Article written by Pete Allibone

–

A lot of people love a good gangster flick and there’s no shortage of real-life candidates to focus on. It’s a genre unto itself, but it’s rare that gangsters are closely related and even rarer that they are twins, like Ronnie and Reggie.

The Krays reign over London’s East End in the late 60s has been the subject of countless books, documentaries and feature films that pour over the intimate details of their shady lives. All this made Code of Silence a daunting prospect, even before factoring in the damp, dark and dreary warehouse location, in the middle of the winter lockdown, on a limited budget.

Prep Period

Picture Perfect Productions opted to produce the script written by Luke Bailey with Ben Mole directing. Ben and I are long time collaborators and he brought me on board. Much of our prep time however, was spent figuring out how we were going to shoot this notorious duo with just one actor. We were lucky enough to have the very talented Ronan Summers to play both Ronnie and Reggie Kray – in much the same vein as Tom Hardy in the 2015 film Legend.

However, this time, rather than using camera trickery and a very close lookalike to play all but the close ups, the hope was that “deep fake” technology would allow us to simply paint Ronan’s face onto another actor, thereby freeing up the camera to shoot like a regular film. Similar technology has been used on recent Hollywood epics such as Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, which in 2017 recreated and reanimated Leia, after the sad passing of Carrie Fisher. Thanks to the relentless pace of VFX development, five years on, this revolutionary and mind-blowing technology is now within reach for productions with shallower pockets. We worked with James Dean at Liminal Studios to test the process, which meant ‘teaching’ an AI component of a programme the precise shape and degree of movement of a subject’s face, from any conceivable angle and with a variety of expressions. Once the computer knows the subject’s face well enough (which can take several days of processing), it can simply be ‘pinned’ over the top of another actor’s face and tracked as a moving target. All this, without the need for a locked-off frame, or even a particularly steady shot for that matter.

Sadly, despite a variety of YouTube videos that demonstrate this as a simple process, in reality, the software can still be tripped up by low-lighting, funny fringes and creeping collars! We desperately wanted to make it work, but with two weeks to go, we had to fall back to plan B – a series of precisely framed, lock-off shots when we needed both Ronnie and Reggie in the same frame, hidden wipes between separate singles and a stand-in for a foreground body bite when we were in a position to shoot regular over-shoulder shots.

This also meant that rather than a lot of the heavy lifting being done in post, we had to factor in extra time to shoot the A and B parts of various split screen shots and to flip Ronan between his two characters. It also reinstated the classic headache of background and lighting continuity for the lock-off shots, (so that both halves of any frame splices match perfectly). Unsurprisingly this proved fairly stressful with the limited daylight available in February/March and at a location with vast windows.

Our shoot schedule was just 14 days, meaning an average of 7-8 pages of dialogue per day – a challenge in itself – but on top of that some scenes involved Ronan switching between roles. Our extremely talented hair and make-up artist Broadie Mayhew worked wonders to physically change the shape of Ronan’s face when he was playing Ronnie. Her dedication and efficiency made it possible for us to shoot the fight scene between Ronnie, Reggie and Nipper at lightning speed, whilst never seeing more than 2.5 of the characters at a time!

Since some shots required the camera to be locked off whilst Reggie became Ronnie and visa versa, we couldn’t afford not to be shooting during that turnaround time. So, a second camera body in addition to our Sony Venice A-Cam was essential enabling us to continue shooting whilst costume and make-up departments worked their magic.

The second camera was a Z-Cam E2-F6, which is a fantastic little bit of kit that I never fail to be impressed by. It’s essentially a 4” cube with multiple lens mount options, duel native ISO, a full-frame 6K sensor and fully controllable and viewable over Wi-Fi for when it inevitably gets mounted in awkward positions. I have used it on previous projects and it grades up alongside Venice footage extremely well. Not only that, but being so small and lightweight, it also happens to make a perfect Gimbal-Camera.

Movement

Our set was an old warehouse complex in south Wales, which offered endless eerie corridors and vast dramatic spaces. Luke and Ben restaged a lot of the dialogue to work whilst walking, or on the move in some way, so we could show off the wonderfully cinematic nature of the industrial location. This meant the camera also needed to be free to move as much as possible too. And at times, over far longer distances than track would ever allow.

A Steadicam wasn’t an option for us, so we made use of a Ronin2 hung from an EasyRig. Mounted to this was our Z-Cam F6.

