AN AMERICAN TALE

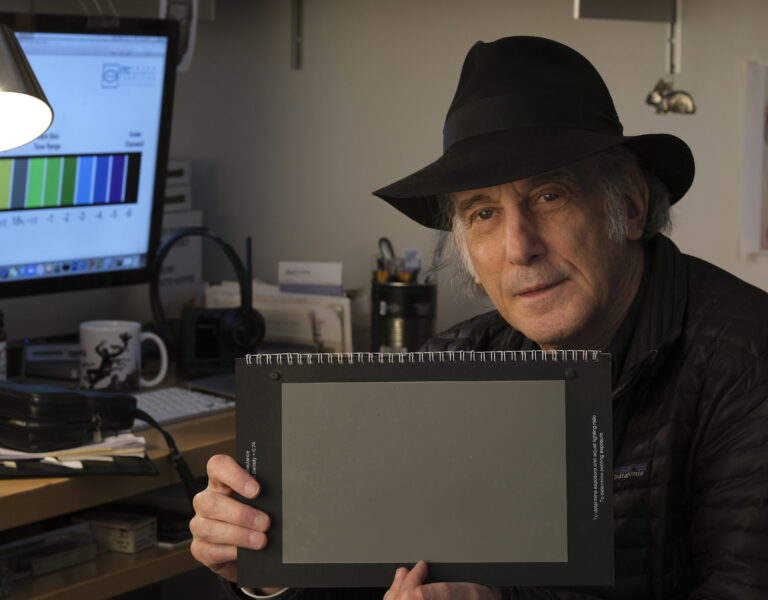

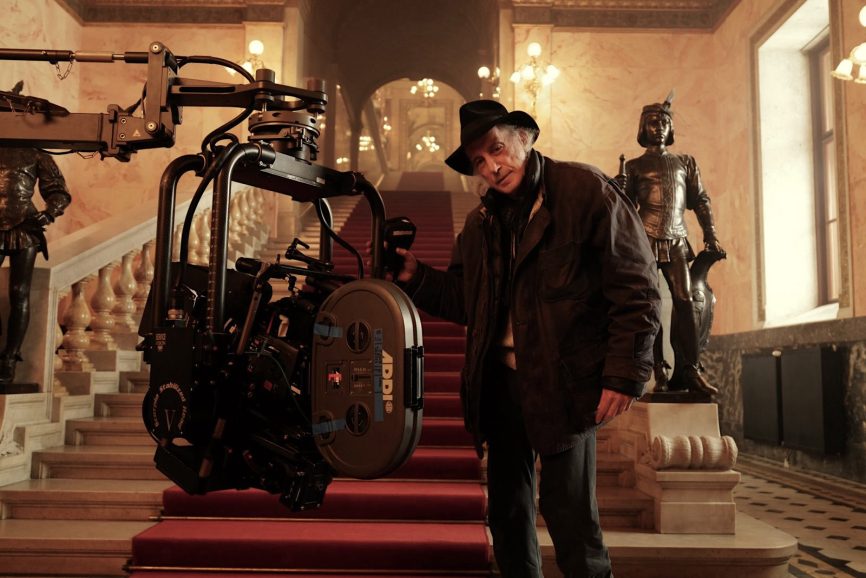

Three-time Oscar nominated and recipient of the 2024 Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award, Ed Lachman ASC talks to British Cinematographer about an extraordinary career.

If filmmaking is a never-ending education, as Ed Lachman ASC believes, then he is a professor. His extraordinary career overlaps and intersects with so many filmmaking greats – and he has extended the artform with defining work himself. When Lachman mentions Robert Altman, Bernado Bertolucci, Paul Schrader, Nic Roeg, Werner Herzog, Dennis Hopper, Wim Wenders or Steven Soderbergh, these are filmmakers he has worked with. For many DPs, Vittorio Storaro, Sven Nykvist and Robby Müller are three of the greatest cinematographers to have lived. Lachman learned at their feet.

“The greatest film school I could have ever gone to was the opportunity to work with Sven, Robby and Vittorio,” Lachman says. When he quotes Jean-Luc Godard, know that the revolutionary auteur invited Lachman to collaborate with him (on Passion, 1982).

“For Godard, images were always about the idea behind the image, rather than just some abstract aesthetic concept,” he says. “Once you can start thinking about what they represent, you will create images that transcend their own clichés.”

All those filmmakers share an indie pedigree and they all either helped birth or were influenced by groundbreaking European film-art movements of the 1960s and ‘70s.

