Most Effective

ClapperBoard / Brian Johnson

Most Effective

ClapperBoard / Brian Johnson

BY: David A. Ellis

It’s amazing what you can do when you put your mind to it. Brian Johnson left school at sixteen with just one 0-level but, through some lucky breaks and undoubted skill, rose to become pre-eminent in the field of special effects, winning an Oscar for his fearsome model work on Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), followed by another golden statuette for special visual effects on Star Wars: Episode V - The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Johnson was born on 29th June 1939 in Surrey. Although he occasionally went to the cinema as a child, notions of working with film were far from his mind. His early ambition was to be a pilot. However, a break came when he was offered a job sweeping the floor at Addlestone Studios, a converted church in Surrey, which was home to Anglo Scottish Pictures. Whilst he was there he was shown how to load film and went on documentary shoots, working around the UK. He then left Addlestone and went to work as a camera assistant at Lintas advertising agency in London. Johnson was then called up for national service and spent two years in the RAF, working on landing systems.

Following his demob, he went back to Addlestone to join the team of special effects artist Les Bowie, at Bowie Films, who had a matte painting studio where they did work on Hammer Films productions and movies such as On The Buses. The first film Johnson was involved with was The Day The Earth Caught Fire (1961). He descibes Bowie as “my mentor”. Some sources say that he worked with Bowie on the Hammer movies Taste The Blood of Dracula (1969) and When Dinosaurs Ruled The World (1969). Johnson says those films were without Bowie being directly involved.

One day Johnson recieved a call from director of special effects Derek Meddings, with whom he had worked previously at Anglo Scottish, asking if he would help with the models on a new Gerry Anderson production Supercar, being made at Slough. It was a successful move, and Johnson continued to work with Anderson, firstly as a model builder and flyer, on the popular TV series of Fireball XL5 and Stingray, and then later as second unit director on the groundbreaking Thunderbirds series.

"We discussed how we would do the sequence where the Alien comes out of John Hurt’s body. When I came to do the film we made a false chest rig and pumped pints of what looked like blood through the ripped T-shirt."

- Brian Johnson

With this considerable experience under his belt, Johnson wanted to segue into features and moved to MGM, where he spent three and a quarter years, and prepared miniature spacecraft models for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

“Building of the models was done by Space Models at Feltham, and designs were done by Harry Lange, Tony Masters, Ernie Archer and Alan Thompkins,” he said. Johnson wasn’t credited for his skills and Stanley Kubrick took the effects Oscar. “It should have gone to Doug Trumbull, Wally Veevers, Con Pederson and others,” added Johnson. He then went on to Mosquito Squadron (1970).

