TIME FOR REFLECTION

Challenged with crafting the dystopian world for Silo, DP Mark Patten BSC made the most of the Lightbridge CRLS system to shape the Apple TV+ series’ dark visual language.

When composing the short story Wool, author Hugh Howey envisioned a future where humans live in a 350-year-old subterranean city that is 140 storeys below a deadly toxic surface; the dystopian concept was expanded into four sequel novellas and adapted into an Apple TV+ series called Silo by creator Graham Yost. Yost partnered with directors Morten Tyldum, David Semel and Adam Bernstein; actors Rebecca Ferguson, Tim Robbins, Rashida Jones, and David Oyelowo; and cinematographers Mark Patten BSC, David Luther, and Laurie Rose BSC.

Brought in to lead the DP team, Patten discovered that despite framing for 2:1 rather than 2.39:1, filmmaker Morten Tyldum wanted to go anamorphic for the pilot episode.

“We used a new set of lenses developed by Caldwell based on Panavision anamorphics called Chameleons,” states Patten. “We had 32mm, 40mm, 50mm, 60mm [favourite], 75mm, 100mm and 150mm which leant themselves to a narrow set of criteria of which to cover each scene; it became our visual language, a limitation that brought structure to the idea that we are always to be with our character.

“We weren’t shooting on a 35mm sensor but on the ARRI Alexa Mini LF and that, combined with the 2:1 ratio, resolved a unique bokeh that, with the qualities of an anamorphic lens, created its own cocktail. You had an interesting depth of field created by the choice of glass and then the characters were separated from the background. The director, Morten Tyldum, was adamant that the silo be its own character.”

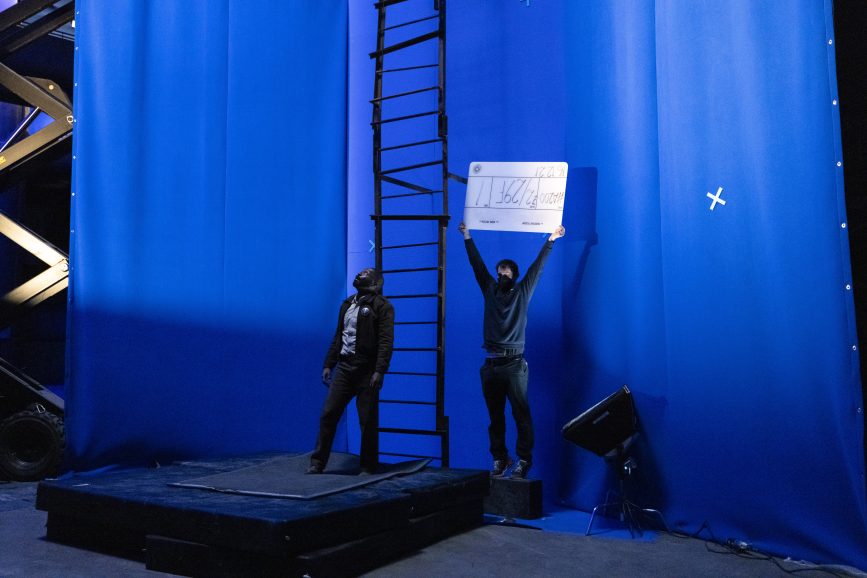

A major challenge was conveying a proper sense of scale as the environments and sets should never feel contained. “However, with the use of the previs by [visual effects supervisor] Daniel Rauchwerger, we could look up or down the ‘Y’ axis and render a real-time image of the internal dimensions of the silo,” notes Patten. “Whenever we travelled vertically through 140 floors, we only had one floor, so the art department would have to go in there change it all up or paint it a different colour. We had a generic floor and above and below was bluescreen. If you would telescope out, they could change it depending on where you were in the silo. It was a scheduling nightmare.” A bluescreen floor was created so that visual effects could augment the bigger shots.

“We shot our pilot as one block and then the other blocks started shooting,” explains Patten, who relied mainly on two cameras and a third for the big sets, while the other units adopted the same footprint. “They would shoot behind us and shoot out the sets. But there were certain sets that were common to all the blocks.”

A lookbook was created by DPs Patten, Luther, and Rose. “For DPs who have started to get involved with huge streamers, collaboration is key. If we all go to the one set – say, the ‘engine room’ – you can’t light it differently,” says Patten. “Granted, each director blocks scenes in their own way but as long as the overall look and aesthetic is beholden by a loose set of rules, you’re going to get a show that has a strong backbone.”

Repetition was unavoidable for the 10 episodes. “By the end of the year there is not an angle that has not been shot; that’s the nature of big TV. An interesting conundrum was how to move the camera up the central staircase in a fluid narrative. Do you technically do it with a wire cam or crane? Everybody had their own stab at it. One block had to race 40 floors up and we only had two and half spirals onset. You’re constantly having to use camera trickery to get that scale. It was an interesting puzzle to work out.”

10 weeks were spent in prep while principal photography lasted 180 days in a former KFC cold storage unit, because there was no stage space in the UK. “I felt like a chicken wing after eight months!” laughs Patten. “Alongside gaffer Brandon Evans the team had to pull those cold storages apart and integrate all the rigging to retrofit the space into a working film stage. We hung lighting rigs before the sets were built because, otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to start the build to get in.”