What was it that attracted a New York native to seek out artists across the Atlantic? The same approach to storytelling that kept him within their orbit. “I was studying painting and art history at Harvard and Ohio University and discovered Dadaists and German expressionism which dealt with the psychology of the subject matter to express an idea,” Lachman relates. “It was a natural progression for me to want to look to Europe.”

Artistic license

In the wake of neorealists Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica, young Turks like Bertolucci, Herzog and Wenders proved inspirational in their freedom to explore ideas, styles and period.

Lachman says, “Hollywood had a system of how to create images to be used in the editing room. That’s not a pejorative. It’s just that that was the form. But in Europe each filmmaker found their own language to tell the stories that were personal to them.”

By extension, the cinematographer and director were co-authors of the film in a way that American cinema at that time was not. “For the directors I was attracted to filmmaking was more of a complete process inclusive of writing, shooting and editing. It wasn’t compartmentalised like making a car on an assembly line.”

In the early 1970s American independent film was about to have its renaissance but Lachman went to the source. “I really learned about American Cinema through the French Nouvelle Vague because [fabled film journal] Cahiers du Cinéma was referencing Sam Fuller, Nicholas Ray and other American auteur voices.” Lachman worked with on Ray’s final film Lightning Over Water in 1980 with co-director Wenders.

Student days

During college Lachman made films in Super 8 and 16mm—”simple portraits of people I met. As I was shooting them, I was always thinking about various artists and their different schools of painting.”

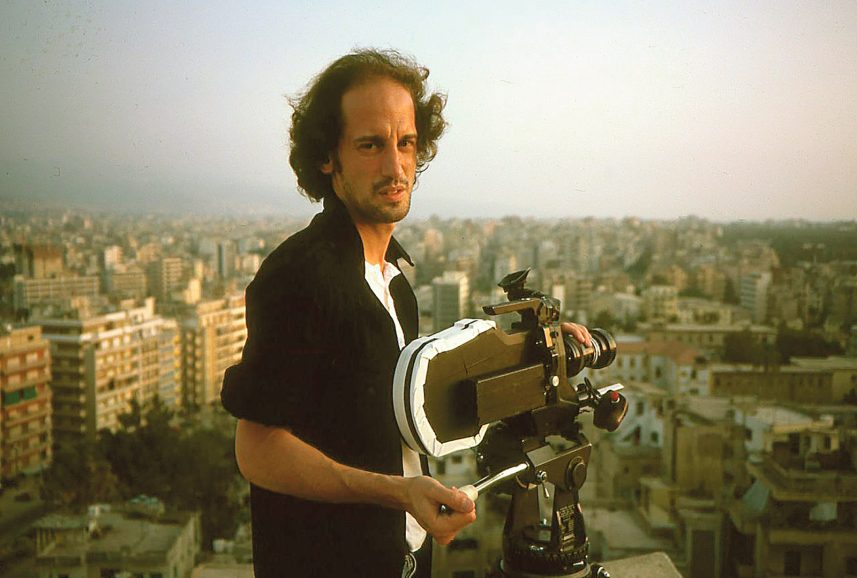

In 1972, while editing his post-graduate film (about the therapeutic community for drug addicts Odyssey House) at a rented editing room at the Maysles Brothers’ studio, he impressed the documentarians enough to get invited to do sound, run their office, and shoot second camera for them. Lachman attributes the experience they gave him of treating even narrative films as docs; “No performances are exactly the same. ”Filmmakers like Herzog and Wenders whose work has constantly blurred the boundaries between fiction and documentary agreed. Herzog become friends after meeting at a screening of the director’s 1968 film Signs of Life in Berlin. A little later “without looking at a frame of my films” Herzog hired Lachman to work alongside German DP Thomas Mauch. In short succession he worked on Herzog’s How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1975), Stroszek (1976), La Soufrière (1976), and Huie’s Sermon (1980).

He is indebted to Herzog for an introduction to Wenders “a librarian of imagery” through whom Lachman got to meet Müller. “I befriended Robby and his entire crew when I helped them on American Friend (1976) and they ended up staying with me in my New York loft – where we also shot the hospital scene.” Lachman lives there still. “It was an honour to operate for Robby but more importantly to learn and to be inspired by him,” he says. He operated for Müller on They All Laughed (1981) directed by Peter Bogdanovich, and Body Rock (1984). He shot for Wenders the doc Tokyo-Ga about Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu, and Lightning Over Water, with Nick Ray co-directing the film.

