Mark London Williams kicks off 2025 with a deep dive into award-season contenders Nickel Boys and September 5, where personal narratives meet pivotal moments in history, along with a look at other hopeful contenders and Women In Media’s year-capping Holiday Toast, celebrating undersung Hollywood heroes.

*Hours after this column was sent in, our correspondent Mark London Williams drove to a screening, attempting to dodge flying palm fronds in the air on a day of record Santa Ana winds. By the time the film had ended, Pacific Palisades was on fire. By that evening, Los Angeles was undergoing its most calamitous modern natural disaster — perhaps already the most costly in California history.

Some twenty four hours later, the ASC Clubhouse itself was briefly imperiled when one of the many subsequent wind-whipped blazes erupted in the Hollywood Hills, some blocks away, though that fire was seemingly contained within a couple of hours. Had it occurred the evening before, with its frenzied winds, it is likely that much of Hollywood — including the Clubhouse — would be gone.

So while Mark here covers some award season contenders, Women in Media’s holiday toast, and other early calendar events, a palpable knife’s edge has now sliced through whatever facade of “normalcy” was left heading into 2025.

How this will play out in Hollywood in general, and through the award season in the near term, all remains to be seen. But we’ll have more on these too-historical moments next time.

—

“We’re a fierce group and nothing is going to stop us.” Thus, Women in Media’s executive director, Tema Staig, kicked off that fierce group’s annual Holiday Toast, once again held at the Sofitel Beverly Hills, located a short walk away from numerous talent agencies and across the street from the Cedars Sinai medical complex, thus accommodating various stages in a Hollywood life.

Though, of course, part of the Holiday Toast’s mission is to reflect and shine a light on some of those careers that contributed much to Hollywood itself but have been either undersung in recognition or too easily overlooked. This year’s honorees were makeup artist Geneva Nash Morgan (Star Trek: Insurrection, Planet of the Apes), first AD and exec producer Ellen H. Schwartz (The Princess Diaries, Pretty Woman), camera operator (and Emmy winner!) Helena Jackson, and production designer Jeannine Oppewall (L.A. Confidential, Pleasantville and a quartet of Oscar nominations!).

This publication is now one of WiM’s media partners (where we’ve covered Morgan’s husband and partner, routinely-Emmy nominated cinematographer Donald Morgan, ASC, in columns past) though it was Schwartz who observed that “when I started in this business, this room didn’t exist.” And the Holiday Toast has become another Hollywood road marker, kicking off not only the titular holidays, but the hurlyburly of award season, with its nominations, constant handicapping, and early critics awards shortly following.

Our first catch-up from this side of the pond since just before Thanksgiving, there’s a lot of terrain to cover. And more still to come in our next edition, which will have winners for both the Golden Globes and the first round of guild awards, as well as the Oscar nominees.

This go-round, we look at a couple of films that already have a firm footing in the nomination rondel, and a couple that also illustrate how hard it is – despite the breadth of award ceremonies held over all those L.A. winter weekends – to always include everything deserving of attention.

Amazon/MGM’s Nickel Boys, from director RaMell Ross, is one of the former, and like The Seed of the Sacred Fig and The Brutalist, looks at the way history (or histories, since, these films remind us, people experience shared moments through their own prisms) inevitably intersects with personal lives – defining them, twisting them perhaps, or even cutting them off.

Nickel Boys, from Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, is based on the particular history of the notorious Dozier School for Boys in Florida’s panhandle. Shuttered now, this “reformatory” turned out to be the site of wide-ranging abuse, physical, sexual, and otherwise – visited particularly upon its young African-American inmates. (As Whitehead noted in an earlier interview, the school’s survivors still meet with each other, years later – in part, it seems, to make sure the place is still shut.)

Renamed here the Trevor Nickel Academy, the film tells the 60s-era story of Elwood and Turner, who meet after Elwood, while hitchhiking to college classes, finds himself riding in what turns out to be a stolen car, and is eventually sentenced, despite having nothing to do with the theft. Full of Civil Rights-era ideals, he is convinced justice will finally prevail. His more street-savvy friend Turner, suspects – or knows – otherwise.

