LIFE THROUGH A LENS

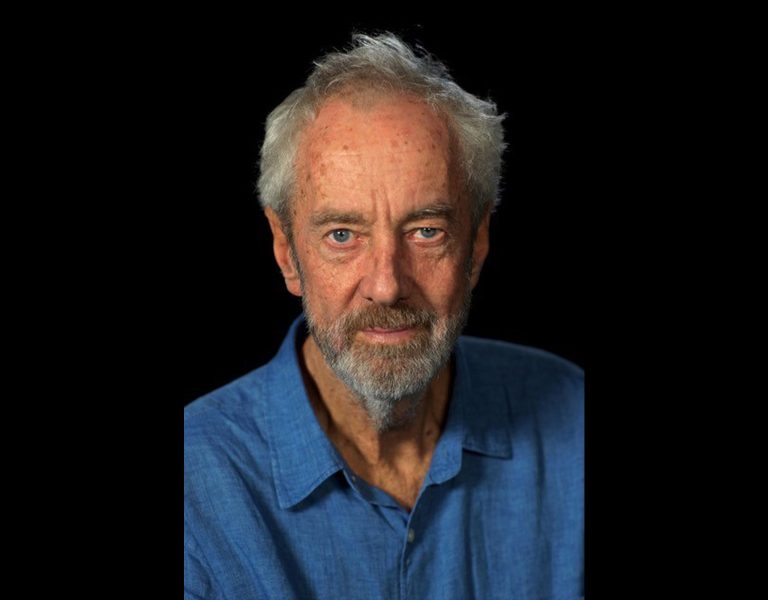

One of the most understated and respected cinematographers of his generation passed in October, leaving behind a body of work that can’t be matriculated by awards or nominations.

Richard Pope, known as Dick, was born in Bromley, Kent in 1947. An early appreciation for stills photography came from his father who gave him a Box Brownie and let him use his Zeiss twin lens reflex camera.

“The camera was particularly suited to portraiture and Dick began to recruit potential subjects from his neighbourhood, turning his lounge in Kent into a makeshift studio,” records Phil Méheux BSC in the book Preserving the Vision. “He had also become a regular at his local cinema, where he developed a strong passion for film and decided to combine his love of photography and cinema into a career as a cinematographer.”

Aged 16, he began a three-year apprenticeship at the Pathé Film Laboratory in Wardour Street, Soho. In 1968, having tried unsuccessfully to join the BBC, he went freelance and became a clapper loader on low-budget British sex comedies like Loving Feeling which, according to Méheux, felt far away from his ambitions.

By 1974, he was filming documentaries, travelling to remote and hostile areas including war zones for films about endangered indigenous tribes for Granada series Disappearing World (1974), political journalism for World in Action (1976-8), and arts programmes for The South Bank Show.

During the 1970s and into the early 1980s he operated on hundreds of rock concerts, many for BBC’s The Old Grey Whistle Test and shot music videos for artists including Tina Turner, The Police, and Alison Moyet. He shot The Specials’ ‘Ghost Town’, Queen’s ‘I Want to Break Free’ and Kylie Minogue’s ‘Wouldn’t Change a Thing’. Other promos included for Madness (‘It Must Be Love’), Fine Young Cannibals (‘Suspicious Minds’), and Rick Astley (‘Hold Me In Your Arms’).

He moved into television drama in the early ‘80s, earning a BAFTA nomination for his work on 1987 comedy mini-series Porterhouse Blue before being invited to shoot his first narrative feature as DP. This was Welsh language comedy Coming Up Roses (1986) for director Stephen Bayly which screened in Un Certain Regard at Cannes and on which a mutual colleague of Mike Leigh suggested they ought to meet.

“I’d worked with Roger Pratt BSC on High Hopes and expected to go on working with Roger but he was busy with Terry Gilliam shooting The Fisher King,” Leigh explains. “Roger was very, very apologetic but I needed to find someone else. Working with Dick just seemed like a good idea. He was a great guy, we talked the same language and it turned out to be a great relationship.”

The comedy Life is Sweet (1990) was the start of a hugely successful career collaboration between Leigh and Pope which spanned 12 features plus shorts and commercials.

“Once we’d worked together once it was dead obvious we’d work together again,” Leigh says. “First of all, he’s a brilliant cinematographer and that was clear from the word ‘go’. We also shared a sense of humour, we shared a sense of cynicism and we shared taste.”

Their next feature collaboration, Naked (1993) is arguably their most celebrated. The coruscating satire of class, power, and sexual relationships won Leigh and actor David Thewlis awards at Cannes but it’s Pope who conjures the film’s monochromatic nocturnal bleakness.

“I go into a long period with the actors and there’s always an agreed point in the proceedings when I start to share with Dick and the designers what I think is emerging,” Leigh says. “When I did that on Naked I was able to say to Dick, ‘I think the film is kind of nocturnal, maybe monochromatic, although we knew we were shooting in colour. It’s about this guy on a solo journey and Dick was immediately on the case. The bleach bypass tests he shot were right on the button.