The Italian job

When Bertolucci came to New York to shoot La Luna in 1979 “he was generous enough to ask me to assist him and Vittorio.” Years previously, Lachman had done his university dissertation on Bertolucci’s 1964 drama Prima della rivoluzione, with his acknowledgement not fully understanding the modern Italian politics of the film. “It’s about a young man who couldn’t resolve his leftist beliefs and I didn’t understand the social context of bourgeois middle class or what that conflict was totally about. I wasn’t part of that world.”

He has connected to films like Mira Nair’s interracial romance Mississippi Masala (1991), Steven Soderbergh’s whistleblower drama Erin Brockovich (2000), and another true-life environmental cover-up in Dark Waters (2019), and the black-and-white depiction of General Pinochet and Margaret Thatcher as vampires in Pablo Larraín’s satire El Conde (2023), all embody a social and political engagement. El Conde also won Lachman his third Oscar nomination.

“I think all films are political. As it happens, I work with filmmakers that have the intellect and interest to look at society through their art. It’s just more interesting to work with people that are questioning the values that surround us and who use their work to express their ideas with it.”

Euro vision

A student of cultural history he notes that when social economic conditions are uprooted new artistic movements emerge as with New German Cinema of the ‘70s, a response to the stagnation of the West German film industry and the social and political transformations occurring in postwar Germany. Does that mean there might be a cultural eruption in response to the rise of the far right? “There will always be a reaction when the economic and social conditions are there,” Lachman says. “If you look at where compelling films are being made now, that seem to have a conscience, you can see interesting work from Latin America, Iran, India, and the Far East.”

While he is drawn to the political subtext of projects he is equally taken by the way directors choose to visualise those stories. Larraín, for example, presented Chile’s dark history as a gothic noir featuring vampires “a mash-up I felt impelled to help create.” He says, “Some directors have a strong visual sense and some don’t but it’s the ones with the strongest visuals I’ve been lucky enough to work with. I plug into their world and try to implement something of myself.”

Making the cut

Lachman’s commercial breakthrough as solo cinematographer was for Susan Seidelman’s Desperately Seeking Susan (1985) introducing German Expressionism into Madonna’s feature debut. “1980s New York was economically and socially depressed as it was being gentrified. The housing was rough. So, I thought about a heightened reality that was foreboding and dangerous. I was influenced by how Adam Holender ASC had presented an impression of the city in Midnight Cowboy (1969) and thought the feeling of the downtown streets could be a stylised German Expressionist vernacular for Madonna while Rosanna Arquette’s world was a pastel mundane suburban environment.”

