DIGITS & GLASS

Special Report / Cameras & Lenses

DIGITS & GLASS

Special Report / Cameras & Lenses

BY: Kevin Hilton

There is some irony that a magazine dedicated to the art of cinematography - a discipline founded on the medium of film - should have first been published as digital cameras were beginning to move into filmmaking. While it was not an overnight revolution, the new binary technology eventually took over from analogue celluloid as the first choice for image capture.

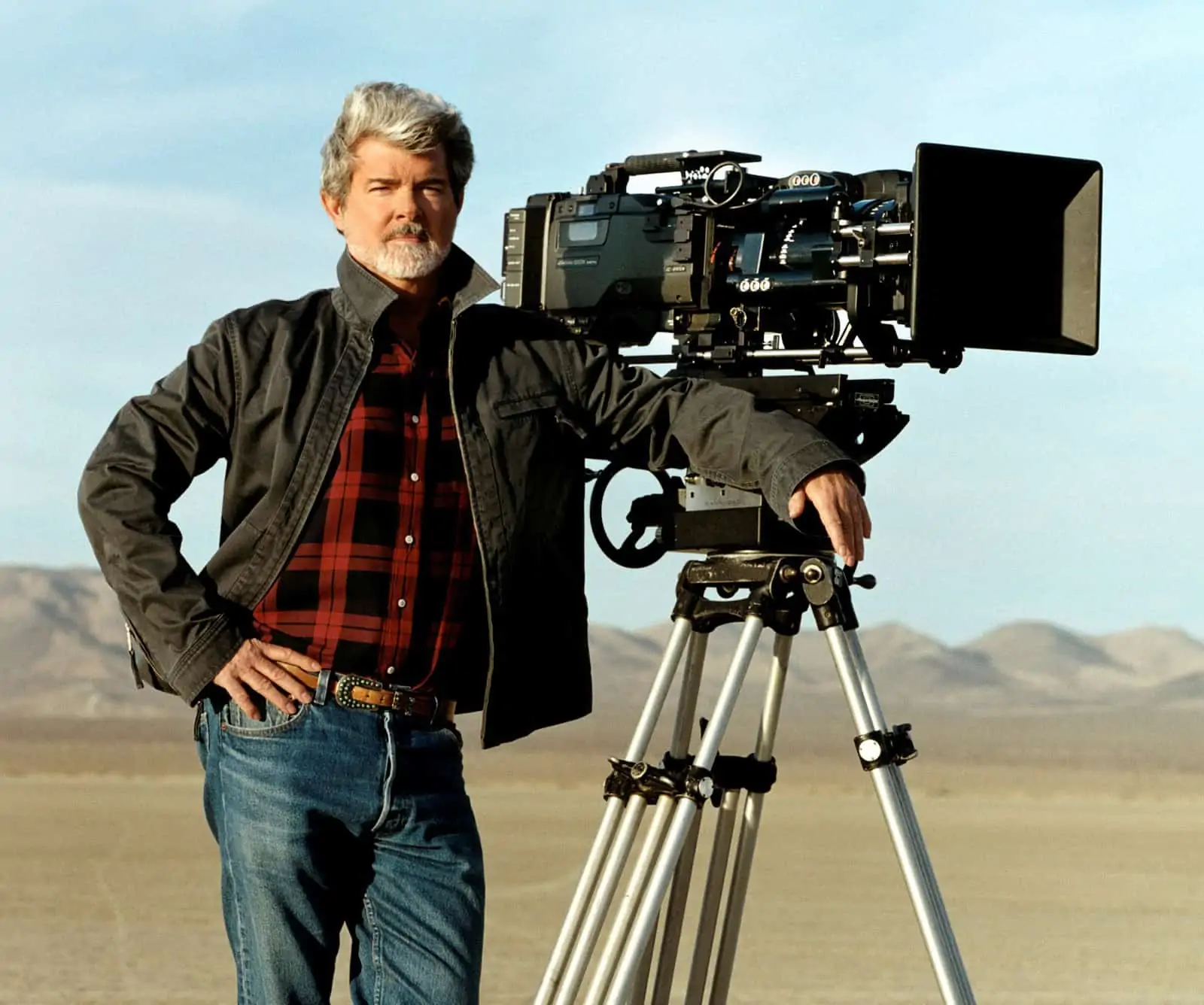

Attempts to break video into the film world came in the late 1980s, with Julia And Julia (1987, DP Giuseppe Rotunno AIC ASC) the first feature to be shot on the analogue Sony/NHK High Definition Video System. Sony continued developing HD acquisition formats, releasing the digital HDCAM range in 1997. This was aimed at TV but George Lucas, who was continuing his Star Wars story with a new trilogy, requested a digital camera with 24-frame shooting capability.

