MAKING THE GRADE

Special Report / DI Grading

MAKING THE GRADE

Special Report / DI GRADING

BY: Michael Burns

During this magazine's lifetime, the role of the person overseeing colour has evolved, from a technical stage in post-production, to becoming an integral part of the whole workflow. Highly-creative, today's colourists also collaborate more closely with cinematographers and, increasingly, colourists are seen as part of the camera team.

The change began as technologies were developed to scan celluloid film digitally, apply colour correction, and output the results back-to-film. That process was given the term 'Digital Intermediate' (DI). Today, that stage may not be so common, and whilst retaining the name, it may no longer be the same essential process in a fully-digital workflow either, but it changed post forever.

"There is a skillset or process that did not exist before DI," says colourist Peter Doyle, now at Warner Bros. De Lane Lea, who, as long ago as 2001, used SACC (Stand-Alone Colour Corrector), developed by Colorfront, to grade Peter Jackson's The Lord Of The Rings: The Fellowship Of The Ring (DP Andre Lesnie). "The scale of this can be seen everywhere in the fact that all films, with a few exceptions, have adopted DI as a process. That's really a testament to the impact on the industry."

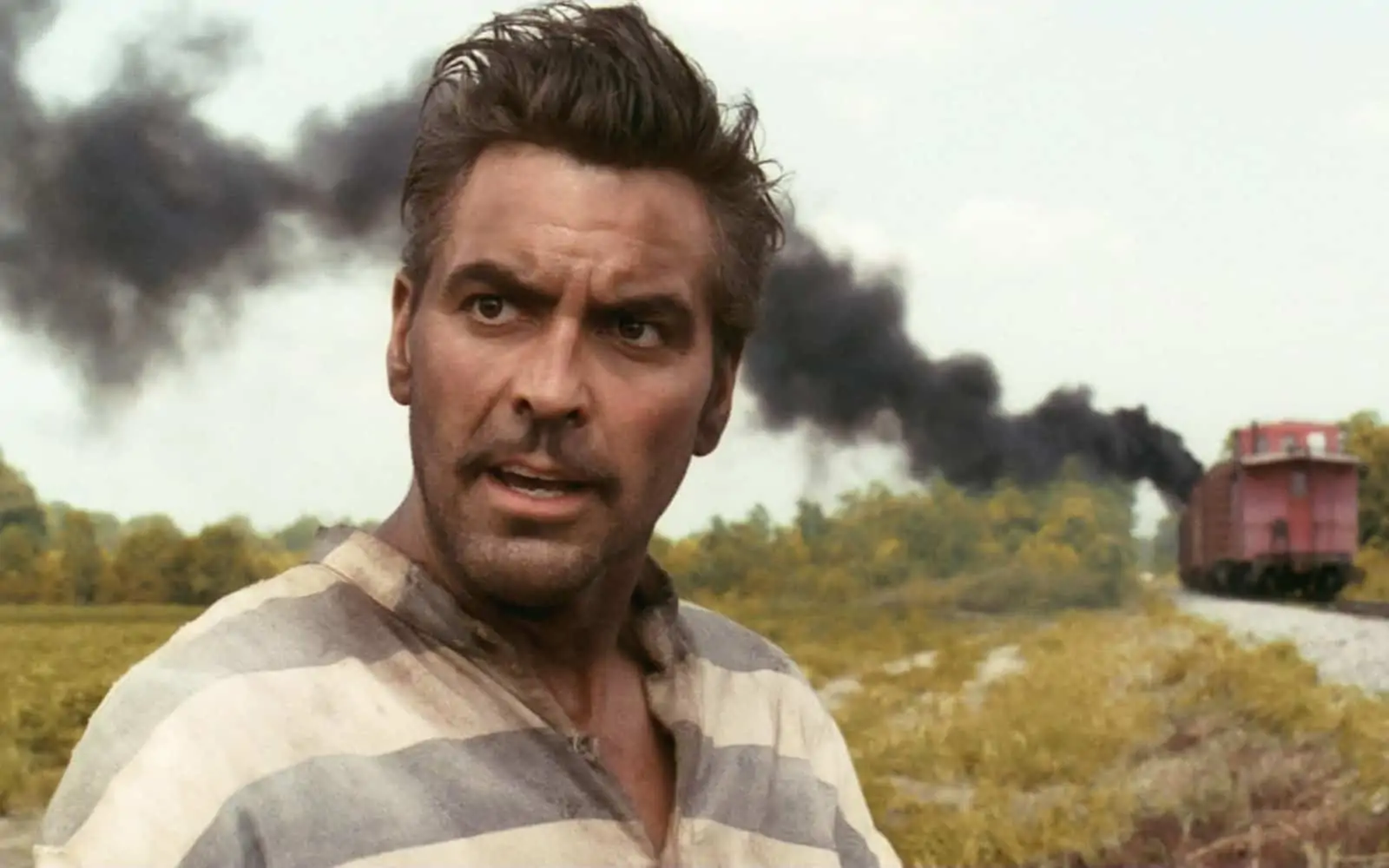

"I think Oh, Brother Where Art Thou (2000, DP Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC) was the first film that was a complete digital intermediate, whereby every single frame was graded digitally," says Toby Tomkins, MD and colourist at London grading boutique Cheat. "Roger Deakins recognised that trend early. He has mastered this new medium and he hasn't gone back to film. We're starting to see that across the board now."

"The first DI I did was Underworld (2003, DP Tony Pierce-Roberts BSC)," says Jet Omoshebi, senior colourist at Goldcrest. "That was cutting-edge technology, and it was much more hit-and-miss, than it is now. It was still very unusual to shoot a film on film and finish it digitally rather than in the lab."

Primary colours

However, it was the creative possibilities that digital engendered which appealed.

