Into the blue

When an aeroplane crash-lands in the Pacific Ocean, the clock is ticking for its passengers in claustrophobia-laced survival thriller No Way Up. Trapped in an air lock and circled by sharks, will any of them escape before the plane makes its final descent – into a bottomless gorge?

With so many varied and exciting elements – including underwater and virtual production work – to the project, No Way Up was too enticing to pass on for director of photography Andrew Rodger (Three Day Millionaire, Plebs). “Sure, it was quite an ambitious project, but as a cinematographer it was fascinating,” he enthuses.

On board to direct was Swiss filmmaker Claudio Fäh (Wilder, Child of the Earth), whose previous work as a visual effects supervisor meant he had a wealth of technical expertise to draw on. This meant he was very easy to work with for Rodger: “Given his experience, it could have gone either way, but it went the right way with him. He is very collaborative and a genuinely lovely person who was very well liked on set – and I think it shows in the film.”

Over a month’s prep, Rodger set about establishing the look and dynamics of the film with Fäh. “In the very first conversation I had with Claudio and the producers, we settled on anamorphic,” the DP recalls. “There was a wish from their end to make [the film] as big and cinematic as possible for the budget, and I really liked that. For me, I wanted it to be as filmic, dramatic and lush as possible. There are a lot of action sequences at the beginning, where people are pulled out of aeroplanes and flying around, and it’s a balance of making sure it’s very clear to see what’s happening in the chaos, but also giving it some kind of style and drama.”

DIT: Chris Tilley (top); video assist: Andrew Wain (bottom); focus puller: Karl Hui

The scenes deep in the Pacific Ocean lent themselves to a darker, moodier feel. He references the James Cameron film The Abyss, another underwater thriller: “I’d recommend anyone who is about to make an underwater film to watch the behind the scenes – they’re frightening but eye-opening.”

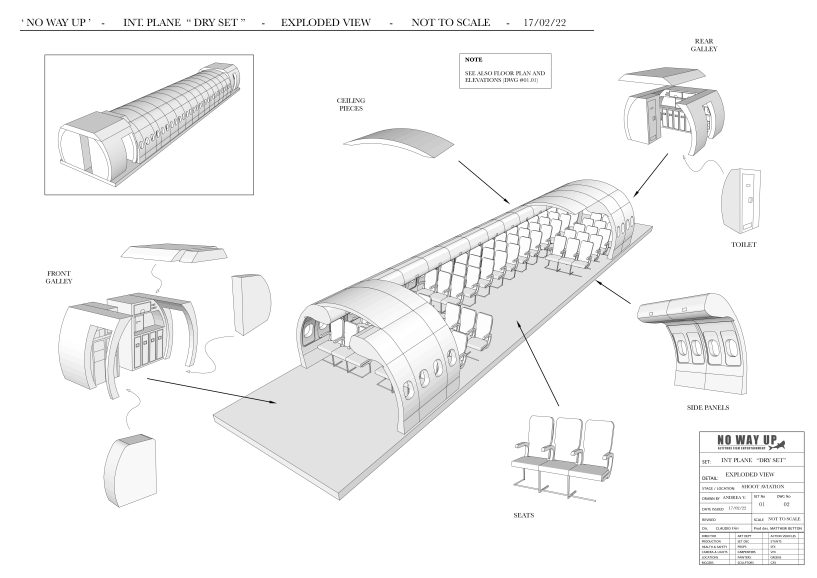

Meanwhile, the art department had been hard at work crafting the intricate set. Production designer Matthew Button and his team had made scale models of the sets, which included the ‘wet set’: an aeroplane fuselage submerged in a water tank that could be lifted up and down on a motor-powered rig, where most of the film would take place. The water tanks were located in Basildon, while airport scenes were captured between Stansted and Southend Airports in the UK, and RD Studios were used for virtual production.

Rodger chose the ARRI Alexa LF and LF Mini with Caldwell Chameleons, which he used to achieve a full-frame anamorphic image, from 24/7 Drama. “It was a big thing for me – I wanted that almost medium format feel, really separating the actors from the backgrounds and not going out of focus,” he says. “We’re spending a lot of time in one place – on a plane – and it would be quite easy to be distracted by a big white bulkhead behind the whole time, so it was important to have that shallower depth of field when I needed it. The Chameleons were small and all a uniform size which saved precious time when working with the underwater camera rigs. Thanks to DP Ben Spence who made me aware of them.”

