LIFE IN THE FAST LANE

When portraying a significant period of change in the life of ex-racer and famed automaker Enzo Ferrari, eliciting an emotional response from the audience was a priority for writer-director Michael Mann and DP Erik Messerschmidt ASC, whether they were immersing them in high-octane race action or the drama and struggles Ferrari faced in his personal life.

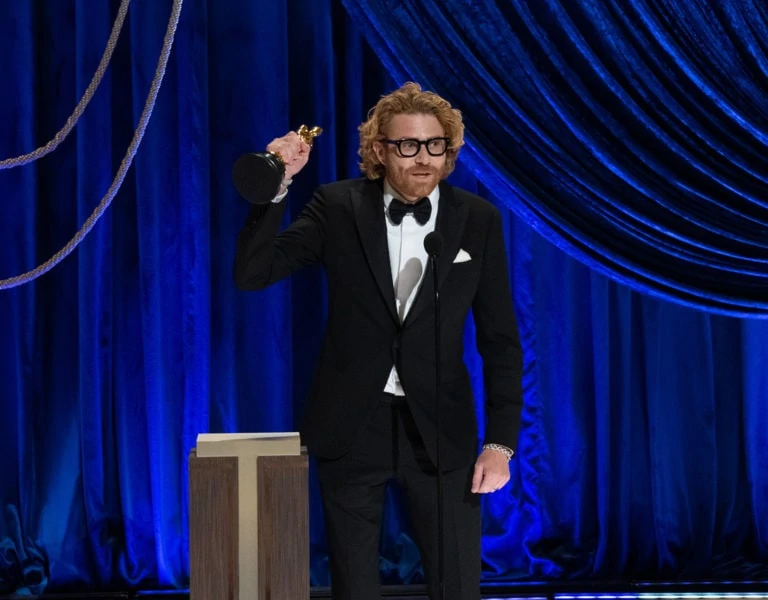

Wise words fellow cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth ASC shared with Erik Messerschmidt ASC have proven invaluable on a variety of productions, including one of his most recent, Michael Mann’s Ferrari. “He told me you have to be a generous collaborator; that your first job is to listen,” says Messerschmidt.

When working with Mann to bring his biopic about the life and career of ex-racing driver and car manufacturer Enzo Ferrari to the screen, listening to the writer-director’s perspective and filmmaking approach was fundamental, informing Messerschmidt that his role as a cinematographer was to create an environment for Mann to work within. “I light the set and present the palette to him, and then he can take it and run with it,” says Messerschmidt. “The frame is Michael’s property and it’s the cinematographer’s job to help reinforce the walls of his sandbox so he can work with the actors.”

Mann’s unique ability to “turn off the outside noise in the room” and focus on what he decides is important for the scene impressed the cinematographer, along with the director’s “tenacity and ability to not worry about the ticking clock and sun position” and make sure he gets the moment he wants. As Messerschmidt highlights, “easy directors don’t make very good movies.”

Rather than making a linear biopic, Mann wanted to focus on a specific chapter in the life of Enzo Ferrari, who went from racing to building one of the world’s most famous car brands. Based on a section of Brock Yates’ book Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, the film highlights three months in 1957 when the dynamics of Enzo’s career and relationships changed.

In the portrait of a complicated character – controlled and formal in some settings yet driven, competitive and impulsive in others – Enzo (Adam Driver) is facing bankruptcy as the Ferrari factory he built with wife Laura (Penélope Cruz) is under threat. Their marriage is in turmoil following the loss of their son, Dino, and Enzo is struggling to juggle and conceal the double life he lives with lover Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley) and son Piero.

Grief and family tension are central to the narrative, as is Enzo’s drive to ensure his company’s survival in part through Ferrari emerging triumphant in the upcoming Mille Miglia – a challenging 1,000-mile race across Italy which sees him push his racing team to their limits. While driver deaths are rare in modern motor racing, the great risk taken by courageous racers in the ‘50s is well documented, and danger looms in the film’s gripping racing sequences.

Speaking in a Q&A session following a screening of Ferrari at Camerimage Film Festival, Driver – who was also an executive producer on the film – highlighted the filmmakers’ close collaboration. “Michael is very capable in every sense and he and Erik had a good rapport, especially in the racing sequences,” he said. “Michael is extremely well prepared and researched but he’s also very improvisational and impromptu… You can tell that from his movies such as Heat and Last of the Mohicans – he’s a director that’s into internal life. That’s why he’s able to make quick transitions with characters because all of his actors are filled with these rich internal lives.