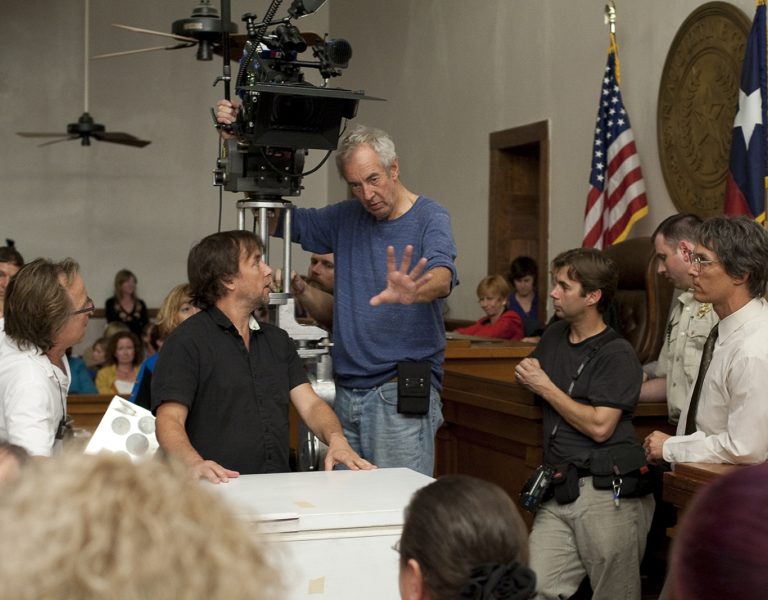

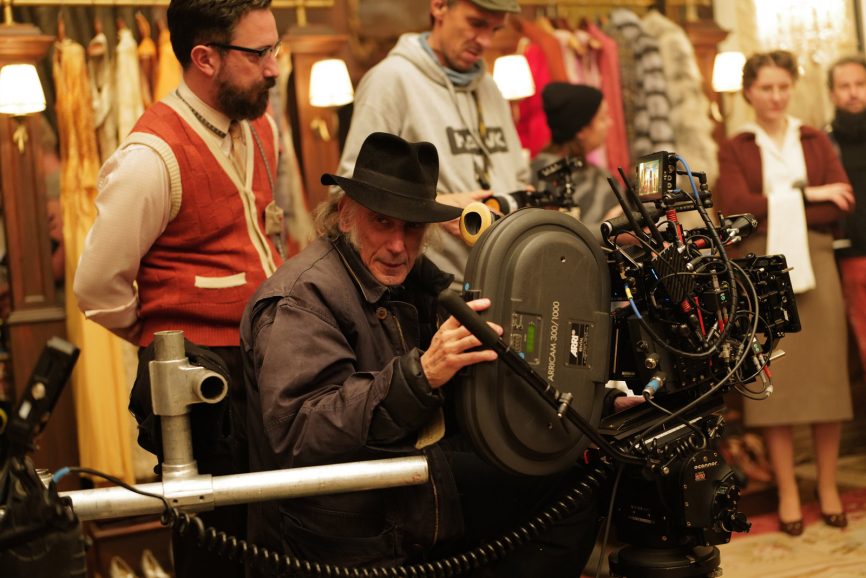

He says, “A cinematographer is like another actor. You’re giving a performance, to a degree. You’re reacting to what’s in front of you. That’s why I think a lot of directors want to be on the camera because they’re the first audience. I certainly like to be operating because I like the immediacy of the moment in telling a story visually.”

Above anything, though, it’s the passion of the director that excites Lachman. “Their passion in why they want to tell this story and also their passion for finding a visual language to tell the story. It’s not about close-up, medium, long shot and coverage of dialogue. “When I read the script, I develop many visual ideas of how to approach a story. At home I have a library of hundreds of photography and art books filled with images that I find inspiring. Each painter has their own aesthetic about why and what they paint. It should be the same criteria for a film director.”

Oscar-nominated for his camera work on Far From Heaven and Carol, Lachman says Haynes is one of the most prepared directors. “He has an extensive shot list but is always open to responding to the immediacy of the moment. When we research a film, he creates a ‘look-book’ illustrating the cultural history, politics, demographics, art, fashion as well as the cinematic language of the film’s period that provides the emotional structure of the film for me.”

Lachman has been in the director’s chair himself on projects including Ken Park (2002) which he co-directed with Larry Clark from a Harmony Korine script.

“There are certain projects I like to direct because I feel I have more control over the image but I’m very happy to be just a cinematographer. Then I can just be in that world and not have to deal with everybody else’s problems. Plus, I have a crew to help me. When you’re a director, everybody comes to you to solve their problems.”

Each craft also requires a different mentality he says. “Put it this way, cinematographers may know how to tell the story but do they have a story to tell? That to me is the difference between a director and a cinematographer. Directors must have a burning passion to tell the story, which can be told in many different ways. As a cinematographer, I feel my job is to come up with solutions for the director in how to tell their story.”

Songs for Drella, a 1990 concert film Lachman directed and photographed with Lou Reed and John Cale, was an attempt to immerse the viewer in their performance. “When I first met Lou he said, ‘I don’t want any fucking camera between me and the audience. They paid for the show and want to see our performance.’ I went home wondering how I could possibly shoot the concert without cameras obstructing the audience. I came back the next day and proposed to shoot their rehearsals for two days without an audience with just my camera on stage creating an intimacy of the camera’s movements to the music, and one day with the audience and cameras off stage. They agreed. Lou’s challenge to me resulted in the viewer being closer and creating the intimacy with Lou and John’s performance that I never would have had if I only shot the actual concert.”

Looking ahead

In his 78th year Lachman is still going strong, having completed a Maria Callas project with Larrain. At MoMa he’s helped curate a retrospective of photographer Robert Frank, an influential artist and a friend. “He imbued images with his own experience and how one can impart his poetry and personal vision in images. Frank showed us how to instil realistic or found images with the experience and subjectivity of the photographer.”

Lachman is not concerned that the sugar rush of AI and virtual cine technologies will damage the future of the craft. “Film has the ability for us to experience what is seen and hidden at the same time. It can reveal the depth of our own reality and open us to a fuller sense of ourselves. Cinema is little over a century old it will always evolve new visual grammar as filmmakers explore new languages to tell their stories. It doesn’t matter if we do it on 8K, Super 8, or an iPhone. We will always need filmmakers to understand the world that we are trying to live in and tell stories for the ways it connects all of us.”