The film, already a best picture nominee for the Globes and Independent Spirit Awards, similarly scored an Indie Spirit nod for Jomo Fray’s startling cinematography work, made more so by director Ross’ decision to use shifting first person POVs between the two protagonists.

Both Fray and Ross have documentary backgrounds, and we asked Fray, in an email interview, whether that was how he came aboard this particular narrative project.

He talked about being “profoundly moved” watching Ross’ earlier doc, Hale County, This Morning, This Evening, saying it “was so deeply evocative that I felt I had to meet the people who had created these images, and when I found out the director was also the cinematographer that feeling merely doubled!”

Indeed, one of the particular themes this edition is DPs-turned-director (see our statement from Lajos Koltai ASC HSC below), so we asked Fray if the shared backgrounds led to a working shorthand between the two. “Being an image maker himself it meant that RaMell both thinks very deeply about the image and is very articulate on what constitutes it, which made for such an exciting collaboration… [and] also made it easier to build a joint language. Funnily enough, on set we rarely talked technically, but rather, conceptually or emotionally about what the image needed.”

Though before they’d even gotten to set, there was discussion about the POV approach that Ross was already leaning toward, having already done work that “grappled with the idea of authorship of the image. Although photographs present themselves as objective, was it possible to undeniably attribute a singular subjectivity to the image?” Reading Whitehead’s book made “a lot of those same questions bubble up,” Fray said, and eventually “RaMell and I stopped using the term ‘POV’ and started saying we wanted to build a sentient image—an image that was inextricably tied to a human body moving through space with a present-tense immediacy.”

And if there’s any phrase that sums up the film’s power, it’s “present-tense immediacy,” despite its historical setting, or perhaps because of the “present-tense” we’re all about to head through collectively.

As for the film’s toolbox, they “shot on the Sony Venice with the Panavision VA lenses (which were only prototypes at the time). For lighting we relied heavily on the Lightbridge CRLS system as well as Dedo’s E-flect System, Fiilex Fresnels, Astera Fixtures with Lightsocks, Creamsource Vortexes, Roscoe DMG units, and Litegear Spectrums. Our key grip Gary Kelso, and the team also built custom mounts for some of the body rigs and custom mirrors to create a more textured quality to the light. We shot most of the movie in a first person perspective and the ‘present day scenes’ (a flash forward in the movie) on a Snorricam rig attached to the character.”

Wikipedia’s Shorricam description is somewhat illuminating, describing it as a mount “rigged to the body of the actor, with the camera facing (them) so that they appear in a fixed position.. (presenting a) dynamic, disorienting point of view from the actor’s perspective, (and) an unusual sense of vertigo for the viewer.”

A disorientation that not only replicates what Elwood, Turner, and everyone locked in with them, were forced to endure, but might also describe what the ABC television crew in the docudrama September 5 experienced, as they find their coverage of the 1972 Munich Olympics quickly turning from “sports” to the kind of terror-infused “breaking news” that’s been with the world ever since. Another awards contender, it shares a Globes picture nod with Nickel Boys in the drama category, and an editing nomination for Hansjörg Weißbrich at the Indie Spirits (along with an editing win from the LA Critics Association, split with – yes, Nickel Boys again, and the work of editor Nicholas Monsour).