“And I think he and Erik were on the same page – Michael’s very meticulous about [things like] if we can’t see [an actor’s] pupils and the blacks aren’t right then we aren’t getting [the shot] right. He’ll stop everything until he gets it because it’s all performance and character based, not so much about making a pretty picture.”

The man behind the motors

Mann initially approached Messerschmidt to team up on crime series Tokyo Vice but when dates shifted due to the pandemic, the cinematographer became unavailable. “We stayed in touch and Michael asked if I would read the script for Ferrari which he’d been working on and researching for many years,” says Messerschmidt. “It’s an extraordinary and very readable screenplay, so I devoured it and called him back immediately to say I’d love to do it.”

Having read Brock Yates’ book upon which the film is based and seen the documentary Race to Immortality (2017)about Enzo’s life, Messerschmidt came to the project with background knowledge. But an essential source of inspiration and information came in the form of Mann’s vast library filled with documents, film clips, photographs and historical records of Enzo’s life and career. As with previous productions, Mann dedicated a lengthy period to meticulous investigation, immersing himself in the world of Ferrari.

He also shared images taken on trips to Italy, in particular Emilia-Romagna in northern Italy. “All of Italy has so much aesthetic built into the place that I felt we couldn’t project too much on top of it,” says Messerschmidt. “I always try to absorb as much as possible from the environment in the beginning.” The cinematographer suggested looking at Caravaggio’s paintings and exploring the Venetian School of portraiture including the “subdued, soft top light and dark backgrounds” of painters such as Tintoretto and Titian.

“There’s so much digital trickery in modern car movies that Michael did not want to use as a reference, so we looked at earlier films such as Le Mans (1971) and went back to the basics of how we strap the camera to the car and strap the operator in the passenger seat with a stunt driver to shoot the action,” says Messerschmidt.

Designing for design’s sake was to be avoided as Mann felt it important to shoot almost entirely at real locations. As Enzo’s apartment is now an office, the interior needed to be dressed to suit but the exterior was correct. “Enzo never really ventured more than a kilometre from his home in the centre of Modena in northern Italy, so everything in his life was centred around his apartment,” says Messerschmidt. “It’s a small city and his home was near all the locations we needed to shoot – the barber shop, the opera, the family mausoleum were across the street from his house.”

In keeping with the practical filmmaking approach Mann wanted to adopt, production designer Maria Djurkovic and her team built the Ferrari factory in Modena. “It’s extraordinary there’s almost no green screen in the movie, only a few little set extensions,” adds Messerschmidt. “We were in real buildings rather than on a soundstage, and it makes a difference.”

A tale of two worlds

The visual approach was dictated by the two distinct strands of the narrative. The personal and family drama in Enzo’s life was “more restrained” and reflected by “pulled back and formal” camerawork and use of slightly wider lenses. In contrast – and echoing the polar opposites of Enzo’s character – racing sequences were frenetic, visceral and loud. “He was always very put together and formal in business and family settings but the race track is where he let loose as a character,” says Messerschmidt.

Ever since Collateral (2004), Mann has shot digital and it was deemed the best route once again, in part due to the number of multi-camera sequences required. As compact kit was a priority, the filmmakers selected Sony’s Venice 2 and Rialto 2 camera extension system. “I think we were the first film to use the Rialto 2 as Sony sent us a prototype from Japan. We had one precious Rialto 2 for the shoot,” says Messerschmidt.

Aware Mann likes to work fast and Ferrari would often demand up to seven cameras, on big exterior race sequences Messerschmidt wanted the ability to control iris position without needing an assistant to change the neutral-density filter. “The Venice 2’s internal NDs were an obvious choice because I knew I could put the lens at a 2.8 or 4 for really long lens shots and just swap NDs back and forth from the monitor,” he says.

“The camera’s dual ISO mode also meant I could light the set for the primes near wide open. And if we went with zoom or to the Skater Scope, I could adjust the ISO to get the camera where I needed without struggling to relight the set.”

Although the action took place in the air rather than on the track, Messerschmidt’s experience working with aeroplane mounts when shooting high-flying sequences in fighter pilot biopic Devotion (2022) came into play. “We did a lot of lens and vibration testing on that film and although the planes were going faster, there’s more vibration in a race car. We continued our lens and mount testing to take the additional vibration into account. We mounted several cameras to a pickup truck and drove it over extremely rugged ground to see if they would fail.”

As Messerschmidt avoids vintage lenses, finding them to be unpredictable, Panavision’s Dan Sasaki built a set of prime lenses for Devotion based on Panaspeeds. They aligned with the cinematographer’s preference for “a little spherical aberration in the highlights, especially for a period film” and were tweaked for Ferrari to have “a little less effect” as Messerschmidt knew he would mix them with zooms.

