Kinetic Camera

Special Report / Grip Hardware & Camera Movement

Kinetic Camera

Special Report / Grip Hardware & Camera Movement

BY: Kevin Hilton

Moving the camera in filmmaking has rarely been constrained by the equipment available. Once the problem of camera noise had been solved, directors and cinematographers were able to stage moving shots that created moments of drama and tension or revealed a character's emotions. During the 18 years of British Cinematographer, grip hardware has reached higher levels of sophistication to allow ever more ambitious shots.

A new era for camera movement got off to a suitably high-profile start with Russian Ark (2002). It was conceived by director Aleksandr Sokurov as a single, continuous take to carry the audience through the Winter Palace in St Petersburg, encountering various characters from the city's past. It was shot by cinematographer Tilman Büttner, also recognised as one of Europe's leading Steadicam operators, in a single 99-minute take made possible by the combination of a Sony CineAlta HDW-F900 recording on to hard disk and a special rig designed by Büttner himself.

A shorter, but no less ambitious, continuous shot features in Joe Wright's 2007 adaptation of the Ian McEwan novel Atonement (DP Seamus McGarvey BSC ASC). The scene in which the characters, played by James McAvoy, Daniel Mays and Nonso Anozie, arrive at the Dunkirk beaches was achieved through using a Steadicam in conjunction with other hardware. Operator Peter Robertson initially rode on a small electric tracking vehicle before stepping off that to walk to a bandstand. He then moved round a boat, up a ramp and on to a rickshaw before walking past the pier and into a bar.

Steadicam, Garrett Brown's baby, has developed since the 1970s, with several new models and adaptations along the way. In 2015, the modular M-1 was shown in conjunction with the Exovest skeletal support vest designed by Steadicam operator Chris Fawcett. His first design for the rig was the Steadiseg, created in conjunction with Ulrich Kahlert, who invented the hands-free steering system for the original Segway.

Fawcett feels the Steadicam Volt horizon assist system has brought extra freedom for operators. But, as much as Steadicam has become almost the generic term for body-worn moving camera supports, other companies have developed their own takes on the idea. Glidecam countered the new Steadicam Ultra² at IBC 2007 with the X-10 stabiliser for handheld work, designed to operate with the 2000 and 4000 Pro systems. At the 2014 NAB show, Glidecam introduced the X-20 for heavier cameras, which has been followed by the X-30 and X-45. In the UK, Mr Helix has been a prime mover in the camera department, producing the Ready Rig, as well as handheld and remote hardware.

Glidecam also produces other grip equipment, including the Camcrane 200. The crane has long enabled directors and cinematographers to create big, impressive moving shots that give a broader view of the action or home in on a specific aspect or character in a scene. Film fan Quentin Tarantino is a noted user of cranes. In Django Unchained (2012, DP Robert Richardson ASC), Django (Jamie Foxx) has survived a typically bloody Tarantino shootout and surveys the carnage. As he moves from a corridor into a room, the camera rises and rotates so that it is looking down on Django as two figures appear either side of him. In his most recent feature, Once Upon A Time in Hollywood (2019, DP Robert Richardson ASC), Tarantino uses a crane to reveal where the down-at-heel stuntman played by Brad Pitt lives.

Los Angeles gets the high-rise treatment at the beginning of La La Land (2016, DP Linus Sandgren FSF ASC), during which director Damien Chazelle pays tribute to the type of shot used in Busby Berkeley musicals. The camera tracks horizontally along a line of cars, with different music coming from each, until finding the actor who begins the song 'Another Day Of Sun'. It then weaves through the vehicles for various set pieces before craning up to reveal LA in the distance.

The opening of David Fincher's Panic Room (2002, DP Conrad Hall ASC/Darius Khondji AFC ASC) has the camera establishing the setting and oncoming threat by moving over banisters and downstairs, before travelling into a door lock. This was realised by combining physical movement on a Technocrane with CGI to achieve the transition. Other leading brands that have made shots possible over the past nearly 20-years are ARRI, which recently introduced the Hexatron off-road crane positioning system, JL Fisher with its Jib and Cross Arms and Panther's Jibglider and Pixy camera crane.

