Going Green

Special Report / Carbon Footprint

Going Green

Special Report / Carbon Footprint

BY: David Wood

Often lumped together as if they were the same industry, rarely have the differences between film and television been demonstrated as clearly as they have over their impact on climate.

Television production produces on average 20 tonnes of CO² per hour. Film produces thousands of tonnes per hour - many orders of magnitude higher.

Albert, the collaboration scheme between BAFTA, broadcasters and independent producers to address the industry's impact on climate, states: "An average hour's filming equates to the carbon footprint of a return flight from London to New York. The average tentpole film's fuel-use is the equivalent to a car driving 3.4 million miles."

To some extent comparisons between film and TV are unfair because the number of hours of TV produced is so much higher, but there's no doubt that television as an industry has less impact per hour on climate. It also has done much more as an industry to go green.

To date, and with the help of initiatives such as Albert, set up specifically to green-up the film and television industries, TV has made steady progress in controlling its environmental impact. For most producers now mitigating and measuring environmental impact is an essential part of the production process, not least because their commissioners (the BBC, ITV, C4, UKTV, Sky and Netflix) require it.

Sky recently stated that it had become the first UK broadcaster to make all of its original production carbon neutral as the company aims to be net zero by 2030.

Albert provides a carbon calculator for heads of production to measure impact. It has launched initiatives such Planet Placement, which encourages producers to incorporate positive environment messages in their content. And, at the end of the process, Albert provides different levels of certification relating to what extent a production has managed to reduce its impact.

Albert's website is brimming with examples of positive action and great ideas to reduce the environmental impact of TV production, but films which have gained Albert certification are fewer and further between. In fact, last year's feature 1917 (dir. Sam Mendes, DP Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC) was the first large-scale UK film to gain Albert certification - and, of course, it's the larger films that have the biggest impact.

To be fair the film industry has proved harder to reform that TV because of its intrinsic nature; no centralised commissioning processes to dictate green guidelines or episodic production patterns to decarbonise.

Industry consultant Ian Sherborn, a keen green advocate who has worked with a number of companies to instigate change, argues that the way film is organised makes reform more difficult.

"The transient nature of the production industry and the need to work globally present huge challenges," he admits. "The industry is heavily-reliant on services beyond its immediate control. To effect wide-ranging change, improvement is required throughout the entire supply chain."

So what is the film industry doing? To date the indie sector has led the way, with the British Film Institute (BFI) now requiring all productions that receive funding to complete an Albert report.

The BFI starkly concluded, in its March 2020 report on environmental sustainability in film, that a step change is needed in the film industry's efforts to help meet the UK's legally-binding carbon reduction commitments to be net zero by 2050.

One danger identified by the BFI was that US productions, which are hugely important to the continued success of the UK film industry, have their own alternative system of carbon calculation and sustainability certification through the Production Guild Of America (PGA) - known as Peach Pear Plum. This overlaps with Albert's approach, and it means there is no common standard and sustainability practices can vary widely. It also makes it less likely that US productions will easily accept Albert certification (which is more rigorous) without being forced to do so.

The BFI concluded that 'although attitudes to environmental sustainability are changing fast in the film industry, tighter regulation and obligations are likely in the near future'.

Melanie Dicks from environmental consultancy Greenshoot agrees that legislation is the real deal for film, forcing the industry to reduce impact and off-set carbon. "In the entertainment industry you need to lead by legislation to normalise it. It worked for Health & Safety."

Sustainability expert Dicks has worked with over 30 films including Fast & Furious, the St Trinian's franchise films and the BFI production slate, reducing carbon footprints and off-setting what cannot be reduced any more. Her company offers training courses for green runners who can advise different film departments on environmental best practice.

"Cutting CO² by 20% is really good. 15% is the average for most film productions if you do the basics - things such as switching over from high carbon light sources, like Tungsten, to LED lighting."

Sherborn adds: "The emergence of LED and low-energy lighting as a true alternative to traditional sources, has made a real impact."

In response to increasing demand for green technology for the film industry, studio and lighting companies have responded with plenty of innovations, from solar-powered studios to green generators.