“We shot a series of tests on the lenses which are beautiful and then Dan did a similar treatment to some of the large format zooms. In the end, we needed the speed, so we ended up shooting a lot of race scenes on Super 35 (6K) and lots of long lenses. We had a fantastic Italian grip crew helping protect the kit so it all survived.”

To achieve Mann’s vision – and in line with his signature style – the P+S Technik Skater Scope compact periscope lens system was used on Steadicam, allowing the lens to get even closer when capturing emotional sequences of Enzo’s personal life. “Michael used it on Tokyo Vice and was keen to use it as a tool again for dramatic moments as it puts the lens 50cm in front of the camera,” adds Messerschmidt.

In the driving seat

Replica racing cars were built with filming in mind. Frames were designed with built-in mounting points so cameras could be quickly mounted anywhere needed, turning the vehicles into rigs.

“Michael arrived each day with a shot list outlining what he wanted to do and we would sit down and look at the best tools to cover that action. He was interested in mounting a slider on the car so the camera could move from one position to another over the course of the race,” says Messerschmidt. “We found the Hollywood Camera Slidermotorised slider and modified it so it could be wirelessly operated and put on an incline on the side of the car or behind the driver, allowing Michael to get five or six shots from one mounted position.”

Fixed mounts were also used to capture the racing action from all angles along with the Biscuit Rig drivable platform with a car body attached to capture shots in which a vehicle is controlled off-camera but looks like it is being driven by the actor.

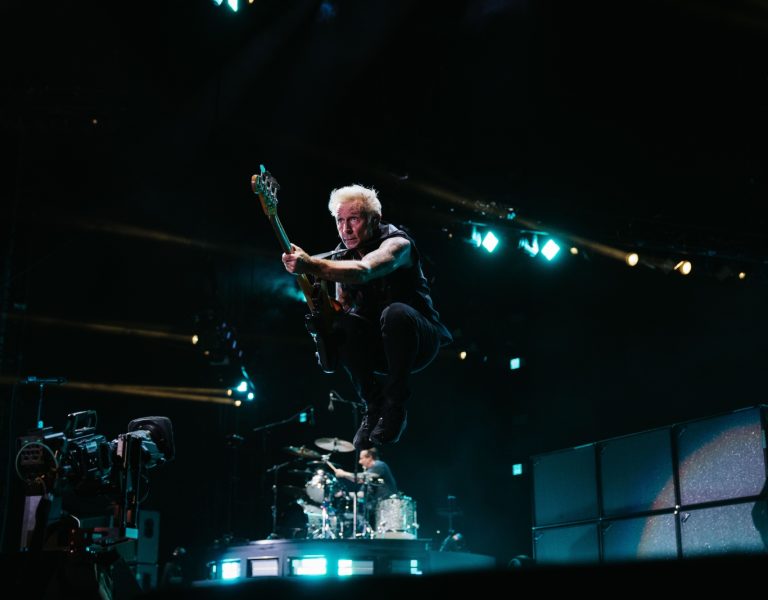

When shooting high-octane action on the race track, “the sky was the limit” for camera movement. Mann wanted to avoid traditional car photography tricks, instead putting the camera right in the driver’s seat to immerse the audience.

“The cars were going at the speed of a racing car and we had an incredible precision driving team rehearsing all the actions, including actor Patrick Dempsey who played racer Piero Taruffi,” says Messerschmidt. “We used non-stabilised Talonremote heads on the cars to get a lot of action and movement as well as hand holding the camera for some sequences. We weren’t afraid to shake the camera and we weren’t dialling it back.”

Safety was prioritised and guaranteed through testing carried out by the precision team of accomplished drivers. “It wasn’t like we were just strapping the operator to the front of the car with the actor driving – they were very specific bespoke moments with lots of safety precautions,”

adds Messerschmidt who credits much of the visual success of the film to A camera and Steadicam operator, Roberto De Angelis SOC.

“He’s a huge factor as most of the film is created by his hands,” says the DP, who would sometimes operate the third camera, with Agnieszka ‘Aga’ SzeligaACO on B cam. “We had up to six cameras in some situations. I generally don’t operate for multi-camera situations because I want to be with the director watching on the monitor,” says Messerschmidt. “Michael is also heavily involved in the camera direction, and sometimes operates the camera himself.”

Sweeping shots of the race circuits and winding Mille Miglia route were captured from an elevated viewpoint by Messerschmidt’s previous collaborator, drone aerial DP Davis DeLillo and drone pilot/specialist David Mariottini, with camera operator De Angelis also shooting some handheld sequences from a helicopter. “The drone team was with us for a long time and we mostly needed speed for those sequences,” says Messerschmidt. “Davis used a DJI Inspire 3 as well as a heavy lifter drone working as an antenna repeater for the wireless video which we used for plate work.”