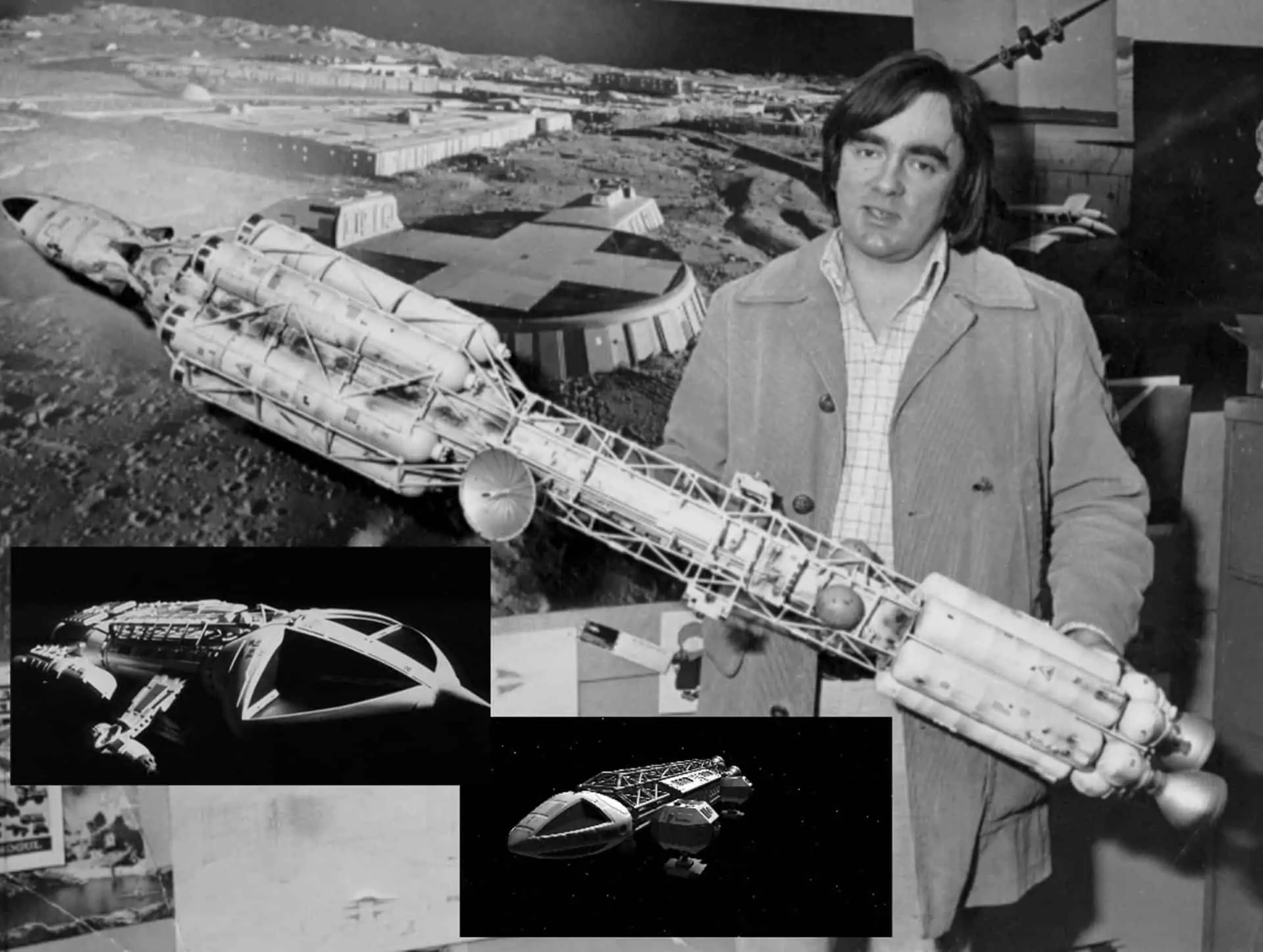

Johnson then returned to work for Anderson to do effects for The Protectors (1971-1973), before working as special effects director on Space: 1999 at Bray Studios, where he designed and built the show's various vehicles, including the iconic Eagle Transporter space shuttle. Rather than relying on the then expensive and time-consuming bluescreen process for Space: 1999, Johnson's team employed a technique that went back to the earliest days of visual effects: spacecraft and planets were filmed against black backgrounds, with the camera being rewound for each successive element. As long as the various elements did not overlap, this produced convincing results. Johnson says that they had to complete six model shots a day, but the results proved to be of the same quality achieved on 2001. Indeed, it was this work that would eventually influence the effects of the Star Wars movies of the 1970s and 1980s, and the effects on Space: 1999 still stand up today.

During this time a young director called George Lucas came down to see the set-up with several others. Johnson said, “I was told that a big space film (Star Wars) was going to be made at Elstree Studios and I was asked if I wanted to work on it. Having already been commissioned for the second series of Space: 1999, I was unable to accept Star Wars. I did the second series of Space: 1999 and then started looking around for other things to do before The Empire Strikes Back. During this period Peter Beale from 20th Century Fox asked me if I would talk to director Walter Hill, to discuss a picture he was going to make called Alien. I went to see Walter and we discussed how we would do the sequence where the Alien comes out of John Hurt’s body. When I came to do the film we made a false chest rig and pumped pints of what looked like blood through the ripped T-shirt.”

Johnson noted: “I expressed my concern to Peter Beale that work on Alien and The Empire Strikes Back might clash. As they were both Fox productions, he said he would sort it out with the powers that be. So the agreement was I would work on Alien first and then go on to The Empire Strikes Back. Walter Hill, for whatever reason, decided to leave the picture and was replaced by Ridley Scott. A lot of the special effects were shot at Bray Studios because there was no room at Shepperton where the live action was being shot. At Bray we had complete control. We could do what we wanted, when we wanted. Alien was still being shot when The Empire Strikes Back was ready to start, so I had to leave it in the hands of my excellent team. They later joined me on The Empire Strikes Back, where I supervised special and visual effects at the now world renowned Industrial Light And Magic. Ridley thought I had walked out on Alien, which I hadn’t.”

It hardly mattered though as Johnson’s special effects work was recognised in the form of the 1980 Best Visual Effects Oscar for Alien (shared with H.R. Giger, Carlo Rambaldi, Nick Allder and Dennis Ayling), followed by the 1981 Special Achievement Academy Award for The Empire Strikes Back (shared with Richard Edlund, Dennis Muren and Bruce Nicholson).

At the request of Lucas and Steven Spielberg, Johnson went on to work on Dragonslayer (1981) and was nominated for another Academy Award, but was pipped at the post at the 1982 Oscars by Raiders Of The Lost Ark. Although this proved to be his final Lucasfilm production, Johnson worked on The NeverEnding Story (1984) and James Cameron's Aliens (1986), for which he won a BAFTA for visual effects (shared with Robert Skotak, John Richardson and Stan Winston).

Asked if he had any favourite projects, he replied, “There are loads of favourites. Obviously 2001 because, for me, that was a leap in my experience of doing movies, and working for top-rate directors, art directors and camera people.” Other favourites include The Empire Strikes Back, Alien and Dragonslayer as “they were all good fun to work on.”

Johnson’s advice to others entering the profession is to get everything prepared beforehand as much as possible and having made the decisions, to stick to them.

Asked how long it took to learn about special effects, Johnson said, “You learned as you went along.” And which film proved the most difficult? “I think The NeverEnding Story, shot in the English language in Germany. There were a lot of complicated motion control and effects shots. We built the world’s largest blue screen too, 35m x 18m.”

Recalling some of the cinematographers he worked with, Johnson said, “They include Paul Beeson, Skeets Kelly, Douglas Slocombe, Freddie Young and Peter Macdonald, who went on to direct. He is one of the best camera operators I ever worked for. He’s an incredible cameraman and camera operator. In fact on Dragonslayer, the picture I did after The Empire Strikes Back, the camera work was some of the finest I’ve seen.”

Although Johnson has provided his services to a multitude of film and television productions for over 40 years, he’s not retiring just yet. He will shortly be directing a series of short films for children called Dream Street. He is also lined up to work as special effects supervisor on The Entwined, directed and produced by Rob Hollocks, which he says will be in the Hammer style of horror.