Our stateside columnist Mark London Williams speaks to Oren Soffer, one of the dynamic DP duo behind AI epic The Creator, and makes for the Emerging Cinematographers Awards, where industry greats rub shoulders with up-and-coming stars.

“Our lighting approach was in tune with our desire to create a free, open-to-spontaneity guerrilla film.” In our very busy column this month, one of our stops was ICG 600’s recent Emerging Cinematographers Awards, honouring the work of upcoming DPs – many recent graduates – and their short films, all over a big weekend filled with accolades, networking, and a screening of all their shorts. And you would think that quote about a guerrilla aesthetic – given all the budget-stretching that usually has to go into such work – would come from one of them.

Instead, it’s from one of the two credited cinematographers on one of the biggest studio releases of the early autumn, Oren Soffer, who, along with Greig Fraser ASC ACS, helped bring director Gareth Edwards’ The Creator to the big screen.

Drawing from sources and inspirations as disparate as Apocalypse Now and Blade Runner, Soffer describes the film as a “love letter to 1970s and 1980s science fiction”, as the, well, creators of this story strove to “evoke [that same] aesthetic feel”. Though he also allows that “to me, the biggest visual influence is actually Alien”, in terms of colour palette and lighting.

The story, however, is very much Earth-based (well, with an orbital weapons platform in the mix), as John David Washington plays Joshua, an undercover operative in a near future seeking to find “the creator” of the sentient – and humanoid – AIs, who have retreated to Asia during a final war with humanity.

Though, as with zombie films too, the question lingers as to which side is actually more dangerous. Or in this case, more humane, which Joshua steadily grows to realise.

Fraser, who had collaborated with Edwards on one of this century’s best Star Wars films, Rogue One, and who is co-producer here, had been developing the project with the director, and his co-writer Chris Weitz, since then. “As it started to materialise,” Soffer says, “they got more specific about the look.”

And there also became more specific reasons for the delays and scheduling changes, namely a certain global pandemic that shut everything down for a stretch. Emerging from that, Fraser was newly busy with not only the first season of The Mandalorian, and its groundbreaking LED volumes, but also the crime fighting adventures of a bat-smitten billionaire, along with a spicy desert planet-set, giant worm-infested science fiction saga.

Soffer, meanwhile, had gotten “very lucky meeting [Fraser, who] took an interest in my work,” which included a lot of well-received shorts, along with features like the darkly Alice-in-Wonderland themed Fixation.

After Fraser “thought of me for this project”, Soffer then “hopped on a Zoom”, and that, he says, was pretty much it. He describes Fraser as “very generous with his mentorship” and also fairly creatively elastic with his time, as both the director and the two DPs “collaborated quite closely. Greig was remote during the shoot,” checking in from both London and Los Angeles, “watching the dailies” while working on his other marquee projects.

The three of them were later reunited at Pinewood during the production process, by which time, use of the camera gear that Fraser had settled on earlier with Edwards was well under way, namely, perhaps surprisingly, a Sony FX3, on its own gimbal rig, with an Atlas Mercury Series 42mm anamorphic lens.

Soffer says Edwards – who also likes to do his own camera operating – had an inadvertent hand in the lens’ development, when visiting the Atlas booth at a previous Cine Gear, looking at their then-current glass, and remarking, “these look great – but can they be smaller?”

Their current set-up allowed them to shoot in 1200 ISO, and use lower powered LED lights, along with “a lightweight dolly and scissor crane. You can get great crane shots!,” and for even higher altitudes, they were able to use a lot of small drones as well.

It was part of a cinematic philosophy that allowed that “sometimes there are other tools for the job,” tools that some people, he says “might consider more ‘prosumer’”.

Prosumer panache

And as it turned out, “prosumer” was one of the watchwords of our big busy weekend. That included a brief chat, returning to the ASC Clubhouse the day after the Emerging Cinematographers’ luncheon there, with Fujifilm’s product planning manager Makoto Oishi. He was there to talk about the launch of their updated GFX camera line, in this case, with the new 100 II, which has a redesigned medium format sensor that Oishi says can handle anamorphic, 35mm, and which “should support all formats”.

The camera clocks in at a four-figure price point, which Oishi calls “quite important” in terms of its intended, and fairly broad, base of users, but also stresses the camera is still the “flagship” for the line, citing the last few years of investment in R&D for the new release.

The event also included a lot of glass being demo’d along with the camera, including lenses not only from Fujifilm, but vendors like the aforementioned Atlas Lens and Hawk.

The idea for the new GFX with its “cinematic function” came, Oishi says, from a philosophy of designing “for what’s next” which seemed to be one shared by Cooke Optics, which had their own event a few nights later at their showroom and offices in Burbank, which have been opened since last year.

Located in an industrial area next to the Burbank airport, Cooke’s American beachhead finds itself with a movie gear-rich neighbourhood that includes Tiffen, Matthews Studio Equipment, and just a couple blocks away, ARRI.

On this particular evening, technical sales manager Chris D’Anna was overseeing a modest, hands-on demo of the company’s new SP3, a new prime lens based on their storied Speed Panchros. The SP3s were hooked to a couple of Sony and RED cameras for the evening, with D’Anna describing these as the “lightest full frame lenses from Cooke”, which also makes them more compatible for drone work, as well.

The price point also hits that “prosumer” range, with a four-figure tab for a single lens, or just north of $20k for a full five glass set. They also come with E and RF mounts, along with L & M versions for Leicas, with “a lot of shims” to enhance the range of their compatibility. D’Anna says other mounts are being tested to make such compatibility even easier, and an instructional video from Cooke is forthcoming.