Panther is also known for its dollies, including the Classic Plus, P1 and, most recently, the S-type. The dolly is a workhorse of film production, without which many a movie would have been static, and has evolved and matured with time. Some dolly shots simply follow a character but, as in Boon Joon Ho's Oscar-winning Parasite (2019, DP Hong Kyung-pyo), that can still say a great deal. Others are showier. Take the Arc Shot, much favoured by Michael Bay and Christopher Nolan.

In Nolan's film's, including The Prestige (2006), The Dark Knight (2008) and Inception (2010), all shot by DP Wally Pfister ASC, the camera travels round characters in circles, building up the turmoil or confusion they - and the audience - are experiencing. Then there is Spike Lee's trademark double dolly shot, which creates the sensation of everything moving around a stationary character. It features in most of his joints, but most recently 25th Hour (2002, DP Rodrigo Prieto AMC ASC), Inside Man (2006, DP Matthew Libatique ASC) and BlacKkKlansman (2018, DP Chase Irvin CSC).

Not that recent camera movement has all been about big, dramatic gestures. As much as David Fincher can marshal all the large-scale hardware available to him, he is also a master of the 'imperceptible', the small move achieved through subtle tilts and pans. The fluid head in particular has made these easier and smoother to accomplish. Among new heads that appeared over the life of British Cinematographer Magazine are the Vinten Vector 750, Microdolly Model III, Ronford Baker Atlas 7 and 40 and, coming right up-to-date, this year's ARRI SRH-360 stabilised remote head. In 2017, Vinten and Sachler claimed to have reinvented the tripod with the Flowtech 75, featuring what were confusingly described as the fastest ever tripod legs.

A new addition to the camera movement arsenal is the slider. This apparently very simple but in fact very flexible piece of kit allows the camera to be moved in a noteworthy way but without too much effort. Both big and smaller, independent productions have discovered the benefits of the slider, which Jeff Lawrence, managing director of Ronford Baker, has called the most significant development in recent years.

Handheld shots do not look like going away anytime soon, particularly while Paul Greengrass and JJ Abrams are still making films. The last 20 years saw this key element of moviemaking take on a new and often derided style in the form of 'shakycam'. With this, the camera not only moved in a more recognisably human way, but also sometimes positively juddered, as on the first of Abrams' new Star Trek series (2009, DP Dan Mindel BSC ASC). Greengrass brought his documentary background to bear with varying results on The Bourne Supremacy (2004, DP Oliver Wood) and Captain Philips (2013, DP Barry Ackroyd BSC), among others. Ackroyd's handheld expertise was used to particularly good effect for The Hurt Locker (2008).

Aerial shots continue to make bold statements, but helicopters and light aircraft have in recent years found a new challenger in the drone. These small flying pests have allowed airborne footage to be shot closer to the action and for less expense. Notable examples are: the motorbike chase along the roof of the Grand Bazaar at the start of Skyfall (2012, DP Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC) using Flying-Cam 3.0 Sarah, which won a Technical Oscar; and the pool party scene from Martin Scorsese's The Wolf Of Wall Street (2013, DP Rodrigo Prieto AMC ASC), shot by Freefly using a Canon C500 on a Convergent Design Gemini.

Of course, flight can also be simulated using cranes, as on Birdman, Or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance (2015, DP Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC). This eccentric Michael Keaton-starrer was shot as a continuous take, and also involved Steadicam operated by Chris Haarhoff. But it is closer in structure to Hitchcock's Rope (1948, DP William V Skall/Joseph Valentine) than Russian Ark, in that it was a sequence of long takes seamlessly edited together.