"Since the beginning of celluloid film, cinematographers would shoot very specifically what they intended," says Stefan Sonnenfeld, colourist, executive producer and owner at Company 3. "The lab process was sort of more of an enhancement, if you will, rather than what the DI process is today. Obviously it can still be [considered] enhancement, but also you can change things quite significantly. That's the whole point of the process, the flexibility of creativity and artistry.

"Using the DI process to manipulate the colour, to give different parts of the movie different feelings and emotions is a latent tool of colouring," continues Sonnenfeld. "It has this enigmatic or sometimes hidden way of pushing through feelings and emotions, whether that be subtle or dramatic. That's the beauty of it."

One of Sonnenfeld's favourite DIs was Tony Scott's Man On Fire (2004), with Paul Cameron ASC as DP.

"Tony was a trailblazer in the sense that he just always wanted to be able to have the utmost creative flexibility," says Sonnenfeld. "In Man On Fire, he wanted to evoke different emotions for Denzel Washington's different states of mind using colour via this new DI process. We were able to manipulate the image specifically for Tony's emotional intentions throughout the movie. It was one of the first times in my opinion that was done with the process, and very effectively.

"Initially, some people were hugely behind it, people like Tony and Michael Mann and Ridley Scott, some of the legends were very supportive of and complimentary of it, because they had such flexibility," he continues. "There are some tremendous cinematographers like Dan Mindel BSC ASC, Henry Braham ASC, John Schwartzman ASC, who really loved the process too. But a lot of people were hesitant, there were some very big naysayers. And then it turned."

Secondary colour

Overall, Peter Doyle feels colourists have more creative input now than in 2002, "but the degree of involvement is very dependent on the dynamics of each production."

Sometimes the power of digital grading can leave the idea of colour correction in the dust. Sonnenfeld's work on Zack Snyder's 300 (2006, DP Larry Fong ASC), for instance.

"I think 300 is a perfect example of the extreme," says Sonnenfeld. "We'd been doing that work in music videos all the time. All of the whole look of 300 was basically created in the transfer and in the DI. Zack is an innovative guy who always pushes the boundaries of everything that he does, and DP Larry Fong as well.

