FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL

Eben Bolter BSC enjoyed a year of creative adventure in Canada when he took on his dream job helping adapt beloved video game The Last of Us for a television audience. The British cinematographer shares his approach to lensing three episodes of varying tone and narrative.

The television adaptation of The Last of Us has thrilled fans of the game one which it is based as well as viewers venturing into the immersive world for the first time. Creating the hit nine-part series also had a profound impact on those translating it for a TV audience including Eben Bolter BSC (Night Teeth, The Girl Before) whose views on the cinematographer’s role and the type of DP he wants to be were clarified when lensing three episodes.

“I don’t want to be an ‘It’s all about me, the lighting is everything, everyone get out of my way’ cinematographer. I want to be empathetic and make the best production possible by playing my part in the visual storytelling, while not obstructing it,” he says. “It’s also important to realise when it’s best to use an expensive and complicated lighting rig and when you should just use the sun and let the performers do their thing.”

Based on the blockbuster action-adventure survival video game created by Naughty Dog for PlayStation 3, the HBO series is set in a post-apocalyptic world ravaged by humans infected by a parasitic fungus that transforms them into ferocious mutant beings. Like the award-winning game, the production follows survivors Joel (Pedro Pascal) and Ellie (Bella Ramsey), the 14-year-old who may hold the secret to humanity’s continued existence. As they embark on their mission across America, braving a battleground where danger lurks around every corner, Joel strives to protect Ellie from harm.

The acclaimed game – a shining example of world building, beautifully crafted human stories, and intricate character development – offered the perfect source material for Emmy award-winning creator of Chernobyl, Craig Mazin, and director and writer of the game and co-president of video game developer Naughty Dog, Neil Druckmann, to use for the television adaptation.

The thrilling task of lensing the carefully constructed world was shared by cinematographers Bolter (episode three, four, five and additional photography for several other episodes); Ksenia Sereda RGC (episode one, two, seven); Nadim Carlsen DFF (episode eight, nine); and Christine A. Maier BVK ACC (episode six). Each of the nine episodes offered the cinematographers endless creative possibilities to explore and had the power to be their own standalone movie.

The year of creative exploration in Canada British cinematographer Bolter enjoyed when he took on his “dream job”, saw him lense the intimate “Long, Long Time” (episode three) revolving around the love story between Bill (Nick Offerman) and Frank (Murray Bartlett) and requiring a more delicate touch. In contrast, “Please Hold My Hand” (episode five) and “Endure and Survive” (episode five) which he also worked on were larger in scale and demanded different techniques, in particular when capturing a battle sequence unfolding in a cul-de-sac.

Before joining the production, Bolter was already a fan of the game, having played it extensively when it was released in 2013, immediately drawn to the world and characters. “It was the first game I played that my wife insisted on watching with me. It made me cry. It made her cry,” he says. “The game played out in this incredible world accompanied by a beautiful score and scenes that felt so cinematic. It just had this whole aura to it and was almost its own genre. Essentially, it’s about love, human beings, and survival. The zombies are just obstacles in the way.”

If a television or film adaptation was ever planned, Bolter was eager to be part of it. “When Chernobyl came out – the series created by Craig Mazin – it was the best thing I’d seen in a long time, and I wanted to meet for whatever Craig did next,” he says. “So, when the two things came together – Craig Mazin making The Last of Us for HBO – my dream job had been announced.”

Bolter contacted his agent, emphasising his passion for the project. She got him in front of the producers, highlighting his previous work with HBO before at the same budget level, and his adoration of the game. “They were going to bring in a DP and director for each episode, almost treating it like a movie,” he explains. “But they saw how keen I was in a two-hour interview where ideas were bounced back and forth and all the references married up, so they brought me on early before my directors.”

Cinematic at its core

Bolter could see the concept of the game was fundamentally cinematic – a world in which mankind’s touch has been frozen in time for 20 years, technology has stopped, and nature has taken over again. “It’s a beautiful mix of post-apocalyptic, broken humanity, and nature thriving outside the window. You’ve got 20 years of shopping malls left to decay while beautiful vines, trees and wildlife make their way in.”