Communicating through colour

The colour red is only introduced when the iconic Ferrari cars appear. When determining the wider colour palette, Messerschmidt was influenced by the amber hues that already exist in Modena. “Many of the buildings are an orange colour, so when the light hits the houses and windows these brilliant yellows, burnt umber, and honey colours are created. That’s what Italian summer looks like to me in terms of colour.”

DIT Calvin Reibman and Messerschmidt built a number of LUTs for the film including one with an extreme yellow highlight and a lot of green in the shadows. As Mann was impressed by the dailies, that LUT was sent to Stefan Sonnenfeld, senior colourist at Company 3, so the grade would be in keeping with that look. “Michael was very involved in every step through to the grade which was more a process of exposure correction because of changing lighting conditions than it was about creating the look,” says Messerschmidt.”

In keeping with the work of the Italian painters that influenced the overall aesthetic, Messerschmidt wanted to work predominantly with top light and soft front light. “I’d go to a location with gaffer Janosch Voss and rigging gaffer Thorsten Kosellek – who I adore working with – and we’d generally know the blocking and camera position, and would throw some units up in the air. I like to give myself five or six options as it can be dangerous if you light for one specific set of blocking because if the actors arrive in the morning, run the scene and the blocking shifts, you can’t respond.”

Messerschmidt and the lighting crew used mainly LED fixtures including LiteGear LiteMats, Astera Titan Tubes and Creamsource Vortexes. The Rodlight- an LED inflatable tube Voss brought from Germany – also played a significant role for sequences such as the bank and Ferrari apartment interiors. On soundstage the crew built a replication of what the interiors of the opera house and Ferrari apartment might look like so Messerschmidt could demonstrate the top light he planned to use to Mann. The LUT was also applied at this stage and refined on a case-by-case basis to align with what Mann felt was most suitable for each scene and space.

While a simple lighting set-up was adopted for daytime scenes and many practicals were used, Messerschmidt admits he “had a lot of anxiety” about a nighttime scene when the cars leave the start line on the Mille Miglia route. “We had condors there because I was worried about lighting the background, but in the end, we turned them all off and just used the car headlights because it looked more realistic. I didn’t need as much speed as I expected as working with the Venice and primes meant we had plenty of light.”

Immersed in the film

A thorough study of racing from the period – which was broadcast and well documented – was called for when planning how best to capture a devastating crash scene. “We looked at 8mm and 16mm kinescope newsreel recordings and Michael showed us footage of the famous 1955 Le Mans racing disaster that killed many people. He said it was an important reference because he wanted to see the crash almost completely objectively, like it just happens in front of the camera, and you’re just left with that. That’s very much the feeling you get when you watch this reference clip,” says Messerschmidt.

The principal crash sequence was captured with nine cameras. Following thorough testing, a remote-driven vehicle with a cannon inside was driven along the track, before hitting a marker and tumbling. “During testing a trebuchet flung cars of different weights at various speeds to get it to tumble in a way Michael was happy with,” says Messerschmidt. “On the day we only had one car, so there was a lot of pressure on us.”

Bringing such scenes to life authentically and safely was a collective effort which saw individuals such as stunt coordinator Robert Nagle heavily involved in the racing choreography. The cars were recreated with cooperation from the Ferrari factory to ensure they were historically accurate and correctly represented the brand. Designs for the replica cars – which needed to safely travel at around 140mph – were produced based on 3D lidar scans of the real cars.

Although Mann wanted to minimise the use of VFX in general and for the pivotal crash scene, an array camera was required to shoot photogrammetry plates for the visual effects team to use. A black-and-white sequence of Enzo racing that opens the film – a late addition from Mann – also required Driver to be shot in a car using mounted cameras before visual effects comped him into real race footage, and grain and gate weave were added.

In a production packed with complex camera movements, fast-paced races and elaborate technical set-ups, Messerschmidt considers an emotional confrontation between Enzo and Laura at a pivotal point of their relationship’s deterioration to be as powerful as the high-octane action that takes place on the race track. “We blocked it on the day, it was very fluid and Michael wanted them to be free. In that scene, one of my favourite shots is Penélope standing next to the lamp – it’s very simple yet powerful. The whole sequence stands out as one of the moments for me as a cinematographer when I watched a performance in real time and it really affected me. Watching her and Adam perform that scene, I felt like I was taken out of the filmmaking process and into the film.”