However, for some of the longer corridor shots I spent some of my prep time adapting an old wheelchair I bought from eBay so we could mount the Ronin to that. Not only would it promise to be a little smoother, but it could be mounted with the lens anything from 6” from the ground up to 6’ high – positions that would be very hard to manually hold the camera in for any length of time. We also had the benefit of a fully remote controllable head, courtesy of the DJI remote.

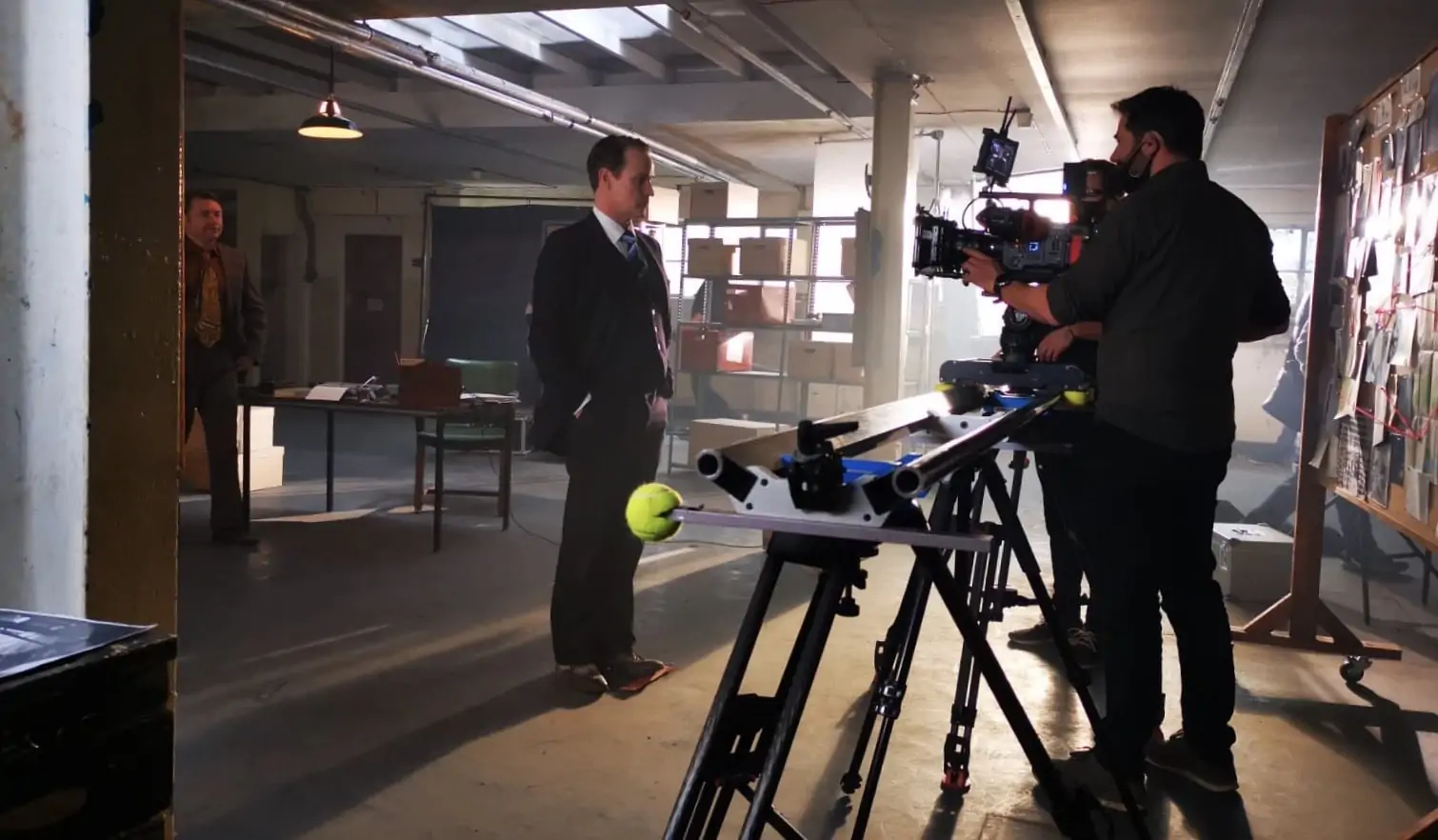

The only other grip gear we had was a Solid Systems Slider, with 3’, 4’ & 5’ rails.

I highly rate this slider for its ability to get the camera lower to the ground than any other system I can find, but simultaneously it’s incredibly heavy-duty and able to be mounted very quickly and sturdily, at any height a tripod can get it to and even inverted for more elaborate shots if required.