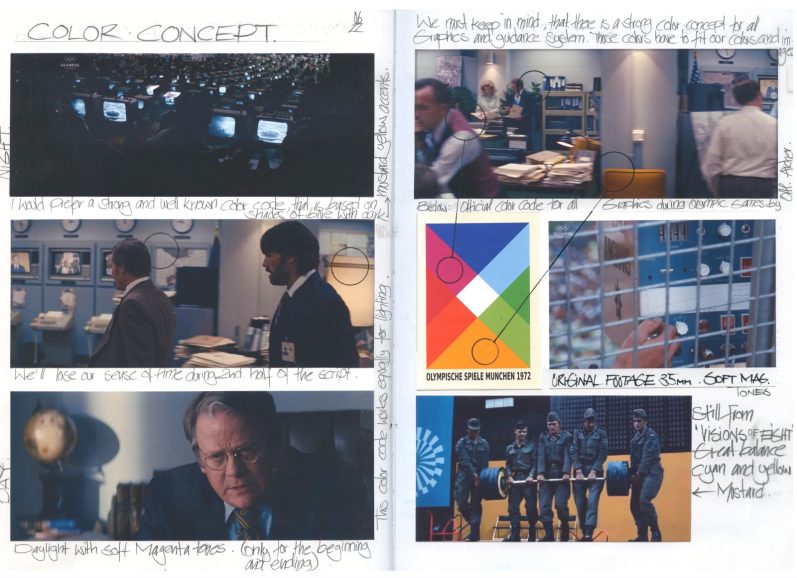

The film moves at a quasi-real time pace, and takes in not only the drama in the control room, as the crew realizes they are the only ones on the spot covering what is no longer an athletic competition, but instead the terrorist kidnapping – and eventual murder of – most of the Israeli Olympic team. This in an era of heavy TV cameras moved on pedestals, limited, shared satellite time, and the word “terrorist” itself barely in the popular lexicon. Combining elements from the behind-the-scenes story, and the broadcast one that the public saw, the riveting film continues to steadily attract award season notice.

As we tend to expand our range of conversations and collaborative insight during the months we’re in Award’oeuvre mode, we had a chat with September 5’s production designer Julian R. Wagner, who had previously worked with director/co-writer Tim Fehlbaum, and cinematographer Markus Förderer ASC. Wagner specifically mentioned Fehlbaum’s earlier far-future apocalypse-themed The Colony saying he and Forderer were subsequently “able to build on our shared experience… I think we share a very similar sense of visual language and lighting aesthetics [and] I admire how Markus lights every set in a way that feels both cinematic and emotional, all with minimal technical effort. This approach aligns perfectly with my preference for integrating light directly into the set design.”

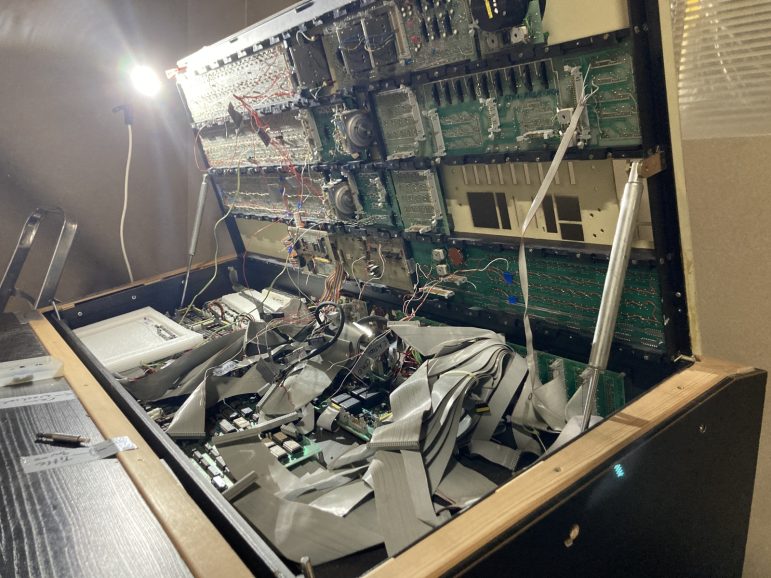

This became even more important with a set replicating a working TV studio and more critically, the control rooms behind it, each with their own diegetic lights, screens, and monitors.

