jump to the next gig before the assigned end of the first one. “You don’t want to lose an eight-month project for the sake of spending the final week on your existing production but it’s awful for producers if there’s no availability to cover,” she says.

“We’ve been able to bring in a whole host of new talent all from under-represented groups and all with zero industry experience. We train in-house and then they learn on-set. Because of the high demand, the ability for someone to move up the ladder is accelerated. It means many more people will reach their goal of being in senior positions, even heads of department, in the coming years.”

Digital Orchard works with 50 regular freelancers – a number that has remained steady over the last few years. It reaches out to diversity and inclusion groups run by The Production Guild and the BSC as well as local communities to source new talent which are then funnelled through the Digital Orchard Foundation.

“We try to not make it about socio-engineering, but we do want to bring in more female operators and people with diverse and ethnic background including those with neuro divergence since the industry remains very white and male,” Margaritis says.

Part funding body, part lobbying group, part training and networking facilitator, the DO Foundation is designed to both pump-up and streamline the onboarding of underrepresented groups in film and television, as well as to fill the gaps in current provision through new events, advocacy, and training.

“The challenge is honing talent to get it up to speed to fill the shortage,” agrees Craddock. “We hire some experienced people, such as senior sales personnel, as well as take on graduates to train them internally.”

Mission Digital is also on a mission to increase its freelance pool. “I don’t think there’s a company in the UK with as much depth in visual imaging technicians as us,” says Purvis. “We already employ over 40 and they are all trained in-house so we’re able to guarantee a level of service and consistency.”

The related issue is the rising cost of talent because of wage inflation. It’s economics 101: skills shortage plus high demand and the price goes up.

“For indie filmmakers the extra cost of staff coupled with the cost of COVID precautions are making life more difficult,” says Craddock. “Financing the gap is easier for studios.”

Workflow origami

Mission Digital has recently worked on Amazon series The Wheel of Time, which was shot primarily in Prague and The Power (also Amazon) filmed partly in South Africa for which Mission provided on set DIT services as well as a Digital Dailies Lab based in the new Shepperton Studios facility, processing footage from the UK and abroad.

“A show might shoot in London, editing in New York, posting in LA with VFX in Vancouver and Adelaide,” Purvis says. “This type of complex workflow is common. Everyone works hand in hand around the world and around the clock to meet deadlines and that all needs to be orchestrated.”

Much more of this work is being handled in the cloud. Mission is partnered with Amazon and has a direct 10G connection into cloud bucket S3.

“It’s a fairly standard studio requirement to see media pushed to cloud which is why we’re further investing in technology for productions to work on high fidelity VFX files hosted in the cloud.”

Built from the ground-up in house at Mission Digital during the pandemic and dubbed Origami, the cloud management system is already operational and enables VFX teams anywhere around the world to work on shots.

“One thing we hear repeatedly from clients who use our DIT daily service is that they never need to worry about their image when it is with us. They know they have complete ownership of the image. With this platform we’ve extended that service guarantee to any VFX vendor around the world.”

Infrastructure upgrade

Cheat is opening a fifth grading suite later this year, maintaining its position as one of the biggest finishing houses in the country.

Toby Tomkins, founder and senior colourist, points to the increase in the volume of media acquired at 4K and higher resolution and in Raw that is requiring facilities like his to upgrade storage systems to cope.

“You want to be working off a full resolution debayered 16-bit media in the grading suite not proxies or transcodes so that means very high-end workstations, storage and network infrastructure.”

Cheat has tripled its Network Attached Storage system from Synology and runs DaVinci Studio on Linux supermicro servers and workstations fitted with the latest Nvidia Quadro graphics cards.

“Commissions from AMC, FX or Netflix are generally going to be Raw. Even British terrestrial TV drama is acquiring Raw. I don’t think there’s much difference that you can see on screen between raw and ProRes but there is a slight advantage for keying and VFX. Also, if you’re shooting with a very high ISO or something is incorrectly exposed then shooting raw can give you slight edge in recovering some of that detail.”

Not so long ago and producers would be charged a premium for shooting 4K UHD (just as they were when HD was introduced) because of the knock-on storage and processing costs. But not anymore, at least not at Cheat.

Tomkins says, “We don’t charge differently depending on source media nor do we charge more per Gig or per Terabyte of media when it comes to transfers although a different finish such as HDR or SDR pass does add more time in the suite.”

Distributed production

In March, the UK Screen Alliance withdrew the specific COVID restrictions on film and TV post-production. Although various COVID guidance developed by the BFC, broadcasters, and Pact remain in place (it is still mandatory to consider COVID-19 within a company’s risk assessment), in practice these are falling away. What that means is that the sector is presented with a chance to reset the working and home life balance.

“We believe a hybrid working model is the way forward, with a strong sense of being together, teaching and learning from each other, and creating the right culture – which at the same time doesn’t necessarily mean being in the office Monday to Friday 9-til-6,” says Vittorio Giannini, MD/EP, Freefolk.

Anecdotally, few editors want to go back to the way things were. Many already moved outside London pre-pandemic and many more did so during the past couple years. Nor do they need to be in a city centre suite, often with no-one else in attendance, perhaps until performing the final client review (which can also be achieved with live streaming tools).

