A CUT ABOVE

With The Outfit’s action playing out in the shop of a master tailor, it is fitting that a master of the screen craft, Dick Pope BSC, captured the intrigue and stillness of Graham Moore’s stylish and considered thriller.

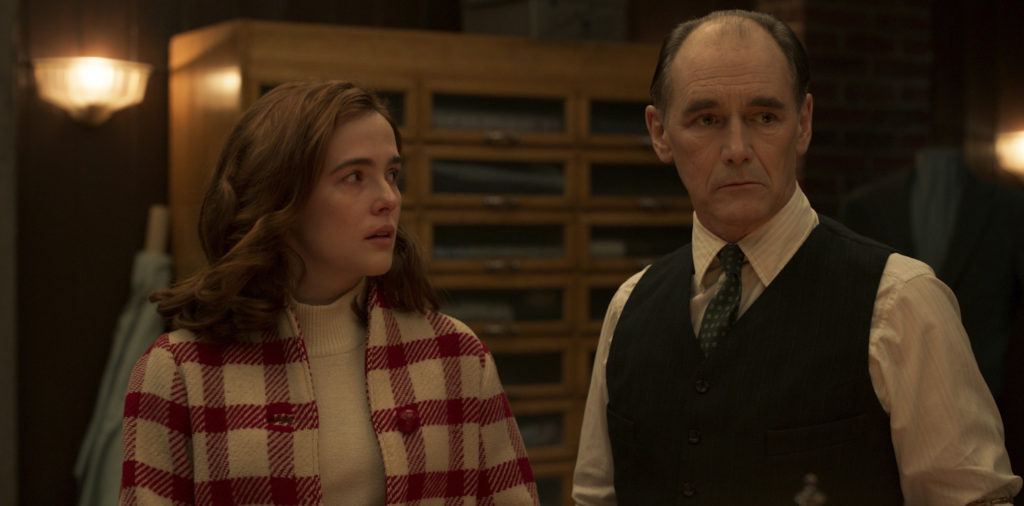

An intimate tale of mystery, betrayal, and suspense plays out in a 1950s tailor’s shop doubling up as the headquarters for mob activity in novelist and screenwriter Graham Moore’s directorial debut, The Outfit. Leonard Burling (Mark Rylance), a seemingly mild-mannered English tailor who has relocated from Savile Row to Chicago and become entangled with a gangster family, is the centrepiece of the thriller. Over the course of one night, the stillness and calm of Leonard and his shop are disturbed by bloody violence. Secrets, lies, and characters’ true identities are revealed as the gangsters Leonard is keen to distance himself from attempt to expose a rat.

Dick Pope BSC was shooting Supernova – Harry Macqueen’s directorial debut – in the Lake District when he was first approached by Moore (Oscar winner The Imitation Game) to shoot The Outfit. “Right off the page, this was a compelling and beautifully written script, and I found the visual challenge of it being entirely set in the one single location a very exciting proposition. I was somewhat concerned before my initial conversation with Graham about how he intended to shoot it and in what style, but he allayed any fears I might have had when I quickly realised his visual ideas exactly mirrored my own and he wasn’t naïve to the fact that we would have to be so very organised and structured to shoot this weighty script in only the 25 days planned.”

Over a year later, during the pandemic, prep started.

Even before prep began, and while Moore was still in Los Angeles, the pair talked every day on Zoom “in great detail” about the film. Moore emphasised that he wanted it to be a “considered piece with very quiet photography” in the same way that protagonist Leonard was meticulous and calm. The methodical manner in which the tailor – or cutter, as Leonard points out – made his suits needed to be visually mirrored by the cinematography. “Graham told me he wanted the film to look like one of Leonard’s suits, that there should be a classicism about it, beautiful and elegant with everything precise, but not static. He wanted to move the camera constantly, never handheld, but always tracking on a dolly, with every motion of the camera precisely coordinated with the motion of the actors, moving with the actors’ bodies, just like a suit would.”

Being staged in three rooms within a single location; Leonard’s tailor shop in 1956 Chicago, The Outfit possesses similarities to a theatre production. But Pope believes this is one of the film’s strengths and was determined to make it as cinematic as possible, diminishing this theatrical element.

“Yes, we are confined within the environment of this small tailor’s shop but what’s going on inside is sufficiently compelling that you don’t wonder what’s happening on the other side of that front door,” he says. “Very strong intimate cinema can result from bouncing off walls and doorways. We’re trapped in here, but it’s not an unpleasant place to be — a cosy kind of claustrophobia where gestures and glances are amplified, and being close-up and personal takes on great importance, focusing our attention and making us wonder what’s coming next. Leonard is very meticulous, considered, and quiet, but always observing, hyper-aware of what is happening around him,” says Pope. “So much of the film is centred around his looks that we had to be bold when it came to shooting close-ups because the visual language of the eyes and face, and not only his, was so important to capture.”

This influenced the decision not to use handheld or Steadicam which would have interfered with the calmness of Leonard’s work and environment. The film was to be closely observational and possess a smoothness that would not conflict with the quiet and stillness the narrative and performances revolve around.