The ambition for Bolter and the cinematographers lensing the other episodes was interpreting that concept for the medium of television. Rather than looking at what makes a series feel like The Last of Us, they carried out a subtractive process of exploring what it should not be. “It’s not glossy and slick, so anytime anything felt overly lit, used traditional camera moves, or felt too Hollywood cinematic we’d change it,” he says. “We wanted to ground things, see them through a documentary style camera, which meant a lot of handheld work.”

Tonal comparisons could be made to the tangible grittiness and lack of lighting in Children of Men (2006), but the film differs to the series as it uses wide-angle lenses and Steadicam shots. Large-scale battle sequences from films such as Saving Private Ryan (1998) were also useful reference material, in particular Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kamiński’s use of perspective in a sequence of a sniper in a tower.

With the audience viewing the environments and scenarios through a cinematic lens, it was decided lighting would be led by nature. “Suspending disbelief and making it feel like a real story about real people in a real world was possible by not veering too far into hyperreal cinematic territory,” Bolter adds.

Adapting the much-loved video game was a sizeable responsibility, but for Bolter much of that pressure was self-inflicted as he “cared so much about the story and characters”, putting everything he had into it. “It wasn’t a job; you’re not counting the minutes until you wrap every day. It’s about how you make the adaptation the best it could possibly be.”

Bolter and the other members of the crew endeavoured to do the exceptional scripts justice. Reading Bill and Frank’s love story unfold in episode three, it was apparent “the script was mind blowing – the subtleties of their performances, the songs, it was all there.” The task for Bolter and episode three ’s director, Peter Hoar, was then “making it as great as it could be” on screen.

Understanding of the source material was detailed throughout the team. B camera dolly grip, Kyle Robson – another “huge Last of Us fan” – instantly spotted any changes to lines of dialogue. “In terms of the game’s fans, I’m one of them, so I could feel when things from the game were not quite working in the live action,” says Bolter. “But we weren’t slaves to the source material, so if anything changed, it was done for the better and for good reason.”

Working with show runners Druckmann and Mazin was a thrilling and inspiring experience. Mazin, who led the adaptation of the series and was the main writer, was on set every day. “He was across every shot and set-up,” says Bolter. “There was a high expectation which brought the best out of people and kept everything elevated. Neil sometimes needed to be in Alberta as he also has a video game studio to run, so sometimes he was in contact remotely for some of the bigger decisions.”

During prep for each episode, Druckmann talked through aspects such as how characters would behave, and the environments based on research conducted when creating the game. “He has 10 years of living in this game world and shared so much knowledge,” says Bolter. “Between Neil and Craig everything was covered, leaving little discovered or figured out when you turn up on the day.”

In tone meetings, Mazin talked through the script from beginning to end – not just the surface level but what is really happening underneath and the subtle deeper meaning of every scene. “They were some of the most fascinating filmmaking experiences I’ve had,” says Bolter. “So much is there in little kernels in the scripts but when it’s solidified by the writer it instantly orientates the scene, giving you a head start on how to shoot it.”

Along with the scripts, Bolter was sent a 130-page show bible PDF created by Mazin and Druckmann outlining the world of The Last of Us, characters, and visual approach. Rather than discussing in depth with the other cinematographers, they were each left to interpret Mazin and Druckmann’s vision as individuals. “It was a bit like the world of Star Wars – each movie can look different while being from the same group. We were given flexibility, but always needed to deliver the same world. I think that’s why we got the job – as cinematographers we each demonstrated we understood what that world was,” says Bolter.

“Ksenia Sereda did an incredible job on the first episode setting up the camera, lenses, and aspect ratio. Everything else was to do with world building and using Craig and Neil’s bible, so the directors and I felt liberated to interpret it in our own way.”

While each episode stood largely on its own and conversations between cinematographers were rare, Bolter had more in-depth discussions with Christine A. Maier when he shot additional photography for episode six which she lensed. “I wanted to get into Christine’s head and give her exactly what she wanted,” he says. “And when I covered a couple days for Ksenia on episode seven I did my best impression of her work. We all have our own subtleties, like handwriting, you can’t get away from that, but the world building and Craig being there as a showrunner gave it that through line, so it feels consistent whilst allowing us to express ourselves episode by episode.”