“Some of our staff are fully remote, purely because of geography and others want to come into the studio two or three days a week. Our technical set up means that there’s total flexibility and we work with our staff to ensure that they are able to work both remotely and in the studio.”

The very nature of a business like Digital Orchard or Mission Digital whose technicians are on-set and location is already distributed to large degree. Facilities with even an element of lab work or editorial – especially finishing – will find it harder to shift to a fully remote (cloud-connected) organisation.

“It’s important to keep our feet on the ground and scale up with a core of good freelancers without raising our overheads,” Craddock says. “There are elements of post-production that can be operated remotely and where we can we will, but in terms of DI for features we feel creatives want to work as close to each other as possible. It’s a people business and whilst you can do prep remotely, a DP and their colourist do want to be together and feed ideaS off each other in person.”

Nor is working from home the ideal it is often presented as. Many staff simply lack the space to WFH and while flexibility to be with family is important, others do want the separation of home from working life.

“I feel that we are experiencing almost an even more ‘pressured’ working environment now, post-COVID,” says Natascha Cadle, creative director and co-founder, Envy. “A lot of our employees have requested to keep coming into work so that they can separate their home and work life more efficiently. It’s an individual choice.

“You just don’t learn as efficiently from colleagues over Zoom. We all thrive on social interaction which is essential to every aspect of our emotional and physical health. Our industry is a very social and collaborative and that is not always easily achieved when you work remotely.”

Virtual production yet to impact

Mission Digital is the only company responding to this feature noticing an uptick in virtual production. That’s partly because it is neighbours with Garden Studios which has a 4,800 sq.ft space with permanently installed LED volume.

“We’re seeing Garden being busy but overall I don’t think VP is hitting the demand that everyone thought it was going to hit,” Purvis reports.

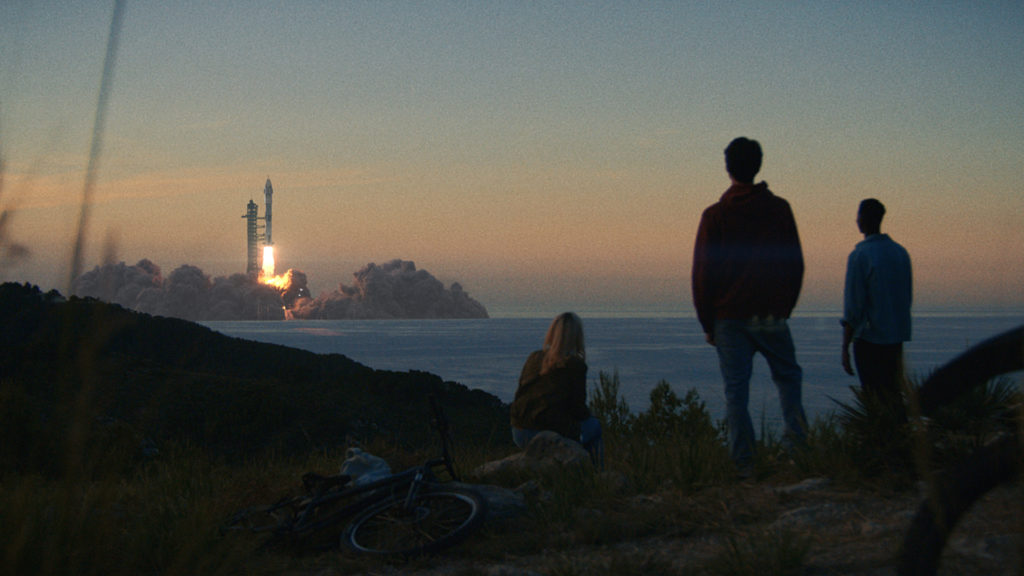

This could be to do with cost since virtual production services have not reached a level of mass market or standardisation that will bring its use within reach of more budgets. It is more likely however that there’s a gap between the noise surrounding a few high-profile productions like Netflix period drama 1899 (shot on a revolving sound stage in Berlin) combined with the enthusiasm of vendors selling kit like LED screens, servers, and games engines, and the reality which is that filmmakers may actually prefer to spend time on location.

“I don’t think film crew find being on a VP stage all of the time particularly inspiring,” remarks Purvis.

Even advocates of the technique, like AJ Sciutto, director of virtual production at Magnopus (whose credits include The Lion King), says VP is not suitable for every production.

“VP is not a silver bullet,” says Sciutto. “There are a lot of people who are trying to force things into a VP workflow that they shouldn’t. There is absolutely a tactility to locations you don’t get inside of a volume.”

Even The Mandalorian and 1899 make use of regular sound stages alongside a volume. This can be to accelerate schedules (by shooting different scenes simultaneously) or for aesthetic reasons. “Shooting an entire show in a volume can look too sterile,” says Sciutto.

More likely is that certain scenes will be staged within a volume, again for various reasons of economics or practicalities of achieving the shot for VFX. Greig Fraser ASC ACS (who designed the virtual production template on The Mandalorian) used LED screens to supplement extensive location work on The Batman.