"To express the world of Star Wars VFX were necessary, so he approached us and that was the origin of the digital cinema camera with 24-frame capture and recording," explains Sebastian Leske, European Product Manager for news and cinematography at Sony PSE.

The Sony HDC-750 was used for visual effects on Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999, DP David Tattersall BSC), but the bulk of the film was shot on 35mm film cameras. The real change came with the second part of the story. Attack Of The Clones (2002) was captured, again by Tattersall, entirely in the digital domain using the Sony CineAlta HDW-F900, which had been introduced in 2000 as, Leske says, the world's first digital cinema camera. Sony has continued to develop camera technology and, in 2018, launched the 6K capable, full frame Sony Venice CineAlta digital motion picture system.

It was in 2002 that Lucas made his infamous "film is dead" prophecy, but that did not come entirely to pass. Even though digital has become the primary capture medium, it took most of the decade and more for it to reach that position, despite a flurry of development and new product releases in the early 2000s.

Film camera heavyweights Panavision and ARRI, like Sony, were keen to secure a share of the potential new market. Panavision began looking to the future in the late '90s by developing the digital camera that became the Genesis, which was eventually launched around 2004. Today, the 8K Red-based, Panavised, DXL2 is the company's flagship camera.

ARRI's move into digital came through its post-production division. "Our engineers gained a lot of experience in hardware through the ARRILASER digital film recorder and ARRISCAN film scanner," says ARRI managing director Franz Kraus. "It was then we decided to set up a small digital camera department to develop a new product."

This was run by the late Bill Lovell, previously with the BBC's film department, from ARRI Media in the UK. "Bill travelled the world and got a lot of input from our users as to what they wanted," recalls Kraus. The result was the ARRIFLEX D-20, released in November 2005. It was replaced by the D-21 in 2008, which in turn was superseded by the Alexa, now ARRI's core digital camera product line.

Thomson, which at the time owned Grass Valley, entered the fray with the Viper FilmStream. This appeared in 2003 and, after being used on many commercials was adopted by some filmmakers, notably David Fincher, who used it for both Zodiac (2007 DP Harris Savides ASC) and The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button (2008, DP Claudio Miranda ASC).

The burgeoning market attracted newcomers, including electronic imaging component developer Dalsa. Its product was the Origin, the first commercially available camera to capture at 4K, which was seen at the 2003 NAB Show in prototype form but did not become widely available until 2006. It was used for VFX on Quantum Of Solace (2008, DP Roberto Schaefer AIC ASC), but in the same year as its release Dalsa discontinued the Origin and shut its Digital Cinema division.

However, the newcomer that did sustain is Red Digital Cinema, established in 2005 by Oakley eyewear and apparel company founder, Jim Jannard, a billionaire who professed a passion for cameras. A prototype of the Red One 4K camera was seen at the 2006 NAB and IBC shows, although there was initially some cynicism as to whether the camera would ever become a reality.

This is something that Jarred Land, who joined Red Digital Cinema in 2006 and is now company president, acknowledges: "We came into the camera world fresh-eyed with no history other than our own experience of being shooters ourselves. That lack of cemented legacy along with the fact that we didn't actually know the rules made them a lot easier to break - 4K was an obvious one and it was the same with 8K and the shape of our cameras and the formats we shoot."

Red's approach, says Land, was to be respectful to film by offering 4K as a 35mm equivalent, with a codec that allowed the compressed image to be manipulated in a more flexible way. Although Land claims there were "far more cinematographers who understood what we were trying to do, giving not just Red but digital a second look", there was still resistance, if not mistrust, of the new medium.

This was certainly true of many older cinematographers. Some in the younger generation were also sceptical and not fully-prepared for the change digital would bring. "I didn't see it coming," Ben Smithard BSC recalls. "Everything was still 35mm, with some 16mm, during most of the 2000s. I was also doing a lot of TV and that was still film. The first digital system I was aware of was the Panavision Genesis, which I did some tests on. I thought that cameras would be the last thing to go digital, but it all moved quite quickly"

Today the comment commonly heard from cinematographers about their latest production, is that "it was always going to be digital". Whilst there is still affection for film and recognition of its qualities, most DPs are now of what Zac Nicholson BSC GBCT has called the "Roger Deakins school of thought": "You've got the quality of image and you can sleep at night and not worry about the rushes."