Emotional reaction

Bolter did not feel the need to change the ARRI Alexa Mini and Cooke S4s selected by Sereda for her episodes, believing the 20-year-old lenses and 10-year-old camera lend themselves to a world frozen in time for two decades. “I’ve worked almost exclusively with ARRI cameras for a long time, and they never let me down,” he says. “I liked using Super 35 on this occasion instead of large format to have more depth of field. The S4s were well suited as they aren’t funky or weird lenses – they’re naturalistic, simple and deliver good contrast and colour.

“ARRI Rental were incredible, as always. Nothing’s ever a problem and if we needed four additional cameras last minute, they’d pulled everything together instantly.” For a sniper sequence, they required incredibly long lenses to experiment with putting a rifle scope in front of a 500mm and a 700mm lens. By lunchtime they had been delivered to the set. As this experimentation demonstrated that a practical scope in front of the lens looked fake, they shot the sequence clean before VFX created the scoping elements.

The new ARRI Full-Spectrum ND filters – the cleanest ND filters Bolter has used – were ideal for the cinematographer who admits he is “very fussy when it comes to colour.” He used soft edge ND filters for certain shots including those featuring expansive skies such as when Ellie and Joel drive away from a gas station with a big beautiful stormy Calgary sky in the background. An ND Soft Edge 3 was in the bottom of frame and an ND 9 in the top of frame, leaving the truck in the lower third clean, and the sky pulled right down.

Rather than working with a show LUT, Bolter and DIT Dylan Metcalfe created a CDL colour tweak to slightly warm the image, adding a tiny amount of green and contrast, so the dailies were closer to the final product. “I wanted to use the full spectrum of warmth and coldness to tell Bill and Frank’s love story in episode three, and I knew we would use a 35mm Kodak emulation of sorts, but it wasn’t anything heavy,” he adds.

After collaborating with cinematographer Sereda, helping develop the look for the first episode, Company 3’s senior colourist Stephen Nakamura worked with her and the season’s other cinematographers Bolter, Carlsen, and Maier on their episodes.

“Ksenia wanted to really lean into some heavy looks. When it’s warm, it’s really warm and the same when it’s cold. If a source is supposed to be sodium vapour, the picture goes heavily in that direction,” says Nakamura. “She and the other cinematographers were not afraid of taking this show to extremes you don’t see on a lot of other shows. I can colour each scene based on my emotional reaction to what’s happening.”

Bolter carried out the final grade of his episodes virtually on Zoom with Nakamura, who Bolter commends for his “excellent sensibilities”. The grade was “very gentle and often a case of less is more. Occasionally we’d shaped things a little due to the naturalistic approach to shooting scenes such as those with Bill and Frank and not wanting to get in the way of their performances.”

Organic movement

When working on a largely handheld series such as The Last of Us, Bolter avoids feeling the operator’s presence, “wanting handheld to be attached to the characters, and not feel like there’s a separate person in the room or like the camera is walking towards a character.” He wants the operator to move their feet when the actors move their feet, “so you’re hiding that movement. It’s always a dance.”

To achieve the required organic movement Bolter, who does not operate, brought on board LA-based Neal Bryant as A camera operator and Steadicam operator, having worked with him on 2021’s Night Teeth. Bryant used a ZeeGee three-axis cradle device on top of the Steadicam arm to create a handheld camera.

“It removes the shoulder bounce I don’t like and allows you to set a non-arbitrary height so Neal could operate handheld from below his waist or above his head and the operating looks the same,” says Bolter. “I can’t stand it when it feels like a tall operator is looking down. Neal has such excellent instincts and I just fell in love with the ZeeGee. While the ZeeGee wasn’t used for episodes where the cinematographers operated, we lived on it for 99% of the shots in my episodes. By the end my B and C camera operators were using it, even on long lenses.”

Several times per episode Bolter and Bryant moved from handheld to a slider, dolly or a crane shot, always led by the story. The final shot of episode three which pulls back through the window of Bill and Frank’s bedroom was a crane shot because it “felt like it needed to be perfect because it’s a storytelling cinematic final shot that wouldn’t suit handheld.”