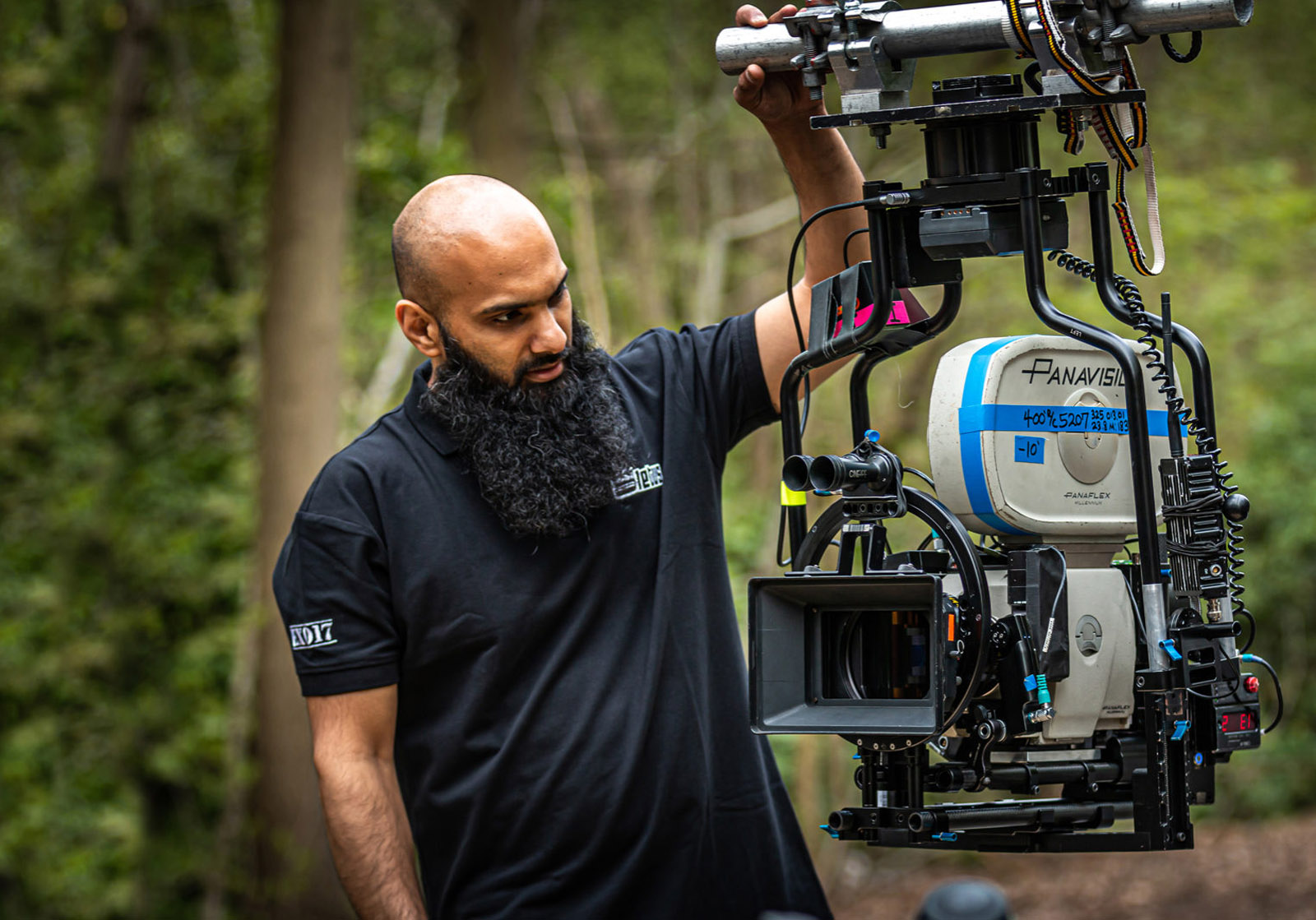

A similar approach was taken on Sam Mendes' 1917 (2019). To achieve the movement necessary to communicate the horror and confusion of trench warfare, Roger Deakins used a combination of moving camera technologies and hardware. In addition to a Steadicam, operated by Peter Cavaciuti, there was a StabilEye remote head, which Deakins controlled himself, and an ARRI Trinity stabilised rig operated by Charlie Rizek. The Trinity was designed by Curt Schaller, who describes it as three products in one, with the additional ability to work as a handheld gimbal.

Schaller calls Trinity a game-changer and it may turn out to be that. Whether it deposes the Steadicam remains to be seen, but what it does show is that cameras will continue to move in the next 18-years, as directors and cinematographers use grip hardware to add to the creativity of filmmaking.