"It just illustrated, if it's done well, how very effective and super-creative digital grading can be," he continues. "The whole point of our business is to push the creative envelope, to give our clients and DPs the highest level of artistry we can with the most flexibility, and to do it in a way that is compelling, technically correct, at the highest levels of resolution and security."

The concept has now come full circle with fully-digital productions being engineered through the colour process to look like they've been shot on film.

"We've honed the process," says Sonnenfeld. "At Company 3, we can replicate things mathematically, like the Technicolor look from years ago that was only able to be achieved through lab work."

Going with the flow

With the proliferation of formats for acquisition and the even greater proliferation of deliverables, an agreed workflow between all points of a production has become more essential than ever.

"The concept of workflow has always been very important to me," says Doyle. "The specifics change with each production. The benefits are fewer redo's, variables and less repeatability."

Doyle sees moves like the implementation of ACES, the Academy's digital image file interchange and colour management system, as a positive trend than gives more room for experimentation.

"For example, we know how the camera reads the light," he explains. "We know how the displays will show the light, so the DP and colourist can take control and create their own aesthetics, with the knowledge of how it will translate to theatre or home."

Such collaboration can take place during pre-production, developing looks based on camera tests.

"Back in the film days, they'd choose a negative stock, and the print stock, and that pretty much defined look of the film," says Tomkins. "As colourists we're now involved early-on, generating looks and Look-Up Tables (LUTs) so that directors and DPs can view the final intent of the image on-set. It's similar to seeing the dailies on your target print stock with the printer light values and adjusting that as you shoot. We're now doing that via LUTs."

"However, you're generally not involved all the way through shooting," says Omoshebi. "You might dip and out, look at odd shots or problems. You would probably hand over to the digital imaging technician (DIT) on-set, who then produces a colour decision list (CDL) of the changes that they make, so that when you get the final project, you can track everything that's been done on on-set grading-wise."

"There are definitely factions to this among cinematographers, but I think DPs are starting to adapt to the fact that what they are shooting is sort of an intermediate capture of the scene," Tomkins adds. "The general trend is slowly edging its way towards optimising the capture to the end result and not seeing the capture as the final result. That's a seismic shift from establishing the world of colour onto the film negative. The future of grading is about making the tools intuitive, very natural and scene-referred, as opposed to subjectively taste-referred."

Leading lights

Grading hasn't had a huge churn in applications and hardware. Blackmagic DaVinci Resolve has become one of the stalwarts, along with FilmLight BaseLight. Other systems in-play include, Autodesk Lustre (which evolved from Colorfront's original Stand Alone Colour Corrector), Assimilate Scratch, Digital Vision Nucoda and SGO Mistika. All offer a variety of cutting-edge tools to finely tune the grade, and all can handle High Dynamic Range, today's big trend in post.

"HDR with its larger colour space and dynamic range is slowly moving the industry towards the idea of one master version of the film, from which we generate the various delivery formats," says Doyle.

"With HDR it's not only the increased available range that you have in brightness," says Tomkins. "You can also have an increased range in individual colour channels. In HDR you can just use the range of one channel to keep the colour in those highlights without sacrificing the overall scene brightness. We used that a lot for The End of the F***ing World season two (DPs Benedict Spence and Ben Todd). If you look at the practicals in HDR on Netflix, they're much more pleasing than they would be in the SDR version."

"Celluloid film could always capture that resolution, but we could never resolve it," says Omoshebi. "We've gradually been able to resolve a greater proportion of the resolution of film. With HDR we can now capture the dynamic range also. You are able to give a much better rendition of what a cinematographer is shooting."

However, she points out that cinematographers have spent their lives relying on the mystique of the things that couldn't be resolved: "the lovely imperfections, the lovely lens flares and bends and distortions, the slight mist of film stock, that granular feeling as if you were looking at something that was living and breathing - that slightly gets stripped away," she says. "You have to be sure that you don't lose the things you love about making pictures. We are still telling stories. You have to be sure that you are able to maintain the magic."