"Manufacturers such as ARRI and Chroma-Q have introduced highly-capable products," reports Sherborn. "Large-scale investment, by companies such as Pinewood MBS Lighting, has made it viable to light even the largest productions, almost totally on low-energy sources. The choice is no longer whether or not to use LED, but which products to use."

Companies such as London-based, film lighting rental house, Greenkit, which offers over 90 different LED lighting options, are responding to the challenge. Founder Pat McEnallay realised, after working at Lee Lighting, Agfa and Panalux, that many gaffers, cinematographers and producers wanted to make more sustainable films but that they struggled to find green, eco-friendly lights that really performed on-set. After thoroughly researching the field, McEnallay discovered that, as well as being cheaper to run, energy efficient lights are also cool to operate, portable and can often run off batteries.

"To make it into our film lighting rental line-up, each fixture has to offer consistent, punchy lighting every time you switch it on," says McEnallay. "Most of our green lights have battery options or can run off domestic sockets. They tend to be lighter and more flexible than traditional equivalents. Advances in LED technology mean that now you can have a cool operating, colour-consistent fixture that's easy to work with in a small space. We're particularly excited about the new generation of RGB lights, which give a huge range of colours and effects without the need for plastic gels."

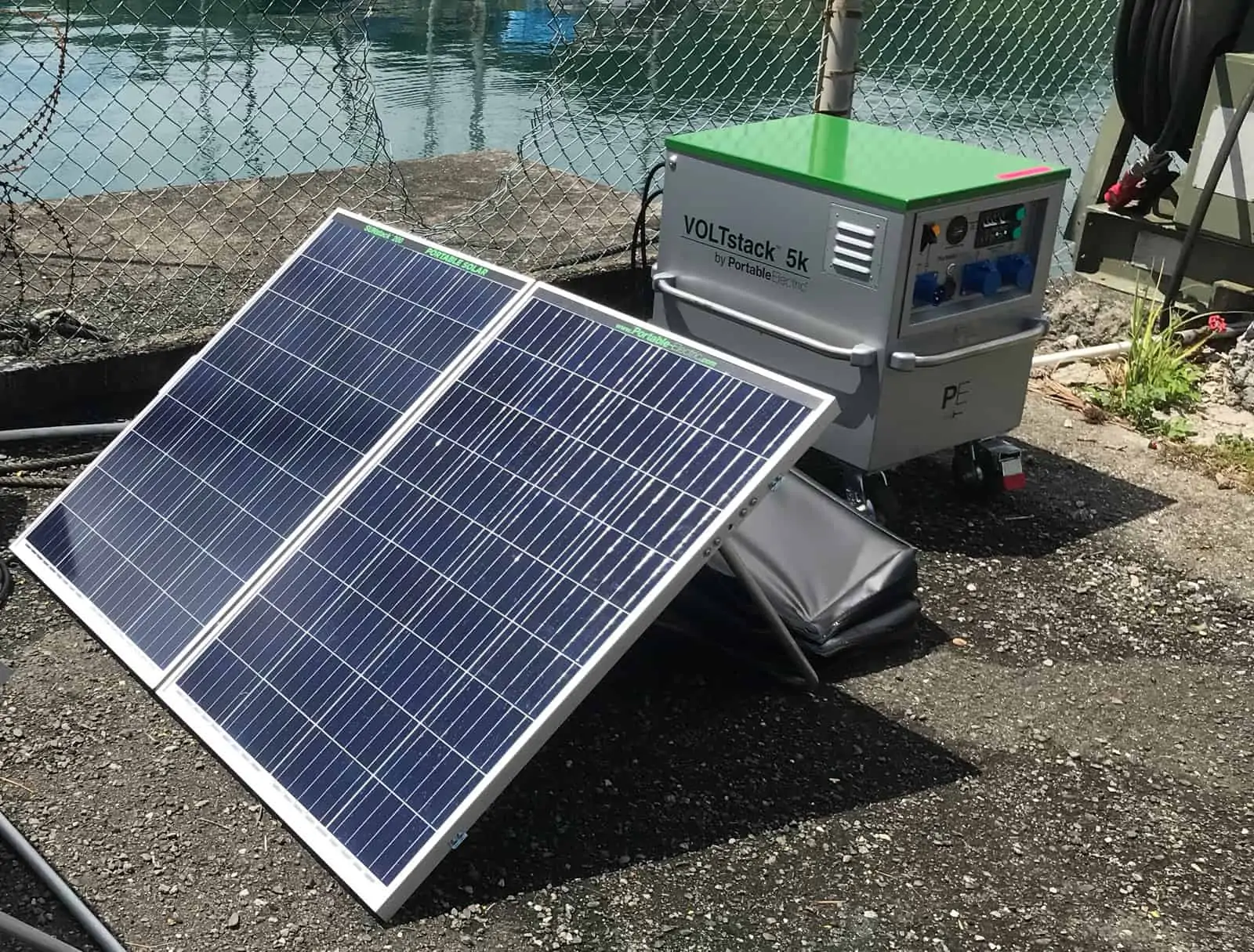

Recently there's been a lot of progress in the development of green power. The emissions-free, battery-powered generator units provided by Green Voltage make clean, silent power available to even the most extreme locations - a particularly effective solution when combined with the low power consumption of LED fixtures. Panalux Power's H40 hybrid generator is another example, giving the option of 30KW of power from its lithium-ion batteries.

Small incremental changes can have a significant effect too. Along these lines Albert has created a 'green rider', a draft contract for actors, casting directors and agents to stipulate that trailers run on renewable energy and on-set transport is electric.

Another initiative is the growth of a recycling industry around film production, with companies such as CAMA springing up to triage used films sets to store, sell-on or recycle materials rather than send them to landfill.

But, big changes are needed if film is to significantly reduce its carbon footprint.

Greenshoot's Dicks has been campaigning for green tax credits for years and declares that if the DCMS incorporated a 2% green tax credit the whole industry would be transformed overnight.

