FOREVER YOUNG

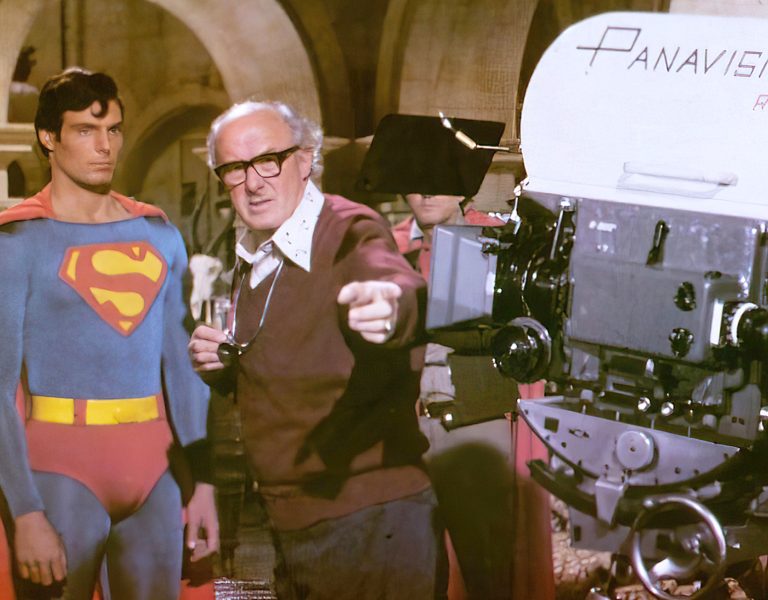

Freddie Young OBE BSC’s lens has woven cinematic epics resonating through generations, spanning from Lawrence of Arabia to Doctor Zhivago, amidst the tumult of two world wars .

Fascinated by films as a child, Freddie Young OBE BSC went to the cinema at least twice a week. He also swam at Lime Grove swimming baths which happened to be opposite a vast greenhouse of a building belonging to Gaumont-British Picture Corporation. In 1917, aged just 15, Young knocked on the door and asked for a job. Because most workers had been sent to fight in the First World War, he was immediately taken on in the laboratory, which he considered the best possible training for a cameraman. By 1919, Young was lab manager and after it shut down, was made assistant cameraman and general assistant, even volunteering to fall 50 feet from a castle wall into a sheet on Rob Roy (1922), for which the director, William Kellino, rewarded him with 10 shillings (50p).

During the 1920s he worked on newsreels, including an elaborate recreation of the Battle of the Somme in documentary style, as well as Victory (1927 d. M.A. Wetherell), set in the last weeks of the First World War. At the end of the decade, he was working for Hitchcock on Blackmail (1929), Britain’s first ‘talkie’, creating the elaborate series of in-camera dissolves for the montage which opens the silent version of the film.

Later, Young teamed up with director Herbert Wilcox, which resulted in some memorable pictures including Goodnight Vienna (1932), Bitter Sweet (1933), Nell Gwyn (1934), Victoria the Great (1937) and Sixty Glorious Years (1938) all starring Anna Neagle, whom Wilcox had married.

After 65 feature films for Gaumont-British and with the Second World War in full swing, Young photographed the U-boat drama 49th Parallel (1941) for Michael Powell and shortly after, became a Captain in the British Army and chief cameraman and director of training films for the Army Film and Photographic Unit.

He was invalided out of the war in 1943 and became chief cameraman at the newly opened MGM Studios in Borehamwood (formerly Amalgamated Studios). There he photographed films including Ivanhoe (1952 d. Richard Thorpe), for which he was Oscar-nominated, the studio work for John Ford’s lavish safari film Mogambo (1953) and Britain’s first CinemaScope film Knights of the Round Table (1953 d. Richard Thorpe).