If C camera operator Jarrett Craig could not fit into rooms being captured, such as in episode three, he and his team were sent to shoot Bill’s town, finding interesting shots of the sun through the trees, a flag blowing in the wind. “Some things needed to be shot five times as the art department gradually aged elements of the set. Collecting those additional pieces was a huge job,” says Bolter.

In episode four when Ellie and Joel set off on their road trip across America, the driving sequence was captured by the second unit. Bolter storyboarded shots of bridges and roadsides and sent the second unit on a mission to capture them. The cinematographer’s approach is “to give them a specific shot, but also liberate them to be creative, see what’s happening on the day and get something better.”

He credits the “spectacular” team, including A camera 1st AC Luke Towers who was on the job for 240 days and never produced a soft shot. “I got to come and go and did 80 days of shooting over the 240 days, but crew such as Luke and DIT Dylan, did every day. I’d come back in well rested, and they still had energy and were ready to go. Their stamina and the quality they maintained was incredible.”

He likens the crew to “an army of Last of Us lovers who realised how great this could be. Every episode felt like a Sundance movie, it didn’t feel like a job or just another episode of TV.”

Lensing a love story

The series united Bolter with British directors Peter Hoar (episode three) and Jeremy Webb (episode four and five) for the first time, enjoying a “brilliant creative collaboration” and ample prep time which is rare for television. The cinematographer reveled in the challenge of lensing vastly different episodes – three focusing on a central love story playing out over 20 years in contrast to episode five which features an action-packed battle sequence complete with burning houses.

Bolter and Hoar were determined for their screen interpretation of the third episode to live up to the incredible script, so they did page turn after page turn, extensive shot listing, and discussed every aspect of the locations visited, leaving nothing to chance. “The episode revolves around a middle-aged gay love story, and Peter’s perspective and insight as a gay man into those stories, interpreting those characters and having worked on It’s a Sin was crucial for me to listen to and understand,” says Bolter. “I came into this very much as an ally and was just trying to present a love story in as honest and truthful a way as possible.”

The environment created on set was also vital to the success of the calmer, more intimate story focused on the couple’s relationship – a departure from much of the series’ zombie post-apocalyptic battleground. While Nick Offerman is not a gay man, his character Bill is, so part of Hoar’s role as director was guiding Offerman and creating a space in which to flourish and feel confident. “The environment we created on set was intimate, generous, open and warm, and Peter played a huge part in that,” adds Bolter.

The intimacy coordinators’ approach was also based around openness and truth through a collaborative and gentle process. “It’s crazy to think we didn’t really have that role in the past. It’s like doing stunts without a stunt person,” says Bolter. “You need someone to be the through line so everyone’s safe, comfortable, and happy.”

The 45-minute tale of a blossoming relationship provided opportunities to play with weather and tonality while making the 23-day shoot feel like it was playing out over two decades. “It’s mostly a happy love story and very romantic, so often it was about restraint and picking key moments to really visually enjoy this and let it be warm and loving, but also find moments to be colder and embrace the seasons.”

As the world of The Last of Us is the result of 20 years of decay and natural growth, it was not possible to walk into any location and just shoot. Every aspect had to be modified or built and demanded detailed prep. And as the road trip tale follows Joel and Ellie on the move, they were forever stepping onto new sets. “The job for the art department and location team was colossal. Every scene was a new set, which is so rare,” says Bolter. “Almost every interior is a set build and we had three full studios – the equivalent of Pinewood Leavesden and Elstree – full of just The Last of Us.”

When identifying what was needed to make each place visited along the way authentic, the team knew Bill’s town in episode three needed a small quaint location that looks like outer Massachusetts, New England, but could be fenced off and aged. The solution was an abandoned lot in a forest in rural Alberta, where the art department built the town’s houses and gradually aged the location three years at a time as the story jumps ahead.