“It continued from there. Every time we made a film he absolutely tuned in on cinematically, photographically, visually, aesthetically, dramatically with exactly the right thing.”

This includes Pope’s use of bold primary colours on the optimistic Happy-Go-Lucky (2008) and his inspired use of Super 16 film to create the postwar world of Vera Drake (2004). Leigh highlights the combination of 16mm shot handheld with 35mm shot formally to differentiate between the past and present in Career Girls (1997) and his “beautiful rendering” of the four seasons in Another Year (2010). Other highlights include the sumptuous Victorian theatre imagery of Topsy-Turvy (1999), Pope’s sensitive references in Mr. Turner (2014) to the artist’s paintings, and his bold rendering of the turbulent world of Peterloo (2018).

What is notable about the critical acclaim accorded to Pope is that he did his best work without announcing his presence.

“I don’t think Pope had a signature [look],” observed Matt Zoller Seitz, an editor at RogerEbert.com. “Pope seemed like the cinematography version of a character actor, giving the performance that particular film needed.”

If there’s any aesthetic through-line in the work it relates to Pope’s “evidently unassuming intelligence about how best to serve material,” Seitz said. “He seemed to have an instinct for doing as much as he could to help a movie, a scene, or a moment without seeming as if he was trying to inappropriately spice things up or wow the audience or dazzle in some superficial or obvious way.”

In an interview for the 2021 remaster of Naked, Pope himself noted that Leigh’s films are full of “invisible moves”.

“People always think that the camera is locked down and doesn’t move in his films, like in the work of Ozu, but of course it does move. In the silhouette shot when Johnny is having his big rant at Brian about Nostradamus and the end of the universe, the camera is moving closer all the time into a much tighter shot, but it’s almost invisible, and you don’t realise it’s happening. That was what I tried to do – make it as invisible as possible, make it feel like you’re just being drawn in by the words, but the camera is actually moving in all the time.”

Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC says Pope’s legacy is one of unpretentious photography. “Naked is the epitome of that. It would have been so hard to shoot that film in those circumstances with so little money but he did it beautifully.

“He was very much a people person. Some cinematographers have a bit of a reverential view of themselves. Dick wasn’t like that. He was more ‘get in there and just do it.’ For Dick, it was all about the story, the characters and about working with people. He loved working with crews and just loved the experience of the job. He was willing to muck in and not have special treatment.”

Leigh has a similar take, “He wouldn’t have been able to function as an artist – which is what he was – if he didn’t have a great sense of compassion. He absolutely got what my stories are about and he was brilliant with actors and knew how to serve their needs. That’s very important, obviously, because my films are very performance based.”

Pope’s other work includes for Richard Linklater (Bernie, Me and Orson Welles), Christopher McQuarrie’s directorial debut (Way of the Gun), Barry Levinson’s Man of the Year, Douglas McGrath (Nicolas Nickleby), Brian Helgeland (Legend); Beeban Kidron (Swept from the Sea), Chiwetel Ejiofor (The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind), Harry Macqueen (Supernova), and Graham Moore (The Outfit).

When Edward Norton wanted to convey the loneliness of life in 1950s New York for his noir feature Motherless Brooklyn he turned to Pope. They had met on the set of Neil Burger’s The Illusionist (which earned Pope an Oscar nomination in 2006).

“Dick’s talent for making the past seem visceral is what made me want to go to him,” Norton told IBC365. “I used Robert Frank and Vivian Maier photos to convey the path I wanted to go down and Dick brought the idea of Edward Hopper paintings.”

Pope said of the project, “It’s a dream for any cinematographer to be asked to recreate fifties New York with all the visual flourishes of a noir. I was brought up on noir film. My father idolised noir actors of that era and was a number one fan of Dick Powell (whose Philip Marlowe in 1944’s Farewell My Lovely is considered definitive). That’s why he called me Richard.”

Pope was a favourite of cinematographers, winning the coveted main prize at Camerimage in Poland no less than three times. Particularly memorable for him was a presentation of Naked at the festival’s first edition in 1993. In the audience were Sven Nykvist ASC FSF, Vittorio Storaro ASC AIC, and Vilmos Zsigmond ASC along with students from many film schools in Europe.

“After the screening it became apparent that the students had never seen anything quite like it before,” Pope recalled to BFI curator James Bell. “They mobbed me in the auditorium then kidnapped me and took me to a smoky backroom where they demanded all I knew about everything to do with the making of the film and Mike Leigh’s method. Then at the end of the festival at the awards ceremony, the students mounted the stage and in a piece of pure agitprop, hijacked the proceedings and gave their own award to me for Naked, which is a beautiful piece I still have and treasure – a stained glass panel evoking Rosebud, the sled from Citizen Kane.”