Learning from the best

The “prosumer” theme was also echoed throughout the Emerging Cinematographers weekend, perhaps not quite as much as the tools used (there were a lot of ARRI iterations, REDs, etc. in the winning films, which you can read about here), but in the bountiful swag given to the finalists after the ASC luncheon, which included things like GoPro cameras, and ‘welcome-any-time’ certificates from Chapman/Leonard and Abel Cine, LED kits from Rosco, another one for colour correction time, along with many other items, scaling all the way up to $90,000 worth of gear from Panavision, another of the event’s cosponsors.

A couple of the DPs involved were already members of 600, and working as assistants, compiling a lot of shorts, and generally already in, or headed to careers in cinematography. Steven Poster ASC oversees the ECA, and of course, along with the many jaunty hats he wears, is also a fellow columnist right here for British Cinematographer. He said the programme honours “our newest talent” and, at the ASC Clubhouse, does so at a venue that provides “a sense of history that doesn’t exist anywhere else in our industry”.

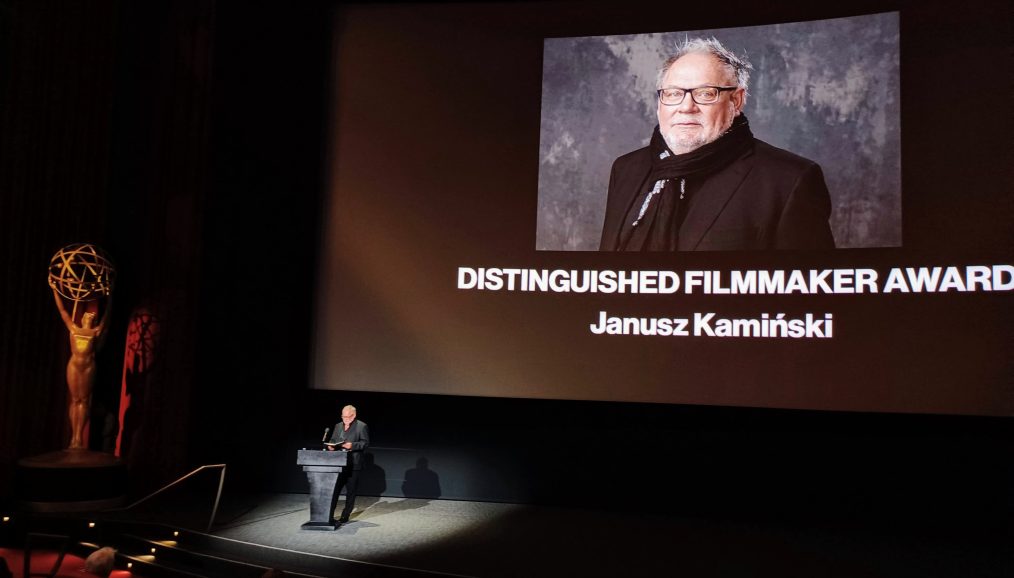

The event was also attended by ICG president Baird Steptoe, and ASC president Shelly Johnson, there not only to honour the emergent lensers, but also the event’s two other honourees, former ASC president Stephen Lighthill, receiving the ASC Mentor Award, and Oscar-winner Janusz Kamiński getting the distinguished filmmaker award.

Lighthill – who Poster introduced as having “developed the best cinematography school in the world” (at AFI) – spoke at the Friday luncheon, whereas Kamiński received his award at the Sunday evening screening of the films themselves, held at the Television Academy’s theatre in North Hollywood.

The ever-thoughtful, modest Lighthill mentioned that “we’re all put on this planet to help each other”, an admonition that in a time of bitter showdowns, increasingly irreconcilable divisions, and now a further eruption of war and bloodshed in the Middle East – the latter just since this column was started – now feels both more necessary, and more quixotic, than when he made it.

He also remarked that “cinematographers are natural educators,” and part of their on-set objective was to get as much of the crew unified as possible.

In his brief remarks on Sunday, when receiving his own award, Kamiński, admitting to being nervous, also gave a shout out to Lighthill for the AFI programme, and also joked about growing up, in Poland, under the wrong kind of union – as a satellite of the former Soviet Union – and being glad for the many years he’s been a proud 600 member.

On which note, for readers looking for strike updates, of course Hollywood’s own labour impasse has been “half settled”, with the accord between writers and producers. But still, no one can return to a live, active set without actors, so we await the AMPTP agreement with SAG-AFTRA. That would seem likely to have happened before we see you again here in November. So we will hold out for that rare good news against the other tidings that flood in from ‘round the world.

Which brings up something else Soffer said about The Creator. Once Edwards has finished editing a film, then “Gareth is going to go in with ILM and the production designer [James Clyne],” and working with the VFX supervisors, finish designing the science fiction and FX elements on top of the otherwise “finished” film. “Certain shapes [of devices, vehicles, structures, etc.] – those things were designed to frames we shot on location,” with the aesthetic “driven by what we shot on location, and not the opposite”, nor with an over-reliance on green screens.

“We intentionally took the opposite approach,” Soffer says, “in order to cut costs and [create] a reality that feels more lived in.”

Well, there’s no question that our reality increasingly feels more and more “lived in” by all of us, these days, and increasingly shared, as well.

We’ll see you in a month after we go through a few more weeks of it together.