Another aspect of the lenses that Rodger loved was the “classic, ‘70s’ Panavision” flare. “I think it adds to the ’80s blockbuster mood,” he adds.

It was largely a one-camera shoot, with a few days of two-camera work with Nathan O’Kelly operating B-camera and Steadicam. While Rodger operated on most of the above-water scenes, he enlisted specialist operators Mark Silk and Rich Stephenson, and specialist 1st AC Rob Hill for the underwater sequences, with marine safety and co-ordination from Marine Department.

“It was very, very safe,” the DP says of shooting in the waterlogged fuselage. “It wasn’t completely underwater – I was able to swim around but if it did get submerged, I had a regulator. The plane had breakaway panels on the top of the roof so if anything went wrong, we could push them out. If there was ever a problem, we had safety divers hidden away from the camera who could come in.”

One of the key challenges with the lighting was showing how it shifts over the course of the film – not just from day to night, but as the plane slips deeper into the ocean. Rodger explains: “A lot of the interior light for the underwater scenes was coming from two LED strips on the floor. They were RGB so we had control over the colour of those as well. The lighting approach meant that there was never anything inside the fuselage of the plane – everything came from the outside – unless it was an environmental light. Keeping all the electrical equipment away from divers works safety-wise as well, but I think it helps make it feel more real.”

Rodger also used colour gels and lamps to achieve an underwater feel through the plane windows. “Most of the time, the plane was half-submerged in the water tank. This meant that the last six rows of windows looked out above water level. In order to see the illusion of the air pocket we gelled the windows with frost and backlit them from the shore with LED lamps, tuning the colour by eye to match the windows that were underwater.

“As for the underwater section of the plane, we used gaffer Bernie Prentice’s custom-made waterproof 6ft LED tubes in the tank outside the fuselage. These were daylight and then gelled with 1/2CTB. Combined with the practical LED floor strips inside the plane, everything was dimmable from a lighting desk.”

He could also rely on the expertise of Prentice, whose extensive gaffing work both above and below water includes The Little Mermaid, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, and Kingsman: The Secret Service. “This was one of the most enjoyable films I’ve ever worked on,” said Prentice. “Safety was a key concern on set. I worked closely with Claudio, Stuart [Cadenhead, first AD] and Andy. We all worked hard to ensure a safe set for all involved. All films are about crew and people. It’s always a pleasure to work with nice ones!”

Although some VFX work was necessary, the filmmakers aimed to work as practically as possible. “From a filmmaking point of view, I think it feels more realistic, but it’s also budgetary,” Rodger notes. “It would add hundreds of VFX shots to greenscreen and track all of the windows in the aeroplane as it flew through the air, so we had to project that practically on set.

“We built 12 foot high screens either side, the length of the plane and covered them in Ultrabounce. Six projectors stitched together projected the moving sky outside. This meant we could shoot from any, height or angle inside the plane and not shoot off.”

As the plane set was static, any movement had to be created by the actors physically shaking the plane, as well as through camerawork and lighting. “That’s why there’s a lot of handheld and shaped physical shaking of cameras, to really show the turbulence. Bernie’s team worked with a dimmer board and with hands-on lamps to sell the effect.”

Rodger worked closely with colourist Gareth Bishop at Dirty Looks to develop a couple of LUTs to contrast the above-water scenes with those below. “The LUT was pushing everything bluey-green, and anything warmer would come really warm. Later in the film, you’ll see that anything orange is pulled forward and blue is pushed back. It was a way to make quite a confined space feel a bit more 3D and be easier to read.”

The DP is full of praise for the cast and his team, which also includes 1st AC Karl Hui and 2nd AC Nina Mangold, in pulling off the challenging shoot. “It’s given me a taste to do more complex things,” he says. “I loved the action and the complexity, and I loved being able to pull off these ‘magic tricks’ with the crew. It was really fun.”

Balancing the film’s challenges with ensuring a pleasant atmosphere on set impressed Rodger’s close collaborator, key grip Frank Corr. “Working almost entirely inside the aircraft fuselage, stunts, cameras, SFX, sound and lighting pushed out scene after scene without getting in each other’s way, not stepping on each other and with a smile,” he says. “We all like to work in an environment where we can do our best job and feel valued even when things aren’t going according to the vision.

“Claudio and Andy sent out family vibes from day one. Where appropriate, our input was always considered, discussed and implemented (or not!), but that gave us all a sense of ownership and pride.”