The word “medicinal” is not usually used in the context of Hollywood’s (and London’s) late winter award season, unless one is perhaps contemplating something – cup of herbal tea, warm glass of milk, hot coffee, can of Red Bull, perhaps pharmaceutical – to either stay awake, get to sleep, or perhaps settle a stomach (or a hangover) after a long night of watching statues being handed out. Or in some cases, being one of the recipients.

But there the word was, used by Nick Offerman, who continued both his own personal award season streak, and that of The Last of Us in general, winning again for his guest-starring in the show’s “Long, Long Time” episode. In what is becoming the series’ most renowned instalment, both he and co-guest star, Murray Bartlett, find love at the end of the world – both the imploding one outside, and, as it turns out, in their own personal one, as well.

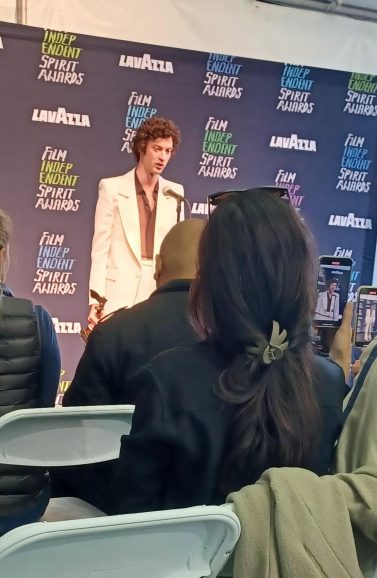

We reported on Offerman’s Emmy win last column out, and here he was now at the Film Independent Spirit Awards, held, as ever, in its sprawling tent on the beach in Santa Monica. The Indie Spirits – originally with a focus on movies made outside the studio system – have added robust television categories in recent years, and so it was that Offerman won for his turn as “Bill” in the Best Supporting Performance in a New Scripted Series category (though the addition of new categories in many such shows doesn’t necessarily tend towards brevity).

In accepting his award, Offerman made some spot-on comments about the episode being not a “gay story” but a “love story” – which quickly ignited the next morning’s showbiz headlines. In the press tent afterwards, he followed up by saying “it’s nice in this business when anything you do is medicinal.”

He referred to “good medicine” again later, and it was one of those cloud-breaking moments where you realise why there’s so much fervour to try and do this work, this collective storytelling in movies, TV shows, documentaries, et al. Because, past the frenzy of the always-uncertain economics, or trying to find an audience (let alone funding), past the incessant gauntlet of promotion, (for something that had the good fortune to get made at all), past all that, there’s the chance – that rare, but graspable chance – to make something that might actually matter, and change people’s lives a bit. Or at least give them comfort in an increasingly alarming and unknowable world.

Work that could make someone’s life, somewhere, a tad easier. Even if fleetingly. Perhaps, even, lots of someones.

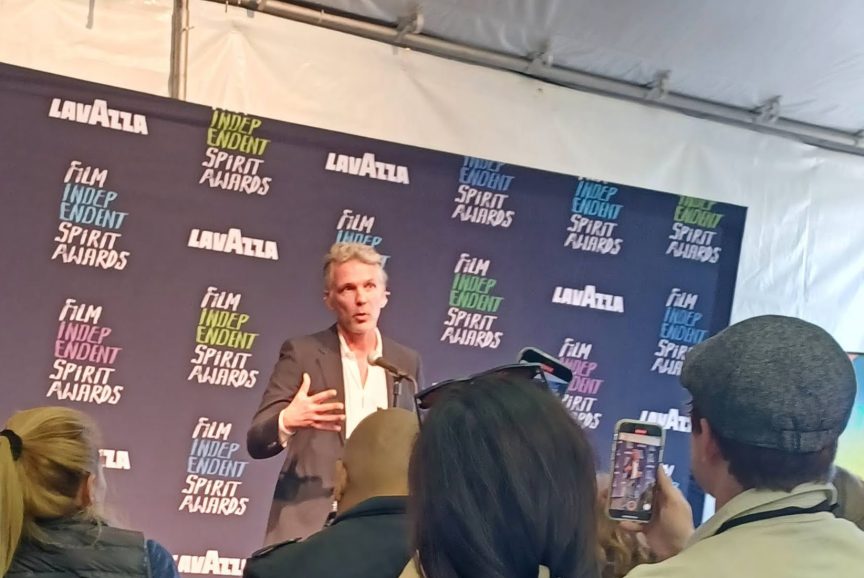

That was also on the mind of the best screenplay winner at the Indie Spirits, American Fiction’s Cord Jefferson, who followed up his surprise BAFTA win – “well, I was surprised,” he remarked to our question – who talked about the “diversity of people” who’ve responded to the film, after we’d asked about whether he expected such a personal project (“made for significantly less than 10 million dollars”) to find such a large and growing audience for a film based on a nearly quarter-century-old book.