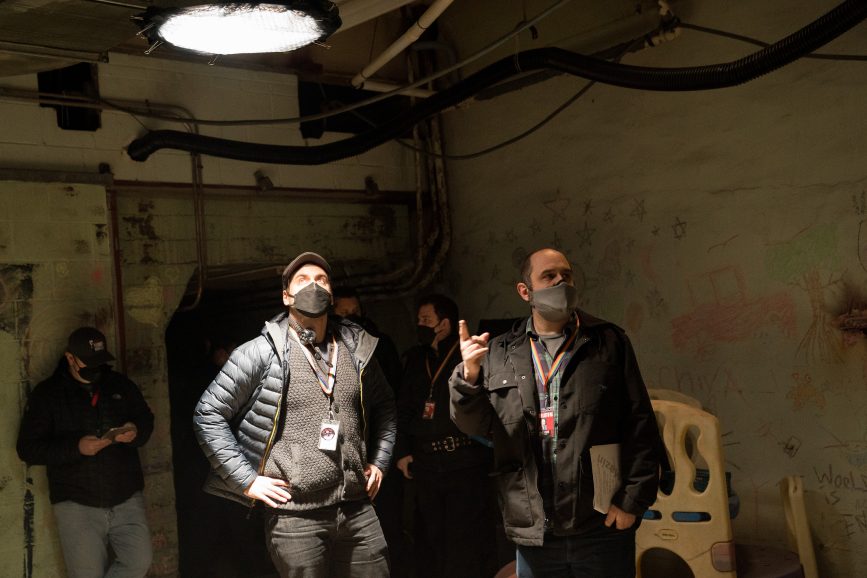

All interiors for the episode were built on a soundstage at Calgary Film Centre and Rocky Mountain Studios which the art department made feel like real locations. Adopting a diegetic lighting approach, Bolter always considered how to light each room when examining early designs for the spaces. “Where are the cast likely to be? Are they going to be holding a lamp? Do I have enough windows? Do I need a hole in the ceiling? You must have those conversations really early,” he says.

Framing was always story led and driven by the character’s perspective and examining aspects such as how close the camera is to a character and how shallow the focus is. “It was always a psychological approach, and we never just did something because it looked good,” says Bolter. “This job made me think about the role of a cinematographer for the greater good of a project. Much of the time, our role is simplified into how good something looks, when, in my opinion, there’s no point being obstructive to the overall process of filmmaking to make a shot look better.”

Bolter uses the example of Bill and Frank at the piano as a sequence which is all about performance. “We knew they were going to sing a song, kiss, share all these moments, and we had to create an environment where they were free to perform.”

He wanted the scene to be cross shot – one camera on Frank and the other on Bill and a two shot in the middle – letting it play out in one long take, capturing everything. “That gave us a much better scene than if we’d shot Frank and taken 45 minutes lighting it perfectly and turned around and done the same capturing Bill,” he says. “The Last of Us was about really considering how we make the overall great, and sometimes that means you have to light a huge moonlit walk and talk, and other times you’ll cross shoot with minimal lighting, and just let the performances be great.”

As so much of the overarching story revolves around nature, Bolter identified scenes where he felt he “could get away with using the real sun.” He knew the “brilliant actors probably wouldn’t need many takes” for the two-page scene in episode three when Bill and Frank pick strawberries, so he and Hoar decided where to put the strawberries based on where the sun was at magic hour. “We also identified we could go really big and romantic for the scene, so I wanted a bit more atmosphere in the air. Instead of smoke, we used feathers SFX shredded and sent them up into the sky using big fans which on camera looks like pollen on a summer’s evening.”

When episode three departs from the love story and raiders attack Bill and Frank’s town, Bolter knew he did not want to create moonlight, instead opting for fire to produce the feeling that “hell had descended upon their home”. The cinematographer also wanted the scene to connect the exterior of Bill and Frank’s town built in a forest to the soundstage interiors. “But we didn’t want to force a cut from Frank coming downstairs, getting the gun, running outside and coming back inside with Bill, so the art department dressed a corner of that room and the front door, so we could come downstairs, go into the room, look out the window and see the real fire, get the gun, follow him outside, go all the way over to Bill. It’s all real and in camera, playing that whole scene out in a room with just two corners.”

SFX was also integral to the power of that scene. Inspired by the rain he embraced when shooting a burning caravan in feature Chicken (2015), Bolter mixed fire and water again but this time using rain machines. “SFX did a great job making that rain work when we were running handheld through all that chaos,” he says. “I don’t think you can tell it is rain towers.”

Continuing the journey

As the road trip progresses, Bolter set out to create a different feel in the Kansas City featuring in episode four and five through subtle nighttime lighting techniques and changing the colour of the streetlights to a more yellowy green, sickly sodium colour compared to the earlier episodes.

