ELECTRIC DREAMS

A sparky HETV reimagining of Naomi Alderman’s award-winning speculative novel, The Power, subverts gender dynamics with an electrifying twist. We speak to three of the show’s DPs – Ollie Downey BSC, Ruairí O’Brien BSC ISC and Carlos Catalan – about their work.

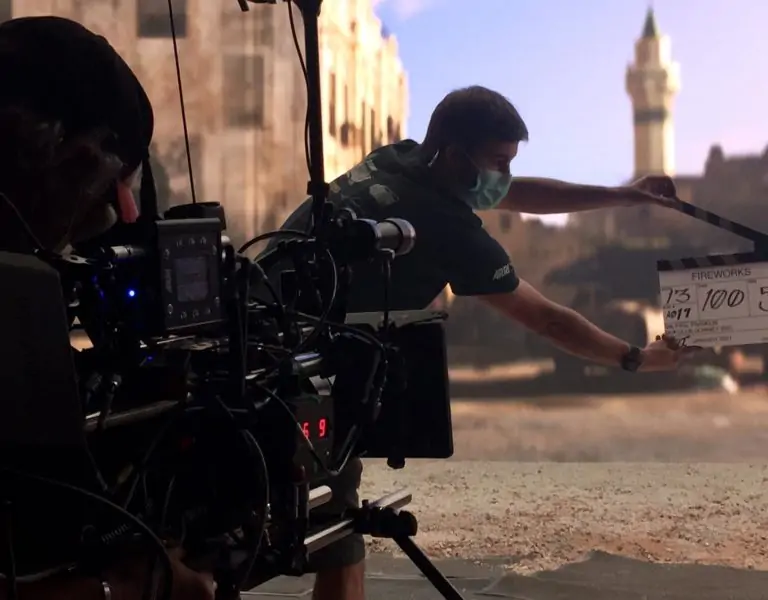

In a rather literal bolt from the blue, women suddenly find themselves armed with the ability to electrocute at will in The Power, the small-screen adaptation of Naomi Alderton’s 2016 Women’s Prize-winning novel. Its nuanced web of plotlines, locations and characters – including a Seattle mayor and her family, a Nigerian video journalist, and a troubled foster child in the Bible Belt – lends the sci-fi story perfectly to an episodic format, with no sacrifice in scale.

The Amazon Studios and Sister production’s journey to the screen has been as charged as its scripts, it seems. Production kicked off before the pandemic in 2019, with Reed Morano ASC and Colin Watkinson BSC ASC as block one director and DP respectively; in 2022 Deadline revealed the pair had departed the project, along with then-stars Leslie Mann and Tim Robbins. Toni Collette and Josh Charles later stepped into Mann and Robbins’ shoes for reshoots, while Raelle Tucker joined as showrunner. Despite the personnel fluctuations, the result is a glossy homage to Alderton’s writing.

“They were the best scripts I’d ever read,” admits Ollie Downey BSC, who was put forward for The Power by director Ugla Hauksdóttir. “They had this amazing, global scale and felt so ambitious. They also felt incredible timely; despite #MeToo and all the good intentions that came out after, there was this idea of, could [gender dynamics] have ever really changed?”

Block two DP Downey ended up devoting an unheard-of 18 months to the project. Shooting for his episodes – two, three, five, six and part of seven – began in March 2021 in London and wrapped in South Africa in late 2022, sandwiching a foray in Canada too. Also lending their lensing expertise to the show were DPs Ruairí O’Brien BSC ISC, Carlos Catalan and Giulio Biccari.

“Ugla and I were on and off together for a period that you’d never normally work with a director for,” Downey says. “It was a really good relationship and it just got stronger. The relationship is going to go one of two ways over that length of time because it’s such a stressful environment, but she was incredibly calm, great with the cast, and a pleasure to work with.”

Sensitive interpretation

Morano and Watkinson set the look for the series, which Downey describes as a “poetic, sensitive interpretation” of The Power’s world. This sensitivity included shooting handheld where possible and creating intimacy with the characters by using JDC Xtal Xpress lenses, which fall apart when shot wide open. “You get all these beautiful ‘happy accidents’, so it was about embracing those imperfections,” he adds.

Ruairí O’Brien echoes Downey’s approval. “I loved shooting on the old Xtal Xpress lenses. They are so beautifully distorted on the edges that even the simplest image becomes alluring in a way that I don’t think audiences will understand. They hopefully will find the pictures seductive in a subconscious way.”

The Xtal Xpresses were teamed with the Sony Venice, with its 6K sensor capacity, to deliver the 4K end product. It was Downey’s first time shooting with that model, but he was pleased with its capabilities. “I really enjoyed it. I think the dual sensor, with the 2500 ISO and 500 ISO, is a really useful tool,” he adds.

The team didn’t use any filters, but they always shot without matte boxes which provided a softening effect. “Even when we weren’t aware of it, we were often getting this very subtle veiling flare which was softening the image,” Downey says. He highlights the need for excellent focus pullers when shooting with the Xtals (A-camera focus pullers were David Agha-Rafei in London, Tim Spencer in Canada and Diogo Domingues in South Africa).

References for The Power’s visual language ranged from Terrence Malick, for his iconic ‘magic hour’ shots, to Yorgos Lanthimos, for his irreverent style and penchant for wider lenses.

Global story

“One of the key takeaways from the project is that it was a global story, and the local teams all brought something unique to the project,” says Downey. “Wherever we went, we embraced the local way of working – as you should.”