“We decided to build the entire studio set without floating walls,” Wagner says. “There were no moving elements to disrupt the workflow. The size of the set was critical — it had to be scaled perfectly to allow the cast and crew to move freely while still conveying a sense of confinement in every frame. To achieve this, we used subtle tricks like false perspectives and varying ceiling heights. We hung lamps and curtains to visually divide the high overhead space. The room was packed with details so the eye rarely found empty areas, yet it had to feel modern and technical, not cluttered.”

However, ‘unlike the original studio blueprint, we created sightlines into illuminated rooms beyond the control room to break up the closed space and add depth. For the overhead lighting above the control panel, we drew from the original design, but modified the lamps to fit Markus’ preferred light sources. We also left out a large portion of the ceiling so he could light the set from above. This was an exception, as all the other rooms required ceilings to work for various camera angles and to further narrow the focus on the characters. The yellow curtains hanging from above were not only historically accurate (to protect the video wall from spotlights), but also helped block the missing section of the ceiling. The video wall became a key feature in the room, serving as both a prominent visual element and an essential light source […] I can anticipate,” he adds, “ Tim and Markus’ unique way of working on set in advance, and it almost naturally becomes part of my design process. It’s the best shorthand there is.”

Shorthand is also something that the aforementioned Lajos Koltai ASC HSC, Oscar-nominated for his cinematography in 2001’s Malèna (and a regular collaborator with lauded Hungarian director István Szabó ) talks about now that he’s been in the director’s chair a while himself. His current historical drama Semmelweis, chronicles doctor Ignác Semmelweis’s struggles to reign in an epidemic surging through a maternity ward in 1847 Vienna, fighting for simple measures like better sanitation – this a decade or two before Louis Pasteur connected things like “bacteria” to other things like “infections.”

The film was Hungary’s Oscar selection – and already a best picture award winner there – but didn’t make the Academy’s shortlists (which shows again how much engaging work is necessarily given short shrift, with so few available slots relative to the number of films and shows, despite the way “award season” itself seems to always be expanding).

On working with his cinematographer, András Nagy, HSC, Koltai notes they’d already collaborated before, with Szabó, where Nagy both operated “and was my digital camera specialist.”

Their own shorthand came in developing “a technique that made the camera feel like it was breathing with the characters. During an emotionally charged scene, we used a flexible rigging system that allowed us to move seamlessly through the space, capturing the raw intensity of an actor’s performance without disrupting their emotional state. There is one scene, a birth sequence, where the actress had to embody a raw, almost primal state of fear and exhaustion. She gave everything to the performance, and […] our camera system allowed us to adapt instantly to her energy, capturing every flicker of emotion without breaking the flow.”

The actress would later confess to Koltai that she spent a week in bed after the scene!

“As a cinematographer, I used to hear István ask, ‘did you see the angels fly?’ during a take, and I knew exactly what he meant. It’s that intangible moment when everything aligns, the light, the camera, the actor’s soul, and you feel something transcendent happening in front of you.

“My transition to directing hasn’t been about leaving cinematography behind, it’s been about stepping slightly to the side of the camera while still carrying my lens with me”.

Other transitions this season also resulted in notable films – one on the documentary, the other on the narrative side – that may also get lost in the year-end shuffle. One is from actor Jack Huston. Known for his work in Boardwalk Empire and other shows – he’s even played Judah Ben-Hur and Jack Kerouac – here he takes to the director’s chair, in the manner of his grandfather, John Huston, to helm the indie boxing drama The Day of the Fight.

It was even one of his granddad’s lesser known films, 1972’s Fat City – with Stacy Keach as a down-on-his-luck boxer in Stockton, California (located in the state’s agricultural Central Valley) that he watched as part of his prep with actor Michael Pitt, another Boardwalk Empire alum, who stars as the fighter whose existential “day” – and all the ghosts and bad decisions still haunting him – reaches a kind of apotheosis in that night’s potentially redemptive, last-chance fight.

It’s set only some ten or fifteen years after Fat City, and if it seems familiar, why, we discussed the film with cinematographer Peter Simonite ASC CSC, in our last column of last year. Catching up with Huston later, he said that “finding Peter” to shoot the B&W film “was one of the great wins for us.There was a certain [Terrence] Malick-esque sense to what we were doing.”

