ANGLING FOR SUCCESS

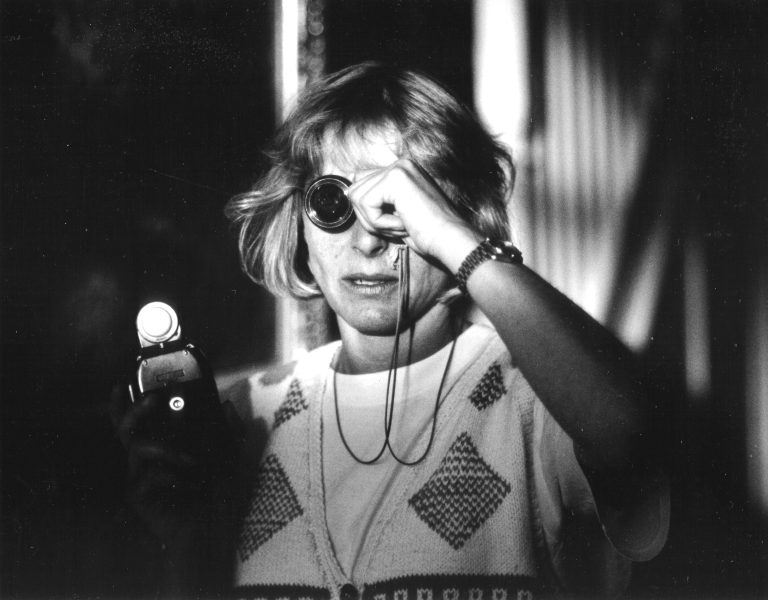

Our cinematographic journey through the BSC’s history, courtesy of the Society’s Preserving the Vision book, continues with Oscar-winning founding member Robert Krasker BSC.

Revered for his iconic, Oscar-winning work on The Third Man (1949, directed by Carol Reed), Robert Krasker BSC was born in 1913 in Alexandria, Egypt. The youngest of five children from a Romanian father and Austrian-born mother, Krasker’s family moved to Perth and his birth was registered in Western Australia.

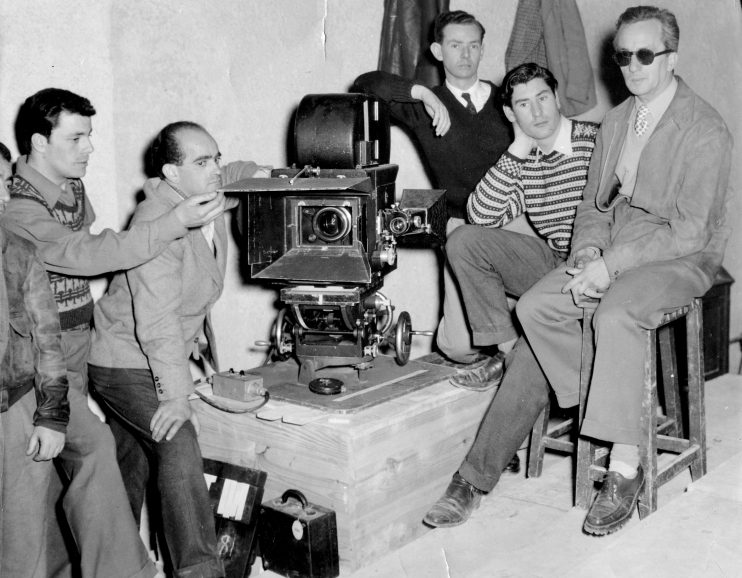

In 1930 he sailed for Europe to study art in Paris and optics and photography in Dresden, Germany. He worked with the cinematographer Philip Tannura ASC at Paramount’s Joinville studios in France, before moving permanently to London in 1932. Joining Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions as a camera operator, he assisted the studio’s chief cameraman, Georges Périnal BSC, who had a crucial influence on Krasker’s subsequent development. From Périnal, he absorbed lessons in lighting, composition and camera placement, putting them to use in his best work in the 1940s and beyond.

Sometimes credited as Bob Krasker, he worked on such major productions as Rembrandt (1936) directed by Alexander Korda, Things to Come (1936) directed by William Cameron Menzies and The Thief of Bagdad (1940) directed by Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell and Tim Whelan all of which were photographed by Georges Périnal, who won an Oscar for the last in the list.

He caught malaria in the Sudan while working on The Four Feathers (1939) directed by Zoltan Korda and again photographed by Georges Périnal BSC and became diabetic. Promoted to associate-photographer, he worked on One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942) directed by Powell and Pressburger and photographed by Ronald Neame CBE BSC. His first solo credit was for the wartime propaganda film The Gentle Sex (1943), co-directed by Leslie Howard and Maurice Elvey. As a result, Laurence Olivier hired him to shoot his Henry V (1944) in 3-strip Technicolor.