If there was one single change, that would have a huge impact, it would be to make the UK studio sector carbon neutral, including a complete switch to renewable power sources.

Whilst many studios, including Ealing and Cardiff's Wolf Studios, already offer renewable energy, the studio sector must go further, declares Albert. The scheme is currently in the final stages on a report with engineers ARUP and the BFI looking at reimagining the studio of the future.

Albert's head of industry sustainability, Aaron Matthews, says: "Film crews are limited on the meaningful carbon reductions they can deliver if the studios don't make changes themselves; for example, supporting production with waste repurposing. Feature films really need the studios on-board otherwise we are just nibbling around the edges.

"The UK is committed to going net zero by 2050 and government will focus on every industry in turn to achieve that. If we as an industry can say, 'Look, this is what we are doing', we will be setting our own strategy for achieving the target that works for our industry."

Pressure for film production to become green is also coming from the grass roots, with the formation of pressure groups such as Cut It, a crew-led action group which has tasked itself with uniting heads of department and crews with producers, actors and industry bodies to work out how to reform the industry from the bottom up.

"When we step on-set we leave our values at the door because there is this strong sense of the system as a monolith which nobody can change," declares DP and Cut It founder Sarah Cunningham. "But, I got to the point that I was no longer prepared to continue to go into the workplace compromising my values."

"At Cut It we are progressing by creating subgroups working on specific agendas. We aim to hold departmentally-specific branch meetings advised by environment experts in film production. They could come up with the five biggest things to change. Ideas created would feed into a climate summit - uniting HoDS and crew with established producers, top actors and industry bodies to establish how we can dramatically cut CO² emissions and waste.

"We would love it to be obligatory for all productions to have Albert certification including the US productions which come over to film in the UK. We think the US PGA system is less rigorous."

"The clock is ticking… the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says we have to cut emissions by 45% by 2030," says Cunningham. "For that to happen we need to lay the roadmap in the next 18 months and create a new normal. Once there is a critical mass of people saying 'We want change', nobody can really argue against that."