Other 70s-era sensibilities pervaded our interview when Huston saw a framed Chinatown poster behind me – a film memorably co-starring his grandfather as as the wealthy, water-stealing Noah Cross – and cited that film’s producer, saying “Bob Evans worked with great people – great actors, writers, directors […] I had a wonderful group surrounding me [too]. The entire crew from top to bottom, [was] at the absolute pinnacle of their work,” as he goes from department to department, citing names for costume, locations, production design, camera operators and more. “Every person added to this collaborative aspect. Every now and again that’s where the magic happens.”

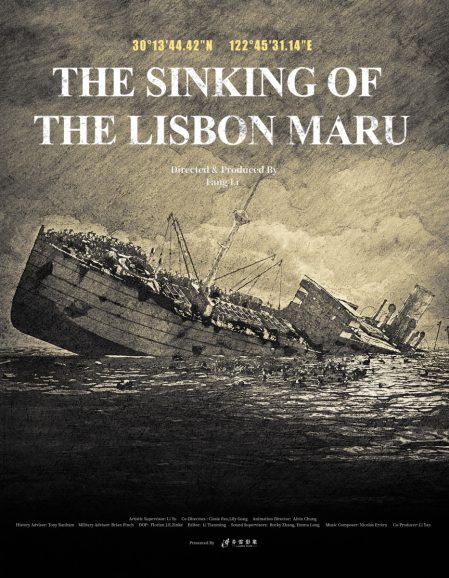

On the non-fiction side, producer Fang Li, known for international fare like Lost in Beijing, suddenly found himself becoming a director, too, for his first documentary, The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru, mostly because he calls the film a “volunteer” effort, “since I know I can never make money.”

The film recreates the story of the ship, laden with mostly British POWs in World War II, which sank under friendly fire as it took prisoners from Hong Kong to Japan. Some managed to escape into the water, where the Japanese Army fired upon them. Some members of the Imperial Navy attempted to hang on to the last vestiges of wartime “rules” by trying to rescue them, though more help came from Chinese fishermen from a nearby island, who fished them out of the ocean, and brought them back to their village. From there, a couple POWs ultimately escaped, though others wound up in land-based prisons after all.

Li, like much of his audience (including this columnist) was startled to learn the story and wondered why he hadn’t heard it before. Though as a geophysicist (it’s good to have a fallback, when in showbiz) his first task became to finally locate the remains of the ship itself.

From there, he wanted to track down survivors, or likelier at this juncture, surviving relatives of survivors (including in the village, and of the Japanese crew), so – as with many docs – part of the film is a detective story.

In a reception after a showing here, Li told us that once the project shifted from being a television documentary to a theatrical one (where it’s already become a hit in China), he waited for his frequent cinematographic collaborator Florian Zinke to become available, saying the change meant that in interviews and other sequences – such as an at-sea commemoration for lost POWs whose families had never been able to grieve them before – the composition, “camera moves,” and other visuals changed, going from something formerly “static” to becoming more fully “alive”.

Of the 800-plus prisoners, each one represented “a life,” Li said, and in tracking down memories, passed-down stories, and the very small handful of remaining survivors, he said “every day we were in tears,” working the film.

Which speaks to the power of the medium, and what keeps drawing people to it. As for what lays ahead in the post-strike, AI-riddled and increasingly culturally-riven future of said medium, at WiM’s Toast, when honorees were asked both about advice for people coming up in the biz, and what may lay ahead, it was Oppewall who said someone might want to consider another line of work “if you are not a flexible personality.” Not only does one have to endure, she said, but also “set an example of how to endure,” adding that in work, and life, and wherever they overlap, one shouldn’t “be afraid of the detour.”

So may your detours in this Brave New Year be fruitful ones, and we’ll see you a wee bit further along in the journey.

@TricksterInk / acrossthepondBC@gmail.com