The book was 2001’s Erasure, by Percival Everett, and Jefferson has remarked that he responded so strongly to it, he felt the book was written just for him. It was also much more complexly structured, as Jefferson noted a couple of weeks earlier on an Oscar-nominated writers’ panel at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Novels, he allowed, are “the artform that most closely resembles being in someone’s head”.

So here, he had to fashion a narrative that a lot of people’s heads could respond to, and based on the accumulating accolades (Jeffrey Wright, who plays the story’s main character, author Thelonius “Monk” Ellison, also won that same afternoon in Indie Spirits’ all-gendered Best Lead Performance category), Cord said the film has “resonated” with a much wider range of people than he might have originally guessed, with such a personal novel knocking around in his own head before he translated it first into a screenplay, then on screen.

Restorative viewing

But besides the resonance, there can also – quite literally – be the life-saving aspects of the work. Rather than mere hyperbole, this has been the case for Oscar-nominated documentary Bobi Wine: The People’s President.

The film’s DP Moses Bwayo (who co-directs with producer Christopher Sharp) recounts in an email that he first came to the project “at a downtown hotel in Kampala, Uganda, in late 2017”, when he was introduced to Sharp.

“I was a fan of Bobi Wine’s music,” he says of the singer-turned-politician. “He had transformed his life from the ghetto, and now he was in parliament to not only sing about the plight of the Ugandan people but also to enact laws that would change our situation.”

Bwayo himself was “arrested a few times, locked up in jail, and consequently shot in the face at close range. The morning after the Academy nominations were announced,” he continued, “Bobi, Barbie and three of their children had been under house arrest for a couple of weeks; as the news spread through the country, the military and police withdrew from their house. This film is a lifeline for Bobi, his family, and those struggling for freedom and democracy.

“The bravery of Bobi, and his wife Barbie, who have put everything on the line and face a relentless military dictatorship, is unimaginable. I don’t know anyone as brave as they are. They are true African heroes,” he concludes.

Bwayo himself – who shot much of the film on a Sony FS7, with “sound onboard as this was mainly a one-man crew in most cases” due to the volatile and dangerous filming situations – is now living with his wife in the US, and currently seeking political asylum.

Life-saving, resonant, or simply insightful, as Society of Camera Operators President and Awards chair Matthew Moriarty SOC said of the work that that group was honouring the night before the Indie Spirits: “These stories help us understand ourselves.”

The SOC was holding forth at the Directors Guild on Sunset Boulevard on the same night the SAG Awards were also unfolding at the Shrine Auditorium downtown (where the Oscars had occasionally found themselves, in years past). The SAG Awards underscored Oppenheimer’s increasing likelihood of nabbing a Best Picture Oscar by winning their Outstanding Cast in a Motion Picture award there and added to the momentum when the Producers Guild followed suit the next evening, similarly awarding the “split atom opus” its top prize.

The SOCs, however, ultimately tacked in a different direction. While the bulk of the show honours lifetime achievements among film, TV, live broadcast, unscripted, and mobile platform operators, as well as set photography, there are two “live” awards announced for operator(s) of the year in film and TV.

In the latter category, HBO’s The Last of Us prevailed once again, indeed, the selfsame episode that Offerman would win for the following night. In this case, it was Neal Bryant SOC with camera operator Carey Toner who were honoured, with Bryant thanking his entire crew, including the “day players”, followed by the emphatic thanking of the families whose support made shooting a “year-long show” possible.

In fact, with the previously announced lifetime honourees, there was a lot of thanking of spouses and family, too – it was one of the evening’s main themes: An acknowledgement of dinners and time missed while behind the lens, and a gratitude at the understanding that allowed them to pursue careers whose rigours and travel to places they otherwise wouldn’t have seen also “kept us all young”, as broadcast category lifetime honouree Dave Hilmer put it. “You couldn’t ask for a better job than we have as cameramen,” said the veteran, whose awards include nine Emmys, and whose work includes, among many other live credits, past broadcasts of Independent Spirit and SAG Award gatherings.

On the film side, however, the SOC strongly diverted from many of the season’s award trends, with nary a “Barben” or “heimer” in its contenders. Instead, the mix included films like the French-composer themed Chevalier; the Keira Knightley/Carrie Coon feminist “journalism procedural” The Boston Strangler; the Sony Classics’-released Carmen, a reworked, dance-laden update of the classic doomed love tale, set against a backdrop of cartels and border crossings; and chronicling another kind of doom, Netflix’s Leave the World Behind.

This year’s winner on the feature side, however, was Society of the Snow – which, like World, is also viewable on Netflix – about the 1972 plane crash that left survivors of a Uruguayan rugby team stranded in the Andes, with scant means left for their survival. The film was SOC’s biggest nod toward the rest of award season, as it’s also up for an Oscar in the Best International Feature Film category (though Anatomy of a Fall remains the heavy favourite there), as well as one for makeup and hairstyling.