A sequence in episode five sees Joel and Ellie walk through a cul-de-sac in the moonlight, using torches to avoid being seen required a huge expanse for a walk and talk and then an action scene where houses would be blown up, and gunfire and fire would be incorporated. “We couldn’t shoot that in a real town and blow up houses, so we built the 2,500 by 1,500-foot cul-de-sac on a backlot at Rocky Mountain Studios – an impressive achievement from the art department,” says Bolter.

During prep production designer John Paino, Bolter and director Jeremy Webb talked through each set. “So much building work was needed as they had to deliver 19 houses for episode five, lay down tarmac on what was a field, and ensure it was correct because you don’t want to block the scene and realise you haven’t got enough road or the house that blows up is in the wrong place,” says Bolter.

To achieve this precision Paino built two-metre models featuring houses and cars, allowing action beats to be blocked. “We’d feed information back to Neil and Craig and go through the stunts, discussing how fast the truck needs to go to smash through cars and how fast the kids are able to safely run safely,” says Bolter. “VFX had their say and then building the cul-de-sac began. What we planned is exactly what we shot.”

Episode five marks the first time true moonlight is seen in the series, the characters are in the middle of nowhere and there are no other sources of light. “So, the cul-de-sac sequence and walk and talk leading up to it was an extremely big moonlight sequence,” says Bolter, whose favourite area to work in as a lighting cinematographer is moonlight and “was excited to take on a brief which was as demanding as they come in terms of the size of the set and achieving a naturalistic, large-scale moonlight with multiple cameras whilst walking and talking.”

When creating moments of tension that are peppered throughout his episodes, the approach was always driven by perspective. In episode four, Ellie climbs through a wall and hides on the other side, while violent scenes unfold on the other side. “We chose to be with Ellie on that side of the wall and see and hear her react as it was a more interesting character led way to build tension than shooting it like a traditional action series,” he says.

“It was always to do with what we show, what we don’t, what can sound help us with, and when is it more interesting to stay on a face rather than see something. Particularly when it comes to human violence, you must ask yourself why you’re showing it. If everything is character based, usually a reaction to violence tells you more story than just seeing gratuitous violence.”

The same technique was used when two characters die at the end of episode five. The violence is not seen by the audience, but they still feel it through the reactions of others. Bolter also credits this “less is more” approach to Mazin’s writing and the skill of series editors Tim Good, Emily Mendez, Cindy Mollo, and Mark Hartzell.

In line with the grounded reality approach, capturing scenes inside the real car on the open road offered advantages with regards to realism. But some aspects could not be controlled such as the weather or shutting a highway for five miles to create a post-apocalyptic world. For episode four’s road trip to take advantage of practical shooting, while avoiding some obstacles encountered when shooting on location, a mixture of real on location sequences in the car and some on blue screen sound stage was used.

Having shot much of Night Teeth in a car on a sound stage, Bolter was experienced in concealing the use of blue screen. “The inherent flaws on the road are what make it real – the fact the light isn’t quite perfect, it’s bumpier than you expect it to be, the windows are dirtier than you expect them to be,” he says. “So, if you get onto the stage and lock it off, have wonderful lighting, and everything’s perfect, it feels fake. You need to introduce those flaws back into your lighting setup.”

Bolter uses a large soft source above for the sky and picks where the sun is. On this occasion a dolly track was used, and the sun moved subtly left to right to feel like the car making small turns in the road. The car was bumped significantly on a hydraulic rig and the windows were slightly open so wind machines could create movement in the characters’ hair. “You make sure the windows are really dirty, so a perfect blue screen can’t be seen through them,” he adds. “You make everything worse to make it feel more real. I love using LED screens for this type of work too, and had we had more car work, we perhaps would have gone down the virtual production road.”

Lighting lessons

Paul Slatter – a British gaffer who has called Vancouver home for the past 20 years – was instrumental in crafting a believable Last of Us world. As Bolter mainly likes working with LED and having full control over lighting, he moved away from the more tungsten approach from episode one, instead opting for LED with a little HMI for direct sunlight.