Franz Kraus at ARRI observes that digital was not meant to replace film but be used primarily for effects. The real driver, he says, which changed the landscape completely was 3D. "That was a remarkable time," he says. "There were higher budgets and the films were very successful. But film itself was out of the question in theatrical releases."

The late 2000s stereoscopy boom is now a distant, strange memory, although it prompted respected figures such as Jeffrey Katzenberg, chief executive of DreamWorks Animation, to claim that 2D films would become a thing of the past. Many established directors embraced the revitalised technology, including Martin Scorsese and James Cameron, who used the 3D Fusion Camera System from Pace HD on Avatar (2009, DP Mauro Fiore ASC), incorporating Sony HDC-F950, and later Sony HDC-1500 HD, cameras, plus Fujinon lenses.

As 3D faded away, the growing interest in higher picture resolutions - moving from 4K to 6K and, more recently, 8K - guaranteed the position of digital cameras in filmmaking. As well as the top-end, the new breed of DSLRs - notably the Canon EOS 5D - was adopted for independent and smaller budget shoots, as well as B and C-camera on larger productions.

Television drama also shifted to digital as transmission went HD and S16mm fell out of favour. This brought a latecomer to the party in the form of Panasonic's VariCam 35. This developed from the company's VariCam camcorders, which had proved hugely popular in natural history filmmaking. The breakthrough came with getting the VariCam 35 on the first series of BBC drama Doctor Foster in 2015. Since then it, like many other digital cameras, has benefited from streaming services such as Netflix specifying drama in 4K and higher. Another relatively late entrant to the market was Blackmagic Design with its Cinema Camera, introduced in 2012.

For a time, the discussion over digital cameras took attention away from lenses, which previously cinematographers had always considered more important than the box they went on the front of. But as new cameras appeared, with higher resolutions and bigger sensors, the lens design came under scrutiny.

"Lenses were massively under-specified," comments Marc Cattrall, market development manager at Fujifilm UK. "We brought out the Premier zoom at the beginning of digital and have seen the move from smaller sensors to larger ones. Things have moved on and now we're looking at spherical for widescreen."

Dan Sasaki, VP of optical engineering at Panavision, observes that high-performance digital cameras had many influences on lens design, including accommodating 3-chip technology, near telecentric design optimisation to compensate for additional optics within the cameras.

"As cameras migrated to single-chip sensors and the diagonals started to get larger, the lenses and their designs started to favour the digital momentum more than traditional requirements dictated by film lens/film camera combinations," he says. "We were no longer bound by a spinning mirror as an immediate obstruction for the optics, and we could extend the depth that the optics could protrude into a camera."

One manufacturer, in particular, is seen as bringing about a re-evaluation of lenses and what they needed to do. "Red was the catalyst," says Sundeep Reddy, a former cinematographer who worked at Red and is now regional manager for cinema products (Europe) at the Zeiss Group. "When Red jumped from 4K to 5K the sensor was larger and 35mm glass wouldn't cover it."

Les Zellan, Chairman of Cooke Optics, also points to the part the Red One played in what he calls "the digital revolution". Cooke introduced the Red Set of S4 lenses with Red numbers, which moved the company beyond the film world.

"Digital also expanded the market but although it's a wonderful format it is boring and sterile," Zellan says. "It needed something like the S4 to take the edge off the video and make the picture more cinematic."

The need for a filmic look led to renewed interest in vintage lenses, with Anamorphics also undergoing a renaissance. Lens developers have at the same time embraced the new technology of metadata, which makes all settings readily available throughout the workflow.

An early example of this was the ESC box, developed by Fujinon at the request of the ubiquitous George Lucas for Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge Of The Sith (2005, DP David Tattersall BSC). This rather cumbersome box automatically calibrated lens positions and enabled functions such as automatic back focus. Today intelligent lens systems, such as Cooke's /i and Zeiss eXtended Data, are standard issue and play an important role in keeping track of all information relating to a shoot.

Which, combined with the developing technologies of digital and HDR, continue to give cinematographers the freedom and flexibility to make the best looking images they can.