Glass

We made use of my own Zeiss Supreme Prime lens set for this film, which I love more and more every time I strap them on. They truly do exactly what they say on the tin: “a gentle sharpness, crisp yet flattering to skin tones and with an incredibly smooth focal fall-off and elegant bokeh”.

The consistency of stop and contrast throughout the range is stunning and I was supremely grateful for their incredible T1.5 stop in a lot of tricky lighting situations. Although I now have the 18mm too, when we shot Code of Silence the set began at 21mm and included the 25, 29, 35, 50, 65, 85 and 135mm. So, I was confident we had a very healthy range of focal lengths for the extremely tight spaces we were going to be in, as well as the vast warehouses. These incredibly fast lenses also gave us a fighting chance given we were not blessed with time to pre-light, and had a distinct limit on the amount of power available to us.

The script included a series of key flashback sequences, which were used as an interesting narrative device for Nipper (our hero detective played by Stephen Moyer) to walk through as he re-imagined the crime scenes.

I felt this needed to have a distinctly different look to the rest of the film, dream-like, and slightly fantastical, to distinguish it from reality. This automatically points toward anamorphic glass. Even though our aspect ratio was 2:1 not 2.39:1, (so we would inevitably lose some of the resolution at the sides) there is some precedent for using anamorphic lenses in this way. Doctor Who, BroadChurch Series 3, Fleabag and countless Netflix shows have used anamorphic glass for its softness, foreground separation and lush flares. In this case it meant the effect I hoped for was still there, but it was subtle enough not to be jarring when cutting back to spherical lenses.

I used a set of Vazen anamorphic lenses for these scenes, which are both full-frame and surprisingly fast at T2.0. The set comprises of only 3 lenses, but by switching between Super35 mode and Full frame, we essentially had 6 different fields of view.

Light

Lighting the spaces we found whilst scouting was a intimidating prospect with our lighting package. The site was an enormous, semi-abandoned industrial site, which offered huge, cinematic interior spaces, with heavy plant machinery still in place for us to work around.

Some rooms had sky-lights and some had banks of windows on one, two or three sides. Some of this we could control with judicious use of corex, blackout drape and sheets of plastic. Some we could not as we were simply too high up and had no cranes or cherry pickers.

At times we had to simply embrace these spaces for what they were and allow the windows to blow out if the weather wasn’t playing ball or block the actors into the zones that we could control. The latitude of these cameras was pushed to their limits on more than one occasion. As was the strength of several crew members who volunteered to hold down a tent structure placed over the windows of our Blind Beggar pub location, whilst we filmed day for night interiors and the weather turned from sunshine to howling gales, to sleet and snow then lashing rain over the course of just one scene! Forever grateful to Matt Welfare and Al Mole for their fortitude and excellent blood circulation!

I underestimated the early spring Welsh weather somewhat. I had hoped for flat but consistent light for a few key situations where we were shooting outside but we had to accept whatever was thrown at us. In hindsight it was a foolish hope located as we were on the southern tip of the Brecon Beacons, but I learned to fight the battles I could win and simply lean into the things I wasn’t able to control.

Many years of documentary shooting have taught me to make the best of what you can in any given environment, play to the strengths of the set you have in front of you and time your wide shots extremely carefully in inclement weather.

Consistency was the hardest part of lighting for this movie. Due to our already compressed schedule, as well as all the usual challenges of melding actor availability, make-up and costume turnaround times or location availability, we often had to shoot dramatically out of sequence. The scene set in the Krays’ RR club for instance was actually filmed in 3 different locations, weeks apart from each other and in 3 different rooms that bore no resemblance to each other. Thankfully, no one else seems to pick up on it, which is a relief!

A large portion of the film takes place in the main office where we would often have to shoot a daytime interior followed by a night interior and then back to daytime, but now from an earlier part of the film. The lighting needed to evolve across the story to reflect what was happening, we had to manage the level of contrast in a space the size of two tennis courts, with limited power. We only had a couple of small HMIs powered from domestic mains, a few tungsten fixtures in soft boxes and small LED kits like Astera tubes small battery powered panel lights.

There were scenes in this main location with up to six-way conversations happening, as multiple characters moved around the room simultaneously.

This meant taking advantage of the various holes in the dilapidated ceiling to make our own skylights and blocking the actors into the areas we could control. We were lucky to be blessed with an extremely versatile and understanding cast!

After 14 frantic days of filming, we all felt we managed to pull off a film we could be proud of. So much credit must go to the actors delivering incredible performances at such a furious pace. They’re all absolute gangsters in my mind.

Code of Silence is released on 27th December.

Article written by Pete Allibone