Lean machine

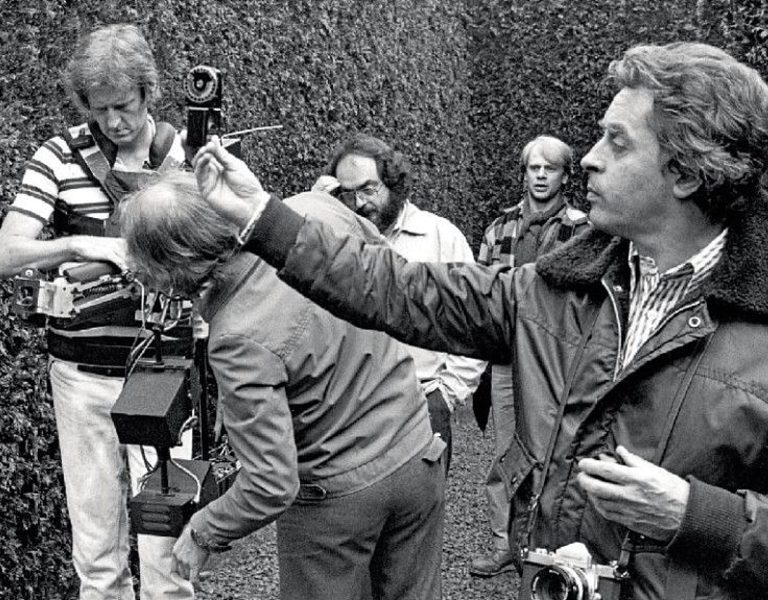

He left MGM in 1959 due to budget issues, became freelance and was immediately snapped up by Sam Spiegel and David Lean for Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Lean and Young had first met on the film Major Barbara (1941), adapted from the play by George Bernard Shaw. During that shoot, Lean, a relative novice at directing, gave Freddie some terse instructions to which Freddie replied, “Don’t teach your grandmother to suck eggs.” This stuck in Lean’s memory, and years later he was still wary of hiring Young for Lawrence of Arabia until no other cameraman of repute was available. Young arrived on location, marched up to Lean and said, ‘Don’t teach your grandmother to suck eggs.’

From an inauspicious beginning, David Lean and Young formed a partnership. “He gives you an inspiration,” said Young, “so you go out of your depth and try and do something extraordinary.” Lean had a passionate concern for the visuals, but he knew that Young, of all cameramen, was equally passionate. The shot that has aroused perhaps the most comment is the ‘mirage’ shot of Omar Sharif riding towards camera. On a visit to Panavision Hollywood to order equipment, Young saw a 450mm lens with no focus markings sitting on top of a cabinet and decided to take it with him, ‘you never know when something may come in handy when you are deep in the desert.’ It was this lens that was used for the famous shot.

For Lean, Young photographed not only Lawrence of Arabia but his own personal favourite Dr Zhivago (1965) (replacing Nic Roeg CBE BSC who had been ‘let go’) and Ryan’s Daughter (1970); winning an Oscar for each. He also photographed Lord Jim (1965 dir. Richard Brooks), Battle of Britain (1969 dir. Guy Hamilton) and Nicholas and Alexandra (1971 dir. Franklin J. Schaffner) for which he was nominated for another Academy Award. Aged 83, his last credit as cinematographer was for Invitation to the Wedding (1985 dir. Joseph Brooks), starring John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson.

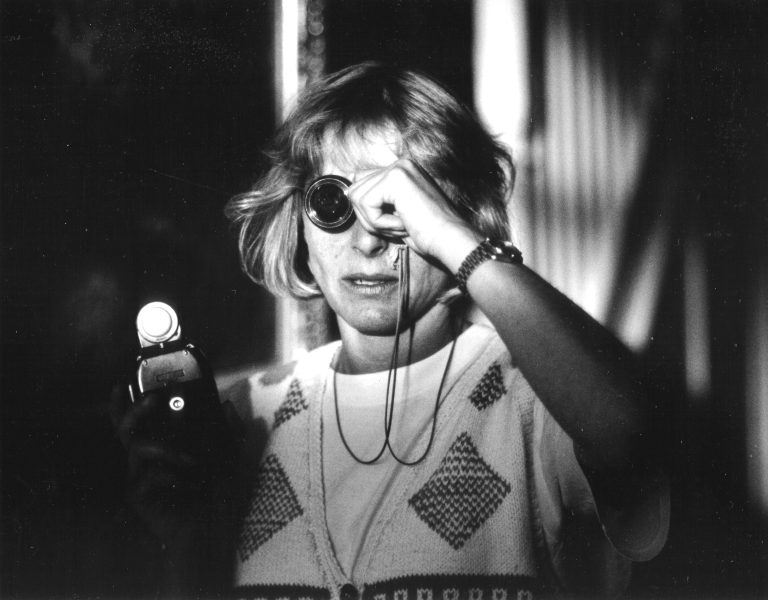

Before he retired, Young had one directorial effort, Arthur’s Hallowed Ground (cin. Chic Anstiss Assoc. BSC) which he made for television in 1985.

Young was an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Fellow of the British Kinematograph Sound and Television Society and at one time a member of the American Society of Cinematographers.

Young’s additional credits include:

Goodbye Mr. Chips, (1939), Nurse Edith Cavell (1939) The Winslow Boy (1948) Treasure Island (1950) Lust for Life (1956), The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1957), I Accuse! (1958) Indiscreet (1958), The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), The Deadly Affair (1967) and You Only Live Twice (1967).

Young’s other awards include BSC Best Cinematography 1965: For His Contribution to the International Recognition of British Cinematography.

Young garnered several nominations, among them one Oscar for Nicholas and Alexandra (1971 dir. Franklin J. Schaffner) and a BSC Best Cinematography Nomination for Bhowani Junction (1956 dir. George Cukor). He was also nominated for a BAFTA on three occasions: The 7th Dawn (1964 dir. Lewis Gilbert), Lord Jim (1965 dir. Richard Brooks) and The Deadly Affair (1967 dir. Sidney Lumet). In addition, Young secured a BSC Best Cinematography Nomination for Bhowani Junction (1956 dir. George Cukor).