Juanjo Sánchez SOC shared the award with B-camera operator Manuel Branáa, though only Branáa could show up, as Sánchez evidently faced visa problems. He thanked their entire crew, as well as cinematographer Pedro Luque SCU, who, Branáa said, “used the viewfinder as a time machine”.

Luque’s work on the film had previously been in competition for a Golden Frog at Camerimage, and also won the Goya – Spain’s version of the Oscar.

Tech triumphs

Meanwhile, time machines of a different sort were in evidence at the Academy’s annual Scientific and Technical Awards, held on the Friday evening of this particular award-heavy weekend, once again at its seemingly new permanent home at the Academy Museum.

Since the Sci Tech dinner is entirely honorific, for technical achievements that have furthered the art and craft of visual storytelling, all the “winners” are known well in advance – though sometimes the process of earning a plaque can take several years after submission to the sci tech committee for consideration.

Though the awards don’t really stop with the storytelling side; how those stories are shown (and heard) are honoured too, as this year’s bevy of auditory and laser-projection pioneers bears out (though the Blind Driver Roof pod – allowing a stunt driver to control a car from a caged seat on the roof of a moving vehicle, giving the thespian “drivers” in the picture vehicle itself greater performance latitude – was pretty cool, too).

The Academy noted the breadth of recipients, saying: “Awarded technology has been used in films like Gravity, Dunkirk, Avengers: Endgame, Avatar: The Way of Water and more with recipients from the United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada, Belgium, Japan and New Zealand.”

Ahead of the awards, Jed Harmsen, head of cinema and group entertainment at Dolby Laboratories – one of the evening’s most widely honoured companies, this go-round – wrote to say not only were they “deeply honoured and humbled” at the recognition for innovations in service of “unlocking more immersive cinematic experiences” but that their “commitment to supporting storytellers remains unwavering, and we look forward to continuing to push the boundaries of entertainment in the years to come.”

Or as this year’s lively host, Natasha Lyonne said, “in these divided times, there’s one thing we can agree on – and that’s Dolby.”

Though it was also noted, with some bemused irony, that we were listening to the various Dolby achievements via what was still a two-channel playback system.

And as it turns out, paying one’s dues can sometimes be as hair-raising a process on the technical side of showbiz as it usually is on the creative one, as Gregory T. Niven, honoured for “his pioneering work in using laser diodes for theatrical laser projection systems”, thus speeding up the transition for use of that technology in theatres, highlighted. He recounted tales of company bankruptcies and needing to essentially squat in office space for six rent-free months (reminding the landlord that the dangerous materials they had on site would be more dangerous still, for whatever tenant followed, unless they were allowed time to properly dispose of them), all while waiting for the rest of the industry to catch up with them.

‘70s soul

Of course, sometimes the industry catches up, and then rumbles on past, on to something new, if not always better.

Such has been the case for various “golden ages” in Hollywood, when a confluence of filmmakers, audiences, studio support, and economic conditions, all came together, at least for a while, to create astonishing strings of what turn out to be classics.

The ‘70s, of course, are viewed as one such age, and one reason given for the way Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers has been resonating with audiences (and award shows) this season; because it harkens back to the more personal, character-driven stories of that era. Of course, the story is also set in that era, too.

Da’vine Joy Randolph picked up another accolade at the Indie Spirits in the supporting performer category for her work in the film as Mary Lamb, a quietly grieving yet grounded mother, who happens to work at the same private school where Dominic Sessa’s Angus Tully hopes to have a kind of Last Detail-esque outing in nearby Boston, when he is “held over” at school over Christmas break, as his own mother’s attention is spent instead on trying to please a newly installed husband. Thus he’s left under the watchful eye – one of them, wandering, and thus a character note – of Paul Giamatti’s also lonely instructor, Paul Hunham.

Rizzo also won in the breakthrough performance category, thanking his castmates (and director) for “having patience” with him and “hearing” him while he worked on this first breakout role. This was also a “breakout” for winning cinematographer Eigil Bryld DFF, in the sense that while he’d prepped several projects with director Payne before, this was the first one to come to fruition.

We asked him if he’d made particular choices to make the story look or feel like one of those earlier films from the decade in question, given that he was shooting digitally. But he mentioned that in retrospect, he’d concluded it wasn’t so much the equipment that was important back then, but rather the “freedom of thinking” that made the cinema of that era so special. So it was that approach – allowing himself a wider latitude to how he would capture or light the visuals, or solve problems on the spur of the moment – that carried him through this first full collaboration with the man who is currently Nebraska’s most renowned filmmaker.

Ahead lay the final doses of medicine – good, bad, or otherwise – for this year’s award season, and we’ll be back with a dispatch from Oscar night when we see you here next. Until then: @TricksterInk / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com