By this time, Krasker was considered among the front rank of cinematographers. The next year he shot the iconic and much celebrated Brief Encounter. Based on a stage sketch, scripted by Noël Coward and directed by David Lean, the film was as sensitive and small scale in black-and-white as Henry V was epic and celebratory in colour. Krasker was equally accomplished in both genres. His association with Lean ended when the director fired him from Great Expectations (1946), claiming that his work was ‘too polite’ and that he wanted something `harder’.

With Odd Man Out (1947), the first of four films made with Carol Reed, Krasker began the most artistically rewarding partnership of his career. It reached its apogee with The Third Man (1949), scripted by Graham Greene, in which Krasker’s atmospheric use of unusual perspectives, wide-angle lenses and a tilted camera helped to win him an Oscar for black and white photography in 1950.

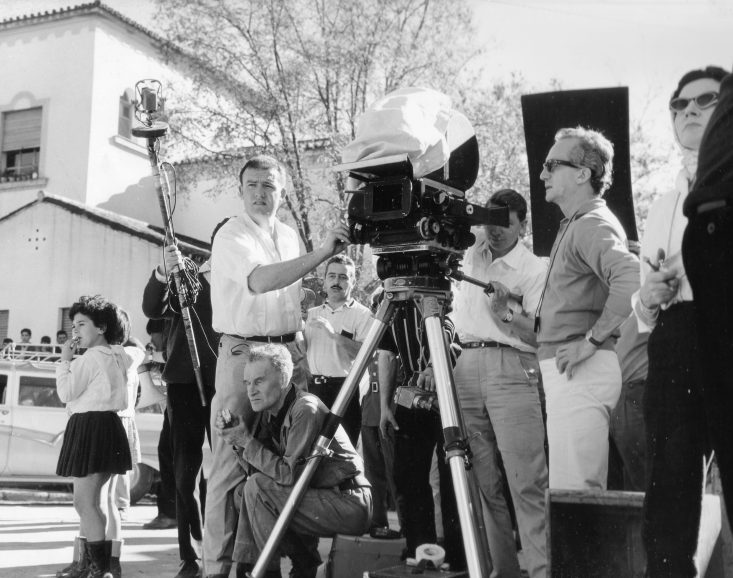

His style, eschewing glamour in favour of realism and employing high-contrast images and unconventional compositions, is timeless. It is particularly evident in the series of epic spectacles with which the final phase of his career is mostly identified. Robert Rossen’s magisterial Alexander the Great (1956) and a succession of large-scale films for the director Anthony Mann including El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), demonstrated Krasker’s art at its most confident and mature. He also photographed Senso (1954) for Italian director Luchino Visconti.

Unhappy with the cinematic trends of the late 1960s and struggling with health problems, Krasker virtually retired after The Trap (1966) directed by Sidney Hayers. He had worked with some of the great directors of his time, including John Ford, Joseph Losey, William Wyler, Anthony Asquith, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Michael Powel and Emeric Pressburger, Luchino Visconti and Peter Ustinov.

His career was briefly resurrected in the late 1970s when director Hugh Hudson was looking for an experienced black and white cameraman to shoot a beer commercial in the style of wartime magazine The Picture Post.

His colleagues remember him as an unassuming, modest man, gregarious despite superficial shyness, and easy to work with. If unsure of a technicality, he was never too proud to consult his junior assistants.

He attached so little importance to worldly fame that his Oscar statuette served as a doorstop in his home. A gifted linguist, he was fluent in French and had a good working knowledge of Spanish and Italian. He died of complications from diabetes on 16 August 1981 at home in London. [With thanks to Joel Greenberg, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University].

His other credits include Bonnie Prince Charlie, Cry, The Beloved Country, The Quiet American, Billy Budd, The Running Man, and The Heroes of Telemark. Along with his Oscar win, his selected awards include a BAFTA nomination for The Running Man (1964, dir. Carol Reed); BSC Best Cinematography for Romeo and Juliet (1954, dir. Renato Castellani); and BSC Best Cinematography for El Cid (1961, dir. Anthony Mann).

Preserving the Vision

This piece was adapted from the book, Preserving the Vision. Compiled and edited by Phil Méheux BSC and James Friend ASC BSC, the book celebrates the history of the British Society of Cinematographers along with biographical details of every member since its inception in 1949 plus listings of their awards and notable credits.

The book can be purchased from the BSC by contacting Helen Maclean at helen@bscine.com. All profits will benefit the Film & TV Charity.