“Paul saw how hands on I am with lighting, colour, and lamps and gave me a new monitor with the current lighting setup as a live display. When I was with Dylan at our DIT cart talking about various lamps, I had the map in front of me with the brightness, colour temperature, and so on of each lamp on screen.” This allowed tweaks to be made quickly and efficiently and proved so helpful Bolter requested the same set-up when he shot Marvel series Secret Invasion.

The cul-de-sac in episode five combined multiple forms of illumination – a moonlight walk and talk and a burning house – but when shooting nights on a backlot the weather in Calgary was likely to be rainy and windy. “I knew if I had big balloons and textiles, they would need to come up and down constantly. But I’d seen DPs working on a small scale using ladder systems of LED tubes, so we looked at scaling the concept up.”

Rather than working with textiles, Bolter and Slatter created softness using large scaffolding rigs filled with 100 LED tubes. “We ended up with 400 six-foot bi-colour LED, waterproof tubes on four cranes covering the whole cul-de-sac pavement, producing a soft fill light which I could subtly bump up 1% or 2% mostly for moonlight, but then when the fire started, I could change it to a fire colour,” says the cinematographer.

In line with Bolter’s concept for moonlight being mostly backlit with a little side light, the grounds were circled with 26 lifts with two S360s on each. “It was too big a space to have just one moon – the shadows would have been crazy – so I used a sports stadium concept, where I could turn off the whole near-side of the lights to have 180 degrees of backlight relative to wherever the camera was.”

To avoid cross shadows on the floor, for each of the S360 cranes Bolter used 30-degree egg crates to funnel soft light in areas, so the actors walked out of one section of moonlight and into the next. This avoided shadows crossing from multiple sources and created the effect of one single source like the moon being very far away rather than one big lamp close to the set.

Dino lights comprising nine individual tungsten bulbs were used on the ground behind the flaming house to add more punch to the fire. “Anytime we turned away from the fire, the real fire worked as a backlight around characters, but it didn’t throw light a great distance. So anytime we looked away, the Dinos came out either side of the firehouse to punch some fire light. By dimming the tungsten up and down the colour balance goes up and down like fire as well. We put it through a half CTO frame to warm it up again from tungsten to closer to fire.”

When the fire started, Bolter wanted it to take over and become the major key lighting with the moonlight still in the background. “We wanted it to feel like hell had opened, here come the monsters, let’s embrace the chaos. In line with my desire to have fire everywhere, the SFX team came up with the idea of lots of bits of house and wood landing on the pavement after the explosion and creating embers which also motivates smoke being everywhere and in picture fire that’s not directly at the house.”

From chaos to calm

To perfect the battle sequence a sizeable storyboarding exercise was required and models were used to block the action in big strokes. Bolter, Webb, and storyboard artist Colin Lorimer created a form of comic book to preconceive the scene shot by shot, talking through the bigger stunt or VFX-heavy sequences with VFX supervisor Alex Wang, so previs could be created to present to the show runners and cast and ensure everyone was on the same page.

“The collaboration with VFX was excellent as they tried to enable us as filmmakers. This wasn’t a production where we were forced to make things easier or cheaper for VFX resulting in compromises, we could talk through various approaches and everyone make a decision together on the best approach.”

Bolter and Webb knew after the chaos of the battle, more intimate moments would follow between Ellie and Henry’s brother Sam in the motel and that the contrast would allow the audience and characters to take a much-needed breath. The operating style and approach to the shots also reflected this. “It was like, we’re safe just for a minute – let’s enjoy this momentary pause before the next thing happens. I’m proud of the lighting for that calmer scene as early on I knew I wanted to have just a single lamp lighting the two kids, and Henry and Joel, the two father figures, also lit by that same light. Key grip Spike Taschereu was also an essential part of the lighting as in the American system they handle all the flags, and cranes,” says Bolter.

“Getting the lamp in a position that worked for the two children and the adults in the other room as it shone through the open door was important. I was excited to go from the biggest lighting setup I’ve ever done on the cul-de-sac over three weeks of night shoots using tonnes of lighting to just a single lamp. It was an enjoyable contrast and perfectly demonstrates the scope and ambition of this unique series.”

–

All images courtesy of HBO/Warner Media with selects from Eben Bolter BSC.