Overview: Requiem is set in 1605, against the backdrop of the witch trials. It’s a coming-of-age story, following Evelyn as she engages in a game of cat and mouse against her father, Minister Gilbert, in order to be with Mary, the woman she loves.

What were your initial discussions about the visual approach for the film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

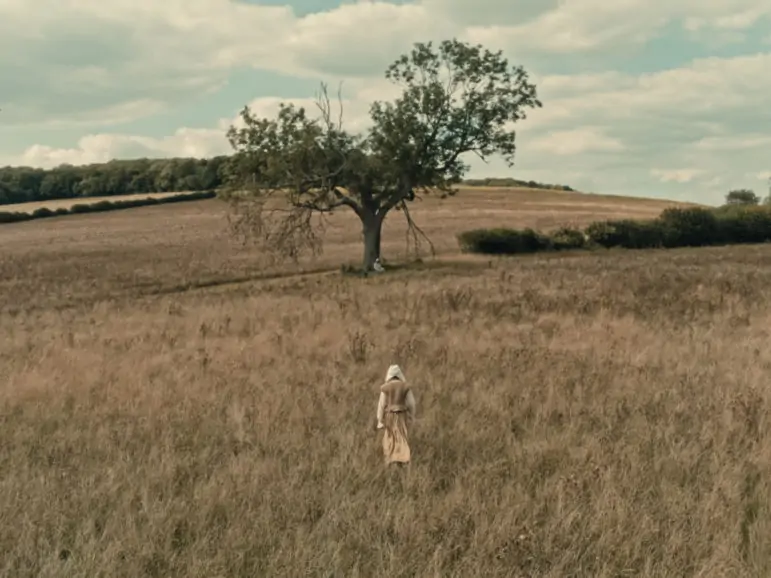

Along with director Emma Gilbertson, our aim was to strike a balance between a naturalistic look, and something more ominous with a heightened atmosphere. Requiem is a story set in a specific time in history, and I wanted the image to embody that. The overall goal was to strip away anything that would feel too modern. This idea determined many of the cinematographic decisions. We didn’t want the film to feel like it was made in the past, but a timeless window that teleports us into the past.

My instinct was to minimise camera movement or anything too kinetic to allow the images to feel heavy and oppressive, personifying the internal experience of our lead character Evelyn. I chose a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, to add weight to the image, and allow more headroom above Evelyn, making her appear vulnerable in frame. For the lighting, I wanted a good amount of contrast for the interior work, keeping it fairly low-key, allowing the background and corners of the frame to fall-off into darkness. For the exteriors, the intention was for a consistent overcast gloom, with exceptions for when Evelyn and Mary are together. Then it should feel more optimistic, with a richer palette and a brighter glow to the highlights.

What were your creative references and inspirations? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

I drew inspiration from a variety of paintings, most notably Rembrandt’s Philemon and Baucis, which has such a warm and beautiful low-key glow to the lighting. This really inspired my approach to the candlelit scenes. In regard to film influences, Haneke’s The White Ribbon, Pawlikowski’s Ida, and Bela Tarr’s The Turin Horse all had an effect on me during prep. These films all have a certain mood and energy that I really connected with in terms of lighting, composition and pacing. They aren’t afraid to hold on a frame. Many of the film references were black-and-white and we did play with the idea of going that direction. However, fire was an important element to the story, and therefore felt that colour would play an important role in the story.

What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed? Did any of the locations present any challenges?

Finding and securing the right locations was the toughest part of pre-production, especially as it was during the first COVID lockdown in the UK. We were really striving for authenticity and building a world that felt real. Early on, we agreed that shooting on location would provide more scope than anything we could build. Production designer Freddie Burrows dove deep into his historic research and found a selection of churches for us to recce that had the right look and authenticity for story. Initially our best option was to separate the interior and exterior between two different churches. But due to time and budget we had to figure out a way to combine them into one location. We settled on St Mary Magdalene’s Church, Boveney, which in hindsight, was one of the best decisions we made.

In terms of locations, the minister’s house is the nucleus of the story, and became the most crucial location for us to find. The only houses that hadn’t been modified over the centuries could be found in museums. The Medieval Town House at the Avoncroft Museum, Bromsgrove, had the right look but it was around 150 years too early for the films setting. So Freddie came up with the solution of building a Tudor style fireplace into the structure and adding doors and furniture to bring it from the mid-1400s up to the early 1600s.

We also shot the interior and exterior of a beautiful 15th century barn at the Chiltern Open Air Museum, as well as a handful of exterior locations scattered around Buckinghamshire to tie the world together. It was a real schedule nightmare fitting all of these locations into an eight-day shoot, but we knew it would be totally worth it.