“Even though this was to be Graham’s directorial debut, he was incredibly confident and assured about what he wanted to achieve,” says Pope. “He had worked on the script with Jonathan McClain for so long, really considering every aspect of the film, so came very well prepared indeed which resulted in a great collaborative experience for everybody behind and in front of camera.”

As capturing the material with which Leonard worked, in all its glorious detail, was key, Moore’s look book featured many references relating to the photographing of fabric including many images of Savile Row in the ‘40s and ‘50s. This motivated the early decision to shoot on large format ARRI Alexa LF to make the most of the fabric being captured.

“I wanted Graham to compare the large format with the normal Alexa and he just loved the way the material looked when shot with the LF. The large sensor also offered rich image texture, beautifully intense blacks, and natural skin tones.

“We then pondered as to whether to shoot widescreen 2.39:1, but that just seemed too wide for the small space in which we would be working or 1.85:1 which offered more headroom than we wanted and didn’t lend itself so well when dealing with group shots of multiple characters in the same frame.”

Pope and Moore settled on shooting at 2:1 – a format the cinematographer had not used before but had admired the results achieved by Barry Jenkins and James Laxton ASC in If Beale Street Could Talk (2018). “I loved shooting on this format,” says Pope. “Sharing the aspect ratio of many traditional canvases it was ‘painterly’ whilst also helping to frame the characters in the intimate interior without feeling boxy”.

Zeiss Supreme Primes delivered exactly the lens character Pope desired for the film and prior to testing he had largely already decided he wanted to work with them having discussed the Supremes at length with John Buckley at Movietech. “John knows what I like and thought they would be the ideal large-format lens choice for me. The tests proved he was right. They looked gorgeous. I didn’t carry a Zoom.”

The Outfit was captured on two cameras, with Pope operating one and long-term collaborator Lucy Bristow expertly operating the B camera. “For the scene where Richie is being stitched up on Leonard’s worktable after he’s been shot, we considered using rigs from the ceiling that would take the weight of the camera and allow us to swing around, but in the end, I decided against it. Instead, I put a dolly on either side of the worktable, and we slid in and out which was much more low-key, and very precise compared to a wire rig,” he says.

Maximum mood, minimum disruption

Taking place at Wembley Park Studios in London at the beginning of 2021, full COVID protocols were in place throughout the single-location shoot. “When Graham arrived, the set was just being put up and we had our office upstairs, so it was easy to walk down to the stage and discuss any given scene with production designer Gemma Jackson and her team while the set was being created,” says Pope. “We were all together in the same space which was wonderful.”

The palette he chose for the period film was heavily influenced by Jackson’s set; a dowdy shop in the backstreets of 1956 Chicago, but inside all polished wood and dark leather, with many hints of Leonard’s Savile Row roots. The excellent costumes created by Sophie O’Neill and Zac Posen also matched the ‘50s mood perfectly. “Everything that came together within the walls of that set lent itself to that period feel, so palette-wise I was very happy to go with what was there,” says Pope.

“In our prep period I spent a lot of time talking with Graham about how we would convey the passage of time with the changing of the light, and how it would play inside and outside the shop as the story unfolds. “We start at dawn and end just after sunrise 48 hours later, so it was most important to keep the lighting exactly right to ensure the mood was always correct for every scene filmed. I wanted the light to move from daytime to dusk to night, and for shadows to shroud the space, turning it from a relaxed sanctuary to an altogether more threatening environment. Outside, we see the city’s usual cold wind blowing through the streets and sometimes snow falls, giving the small shop a magical aura. It looks as if it has fallen out of time – and to a certain extent, it has.

To guarantee the shoot could be completed within 25 days, Pope had to make sure the lighting was not complicated and could quickly be adjusted to suit these different moods of day and night. During prep, he strove to keep the integrity of the set Jackson had envisioned, while engaging with her in many conversations about the position and size of the skylights in the main showroom, how the light from the windows was to hit elements in the rooms, and what the view, if any, would be outside of those windows. “For instance, Gemma had great ideas about sliding doors with amber glass which fitted in well with the mystery of the narrative,” he says. “She did an incredible job creating such a wonderful and authentic set.”

Practical lighting was also considered in depth, including the Tiffany lamp sitting in the middle of the showroom around which so much of the story plays. “We needed to think about what practical lamp would work for us aesthetically as well as being a source of beautiful light and went slightly to hell and back in trying to make the one fixture work for everything whilst placed in the middle of the room,” says Pope. “That one practical lamp became a real key player.”

The cinematographer and his long-time collaborator gaffer Andy Long – who Pope ensured was on board for all of the short four-week prep period – installed a sizeable rig in the four open pockets of Leonard’s showroom ceiling.

“Andy took my concept for lighting directional but softly from above but that didn’t look like it was from above, and made it work,” says Pope. “Especially at night, the light had to appear to be sourced from the practical fixtures around the room. Andy designed a brilliant rig above that made this a reality, creating a 360º rig of approximately 18 ARRI SkyPanel S60s installed above the set.