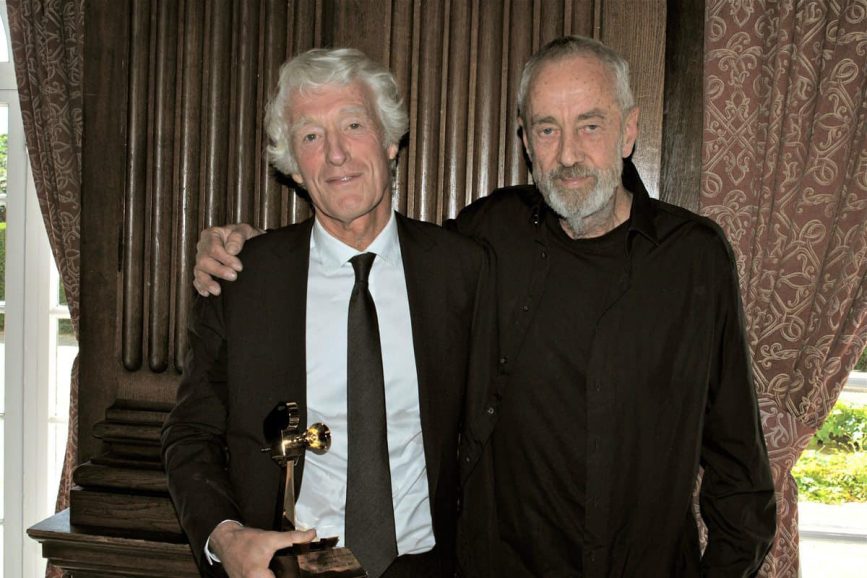

My friend, Dick

Starting their careers around the same time, it was inevitable their paths would overlap but Pope was to become much more than a colleague to Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC.

“He’s probably my best friend in the business,” says Deakins. “We started together and went through the same kind of evolution.”

They met in the late ‘70s at Solas Enterprises, a documentary filmmaking cooperative run by directors Jack Hazan and David Mingay. “I spent more time with Dick than I did with anybody else. He was working as an assistant at that time and making his way up to become a cameraman.

“We had a lot in common even though we had very different backgrounds. He’s very much a Londoner and I’m from the West country with very different characters but we got on really well. We’d sit in the office, have a cup of tea and swap war stories.”

When Pope landed work shooting concerts he would invite Deakins to operate a second camera. “I remember going up to Birmingham one weekend and filming The Clash with him,” Deakins recalls.

A few years later, shooting 1984 for Mike Radford, Deakins was able to return the favour, with Pope operating second unit. When Deakins went to Kenya to shoot Mountains of the Moon (1990) for Bob Rafelson, Pope shot second unit too.

“I knew he’d shot documentaries on the Maasai there with producer Chris Curling with whom Dick had already shot documentaries. Dick loved Kenya. He also loved just being off on his own shooting some shots for us. Once he’d finished he’d go off into the bush for days and we wouldn’t know where the hell he was but he always come back with one or two wonderful shots.

“That was the last time we worked together, but we’ve always kept in touch. Sometimes he’d come to stay with us in Devon or catch up over dinner in London. We even ended up both going to the Academy Awards as nominees (in 2015 for Mr. Turner and Unbroken respectively).

“We’re both very cynical about the ritual and pomposity of filmmaking which is perhaps why we got on so well. Dick had a wonderful way of undercutting all of that and not letting it get to him.”

Deakins and his wife James describe Pope’s sense of humour as “nuts” and “left field” adding, “He was charming and funny and he had a great deal of curiosity. He was so enthusiastic and loved film. Every time he had a movie coming out we looked forward to seeing how he tackled that particular challenge.”

Deakins adds, “I just really miss him as a friend. I don’t think it has sunk in yet.”

A perfectionist

“He was extremely creative in terms of how he thought about light,” says Lucy Bristow ACO Assoc. BSC, who loaded on Life is Sweet and operated on Hard Truths, bookends of a career on which they paired on numerous other projects. “He could turn something very bland into something very beautiful. Dick crafted everything and was always striving to improve the shot. He was like a dog with a bone and wouldn’t leave it alone. He had incredible perfectionism.”

When Bristow graduated from loading to operating, Pope encouraged her to go into the grade and pursue the film’s look into post. “He impressed on me the importance of understanding the whole process, including beyond the end of the shoot. He was also fantastic at making actors feel comfortable. He had a wicked sense of humour. That’s what crew and actors respond to on set.”

Bristow also recalls working with Pope in Ghana on a tricky nine-week shoot for HBO TV movie Deadly Voyage in 1996.

“So many things went wrong including the generator bursting into flames in the middle of the night, actors getting bitten by dogs, and the second AD getting sepsis from a fall and having to be airlifted out. The Ghanian crew felt the film was so jinxed, they even got a local healer in to bless the rest of production. Of all the films with Dick this was the most eventful as an experience.”