Can you explain your choice of camera and lenses and what made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

Honestly, I would have loved to shoot Requiem on 35mm film as I think film has an organic and textural quality that would have lent itself well to the story. However, due to the 4×3 aspect ratio, shooting 4-perf 35 was out of the question in terms of budget, and I wanted more resolution than 16mm. We quickly realised that the film would benefit overall from shooting digitally. My go-to digital camera has always been the ARRI Alexa, in particular the Alexa Mini. I have built a relationship with that camera over the years and it gives me everything I need to design a unique look for any project. I paired the Mini with Cooke S5s. I’ve always been a huge fan of Cooke lenses. They are sharp but maintain a smooth roll-off that I love, and a subtle warmth that fitted nicely with Requiem’s palette. I went with the S5s as I knew I would need the extra stop for the candlelight scenes where I wanted to supplement with as little light as possible.

What role did camera movement, composition and framing and colour play in the visual storytelling?

Like I mentioned, we were very sparing with camera movement, utilising it only for specific moments when more energy was needed in the scene. The overall stillness heightened the moments where more movement was brought in. This is most evident in the scene when Evelyn and Mary are caught. We are entirely handheld for the first time, which really builds suspense, adding more energy and anxiety throughout the scene.

Compositions always had to feel balanced and centered around Evelyn, keeping lines parallel, almost caging Evelyn like a prisoner within the frame.

Colour played a huge part in building the look for the film. In terms of lighting, colour was always very natural, either daylight or firelight. However, I wanted the fire to have an intensity to it, allowing the colour to engulf the frame, foreshadowing the events to come. Overall, we aimed for a unique colour palette. There is a drained, yet warm patina to the image that evokes hope but is never too optimistic.

What was your approach to lighting the film? Which was the most difficult scene to light?

The overall philosophy was to keep the lighting as simple as possible. As the story’s set in the early 1600s we were dealing with only sunlight, moonlight or candlelight. The location for the minister’s house was a real delight to work in. It had small medieval windows with wooden shutters that allowed us to control the natural light quickly and easily. For the day interiors we bounced Panalux’s P-Series 4K + 1.8K’s into 12x12s outside the window to maintain a soft and consistent day light. Within the space we used smaller HMIs, Astera tubes, and a SkyPanel, either bounced or through diffusion to supplement and shape the light coming in from outside. For the night interiors, we stripped it right back using only candlelight where possible. We placed double-wick candles as practicals in frame, using additional candles off-frame to fill and supplement. Occasionally we brought in an LED Springball overhead to set and ambient level to maintain detail in the shadows.

The most challenging scene to light was the pyre burning scene. It was written for dusk which I knew would be a challenge as we had only one evening to shoot a dozen or so shots. My initial idea was to shoot the scene with two cameras, capturing the wides while the light was right, and supplementing the close-ups in the dark. But luck wasn’t on my side. Thunder and lightning rolled in, putting everything on hold, pushing us back a couple of hours. I lost my window of natural light and only had a few hours to rethink the scene with the little lighting we had, and attempt to keep everything looking consistent. It was definitely a steep learning curve.

What were you trying to achieve in the grade?

Although we chose not to shoot in black and white, I was still influenced by a desaturated and subdued palette with rich, inky-blacks. I worked closely with colourist Marco Valerio Caminiti who developed a unique LUT that really orientated the look of the film onset. We went for a warm palette, dialing the blues and greens right back, which complemented the earthy, woody tones of the production design and costumes. In the grade we really fine-tuned this look, and ramped up the texture, adding film grain and dirtying up the image to embody the rural lives these characters led.

Which elements of the film were most challenging to shoot and how did you overcome those obstacles?

Making a period film with limited budget, during a pandemic was always going to be a challenge. Crowd scenes had to be re-considered and even simple blocking was tough due to mask wearing and social distancing restrictions. In terms of world building, the exterior of the house posed lots of challenges as other buildings of different eras were scattered around the museum. This limited the angles we could shoot and persuaded us to think creatively. In the script, the minister’s house and the church are next to one another. So to combine the two together we shot in one direction at one location and matched it to a reverse shot at the other, creating a new sense of geography. Matching weather conditions was a huge risk but I think we just about got away with it.

What was your proudest moment throughout the production process or which scene/shot are you most proud of?

In terms of my own work, I’m most proud of the interior scenes we shot in the minister’s house. The incredible location along with the stunning work from the art department made my job easy, and a joy to light. Overall, I’m extremely proud of the whole team pulling together and achieving what I think is an incredibly ambitious film, with many challenges stacked up against us. The hard work and dedication across all departments was phenomenal. It was an experience I feel really privileged to have been a part of.

What lessons did you learn from this production you will take with you onto future productions?

Not to attempt shooting a whole scene at dusk! In general, I learnt a lot about natural light and scheduling exterior scenes around light. I have a much greater confidence at geographically deceiving the audience through what I show in the frame and what I decide to leave out. And finally, this project has affirmed my philosophy that less is more when it comes to lighting and the type of cinematography I love and aspire to make.

> DISCOVER MORE ‘FICTION’ FILMS FROM THE 2021 NFTS GRADUATE SHOWCASE

> GO TO BRITISH CINEMATOGRAPHER ‘HOME’ PAGE

> BACK TO TOP