LED lights were built into every set under the supervision of Patten, gaffer Evans, production designer Gavin Bocquet, and supervising art director Phil Harvey, and connected to a wireless control system. “That allowed us to have total control over all stages. Lightbulbs are a sort after commodity in the world of the silo, so we used LED to control the overall tone. It’s standard practice on these large sets to put big 40×40 softboxes plumbed into the rigging that contain ARRI SkyPanels.”

Precision Reflectors from Lightbridge became indispensable tools. “There is no daylight you could push through the windows, so you had to shape soft reflective light,” remarks Patten. “The CRLS system has five different sets of reflectors so if you want to intensify the light you can throw it into a harder reflector, but it’s still reflected. Using that criteria, I threw reflective light around the rooms a bit more and enjoyed playing with that aesthetic in the final block of shooting. Sometimes we had three or four outside of the window and then we would play that reflective light around each set, the ability to control reflective light and create an environment to allow the actors to inhabit the sets was liberating. You would have a soft 4 1X1 reflector and then combine a hard 2 25×25 to direct the light in the middle of a singular light source, so you’re almost getting two qualities of light from the system. It’s very cool! Also, by the end of the year I was getting used to going through the same lighting scenarios, when this came into my wheelhouse it was like, ‘Wow! I can actually start to have a bit of fun again.’ I wish I had known about the CRLS system earlier on in the prep because I would have had it on the floor for the whole project.”

Texturing was an important aspect of the set design. “The textures in all of the sets were incredible,” says Patten. “Nothing was flat. The cafeterias existed on every 10th floor; these communal rooms are where the populus can go to unwind from their drudgery in this dystopian hellhole that they find themselves in.” The video feed of the outside world that surrounds the set was achieved through virtual production.

Imagine a giant TV screen that runs around the whole of your periphery. Initially you would wonder if that is a view to the outside world but slowly as the story evolves you realise that those screens are a piped picture from above the surface which is a dead world. There has been some kind of environmental catastrophe and that’s why they’ve taken to the silo.” The only exterior photography captured was on the first day of shooting for the live feed from the exterior camera.

“We had to decide whether to make that window to the world a bluescreen and add that later in post, but I wanted the reactive light coming off of the window to feed back into the room. By week five, the visual effects team had worked on the asset, so we started working in the cafeteria sections with a virtual wall that was pumping that imagery into the set. The screen was a good 100 feet across. That environment changed from night to day to dust storms so you could feel the change of what that virtual wall did inside the actual set itself.”

One show LUT was developed for the ARRIRAW footage. “That was made available for all the DPs so there was a parity to work to,” says Patten.

“What is happening in the shadows in the silo is quite interesting. You’re always fighting with a bit of negative, so you don’t look too deeply into those areas. There wasn’t too much contrast. I didn’t want it to be black-black but be able to see into those parts of the set because the textures are so interesting and I’m hoping that the audience will notice them. I’ve worked with my colourist for a long time, Luis Reggiardo, and settled on a tweaked Technicolor base LUT which has filmic properties. With these LUTs you don’t know where to stop! It doesn’t need to be too complex, otherwise when you pull it back to the DI and final colour sometimes it can really change the look. It is important to establish a strong visual statement at the beginning so that everyone down that pipeline becomes used to that look and it is embedded in their minds even a year later. With Greg Fisher at the helm for final colour, the show’s look was nuanced and polished but never deviated from the initial idea, which is great.”

Each zone has a different colour palette that is muted and diffused. “Hopefully, when the viewer looks at each episode the colour helps them decide where they are in this shaft,” says Patten. “The mechanical level became quite desaturated with only one specific colour which was amplified in the final grade. With the diffused light we were trying to keep that aesthetic in play. Each cell had an art directed colour; the photography had to honour that formula. We had to figure out how to pull that out with the lighting. You can do a bit in the DI but as I’ve got more mature with my lighting, I like to bake it in or be braver. Simplify it. It’s good to be strong and bold with your choices.”

Visual effects were extensive. “Once you go off the main shaft then you’re into sets that don’t have bluescreen,” says Patten. “I wanted the whole warehouse to be blue because whatever angle you look at was a visual effects shot. You have to worry about the blue spill and there were a couple of greenscreens. You get used to it and backlight it out.”

Key collaborators not yet mentioned include production designer set dresser Amanda Bernstein, A-camera operator James Layton, B-camera operator Justin Hawkins, and key grip Tony Fabien, while the camera and lenses were supplied by ARRI Rental UK and lights by Panalux UK.

“The concept art was critical because it’s an environment like no other,” states Patten. “If that’s the imagination then you need to know as early as possible how you’re going to formulate to light this vast structure.” The bigger sequences were storyboarded. “It is essential that cinematographers present themselves as co-collaborators and listen to the directors because you’re ultimately serving their story. Once you understand that relationship it makes you aware of each other through the working day; that’s part and parcel of these big shows, how do you fit in with everybody around you because it’s all to do with collaboration.”

Keeping continuity in the main silo itself was difficult to achieve. “This giant generator gets powered down and all of the lights go out in the silo,” says Patten. “Then there is the jeopardy of whether they can get that system up and running again. With the CRLS system the reflectors guaranteed exposure in the blackness of the silo!”

–

This article was sponsored by Lightbridge. For further information on Lightbridge, CRLS – PRECISION REFLECTORS, please visit here.