“Beneath the rig lay four custom-made approximately 9’ square ½ silk frames to soften the light. Ceiling pieces and cutters could be slid in when necessary. These SkyPanels were used selectively, never all playing together, sometimes nearly all off and dimmed right down creating just small pools of light. Every unit, including all practicals, went back to console operator Adam Bullock’s desk. Carrying his iPad on to the set, allowed me right there to control the colour, intensity, and mood, quickly able to create morning, noon, or night. Amongst other units, Astera Titan tubes, china balls and S30s were brought onto the floor when necessary for modelling”.

The same idea was employed in Leonard’s workroom and also for lighting the street viewed outside the main window of the shop.

“Apart from Andy Long, key members of my crew included Lucy Bristow, key grip Colin Strachan and 1st AC Graham Martyr, who go way back with me as well as makeup artist Christine Blundell who I’ve worked with since the early ‘90s. What she achieved in this film, especially with the prosthetics for the wounds, was just genius. They’re all great people and bring so much to any film. I love them – they’re like family”

Achieving maximum mood with minimum disruption to the actors’ performances during the dialogue-heavy production was essential to the shoot’s success. One of many elements that made this possible was the light in Leonard’s workroom – an old-fashioned snooker table light which Pope installed with a variety of different bulbs throughout the shoot according to the mood required. It enabled the light to hit Leonard and the work he was preparing on the table, while the rest of the room fell away into darkness.

“The actors needed the maximum amount of time, so the focus was placed on orchestrating and choreographing scenes – sometimes featuring most of the cast – and how we’d cover the action, rather than me being concerned on the day about changing the lighting, which of course we didn’t have to do with our composite rig. We just wouldn’t have made the schedule without it,” says Pope.

“We used the ACES colour management system. During prep at Dirty Looks in London a base LUT was built in ACES by colourist Adam Inglis, and this was used for the dailies. This LUT helped retain detail in the fabric and texture of the period clothing but gave a slightly antique feel to the overall image. “Due to warm tones in the wood and brickwork, we steered towards green and yellow whilst warming highlights to help soften skin tone. Using this base LUT as a starting point, DIT Kevin Bell graded directly on set. The dailies looked great and were produced by Jordan Altria at Harbour in London, but Kevin did a terrific hands-on job of providing the CDLs and the film’s on-set grading for Jordan to work with. This meant there were no drastic changes for Harbour to deal with, just some subtle touches to help match between the A and B camera when needed.

“For the DI at Dirty Looks in London, we used the same LUT as a start point but graded the film in ACES. When Adam first ran it through, the camera original was very consistent from the outset and happily for me appeared to have already been subject to a first pass.”

Pope’s “obsession” with the transition from day to night continued right through to the grade. Following the edit, Moore, and editor William Goldenberg (Argo, Zero Dark Thirty, The Imitation Game) informed Pope that because of the way they had cut several scenes together, one had too much daylight for the intended time of day. “When they asked if anything could be done to bring it back to more of a dawn feel, I told them there was little that can’t be achieved in the DI suite,” says Pope. “Very quickly in the DI, Adam resolved the problem and removed the slightly day-lit look to bring it back to a more nocturnal mood.”

Closely observed choreography

In his role as cinematographer, Pope revels in “the dynamics of what is in front of the camera” and was deeply immersed in the actors’ choreography throughout the creation of The Outfit, closely observing the scenes as they were rehearsed. “And then when we were shooting, I would be alongside Graham, on set well before the actors arrived, further suggesting ways in which we could stage scenes to create the most tension and drama, but always ready to adapt.”

The environment in which the cast and crew were working was very small, but the team contrived ways to differentiate between the rooms, using the sliding doors and framing in inventive ways.

“It was a lot of fun to create moods and tension within a small set,” says Pope. “It was a challenge I relished as I have no problem filming in confined spaces, having done it frequently in the past.”

The action always has a sense of clarity, with blocking and lighting that keeps the geography of each sequence legible, enough that any movement from one room to the next is accompanied by anticipation.

The climactic and increasingly violent final scene adopts more movement and was shot on one dolly with two cameras – a technique Pope uses often.

“One camera has a wider lens and the other tighter, so you’re not exactly reproducing the same angle. They’re separated slightly, so it’s a different perspective,” he elaborates. “They cut together so well because it’s the same action. You’re just covering it once with two cameras. You can then run another take and get those two cameras covering a different piece of the action, with cutting points always correct because it’s just one take from two angles. Mark Rylance had never seen two cameras used in that way and was fascinated by the technique.”

While Rylance was captivated by the production process, the crew were equally enthralled by his performance and methodology on set. “He had a microscopic attention to detail,” says Pope. “It was fantastic to be there and watch him work. He was a natural at orchestrating scenes and shifted his character’s demeanour, moderated his behaviour, staying in calm control of an increasingly volatile situation. It was a thrill to watch such a master craftsman at work. He’s just such a genius. The working relationship I shared with Mark and Graham Moore was one of the many rewards of the film.”