Locations across South Africa including Durban, Grabouw, and Cape Town’s Camps Bay, were shot for Nigeria, South America and the Middle East. Inspired by Reed and Colin’s work, and their references to Terrence Malick, Downey and team tried to shoot ‘magic hour’ and dusk when possibly. “It’s a really tricky thing to do on a (six pages a day) TV schedule,” he notes. “You need a confident director, the cast need to be onboard with the idea and you need a top-notch crew. Whether it was shooting dusk at Frensham Ponds in the UK, a sunset scene overlooking the water in Camps Bay in South Africa, or shooting Toni Collette and John Leguizamo on a pier in Port Moody Vancouver, it was a great buzz – as close to a live theatrical experience as it gets for a film crew.”

Meanwhile, the London shoot included a stint in an LED volume at the ExCeL in East London for the Seattle driving scenes. For a recreation of a 1980s Eastern European gymnastics championships in episode two, the team found the perfect location in the form of the Crystal Palace Sports Centre, transformed by production designer Sonja Klaus. Downey and his team captured the vintage vibe of the competition by shooting open gate spherical on heavily diffused, 20-year-old broadcast zooms. With only around 50 extras able to come on set due to COVID restrictions, they had to shoot various plates around the hall across a fun couple of days of filming.

The location that proved the most challenging for Downey was one of the Vancouver spots: the Cleary-Lopez home where Toni Collette’s mayor character lives with her family. “It was the middle of summer, it was south-facing, and just dropped down to the water,” he recalls. “There was no real way of controlling the sun or getting the lights around, and we were in these rooms with floor-to-ceiling windows for a couple of weeks. We had to just go with it because it was so beautiful, and it required us to be quick and nimble.” He credits his local grip team, led by Kim Olsen, for their support in pulling off these scenes.

O’Brien recounts the challenges of the reshoots from a location perspective. “I had to pick up a new ending for a scene that Colin Watkinson shot with Reed Morano,” he recalls. “They originally filmed it in London, and we were asked to complete it in Vancouver. The closest matching location they offered us was really just a street corner. Panning left or right revealed the gag. So, we had to shoot everything towards the same wall. When you see the cut, I don’t think it’s noticeable at all!”

One of the trickiest scenes for Carlos Catalan was at the end of episode seven, where everyone goes into the sea for Allie’s baptism. He and his team had more than three pages to shoot and knew it was going to be impossible to achieve that in 20 minutes of downtime. “It was also a logistically complicated scene as we had 12 cast in cold water, water safety crew, we had to protect cameras, getting the crew in dry suits, calculate the tide levels and so on,” Catalan explains. “As we had a few night exterior shoots I suggested to the first AD that we could get into the water at the beginning and at the end of each night for three consecutive nights. I got a straight answer: ‘Are you crazy?’ It took me some time to develop that idea and convince him it was the best possible way to achieve that scene that was the end of the episode. Miraculously, after talking to the producer, we managed to get two dawns and three dusks, which was enough to achieve the scene.”

Bright and beautiful

Lighting the South Africa scenes followed the original block one crew’s approach, revolving around an “old-school” tungsten package with Dinos and Wendy lights, which worked well in tandem with the Xtal Xpresses. “We had these big tungsten sources outside windows and edged them with the lens, so you would get those beautiful warm flares,” says Downey. Canada and London, meanwhile, were more HMI and LED-led.

Lighting up Central London’s Senate House was also tricky in terms of getting machines in and general light logistics. “Our gaffer Charley Cox was very clever at positioning lamps on roofs quite a distance away, then bouncing them off other walls and roofs to get soft pushes through windows. So, it wasn’t the most lighting friendly location, but it was a good challenge. And [Charley and his team] did a brilliant job.”

“Often it’s the small scenes that are trickiest,” adds O’Brien. “Lighting big spaces involves big sources far away. We had a bedroom at night and it’s the same old issue where the script says it’s very dark, but it also describes actions we need to see. Those things are contradictory and then as the actress moves around and the camera moves it becomes trickier to make it feel convincing. A small room at night can sometimes be much trickier than a massive stunt.”

Following the change in showrunner, the original show LUT was switched for a brighter, more saturated look, with Tim Drewett from Warner Bros. De Lane Lea working on the grade. Most scenes were shot practically, with as little blue screen as possible, and Union VFX and LenscareFX assisted on the effects side as needed.

Cross-block collaboration

It’s clear The Power was an unusual challenge in its scope for both its cinematographers and its wider cast and crew. “As a life experience, it was unlike any other job,” Downey says, reflecting on the shoot.

“Because of COVID and shooting on three continents, double banking and so on, I think I worked with eight gaffers and about a dozen operators, five DITs and about 40,000 camera assistants,” jokes O’Brien. “That became a challenge of its own.”

What was especially interesting to the DPs was how they were able to collaborate with the other cinematographers over the shoot as a result of the pandemic and personnel-related workflow interruptions. “Normally you have a block and everyone’s very protective over their work, but when the new showrunner came in, all the storylines were mixed up,” Downey explains. “So, no-one shot 100% of any episode. Then, when I got COVID, Carlos jumped in and shot for me for three days, and when he got COVID I did the same.”

“I found it really interesting being able to see how we would each approach things slightly differently. It was a great way to learn,” O’Brien adds.

Downey sums up that feeling of collaboration that made the shoot so special: “It was that sense of all being in it together. You get that with a crew that all get on. It’s a lovely thing, that camaraderie – like being in a band or a sports team as a kid. Well, we had that for 18 months which made it all the more special.”