MASTERCLASS IN MONOCHROME

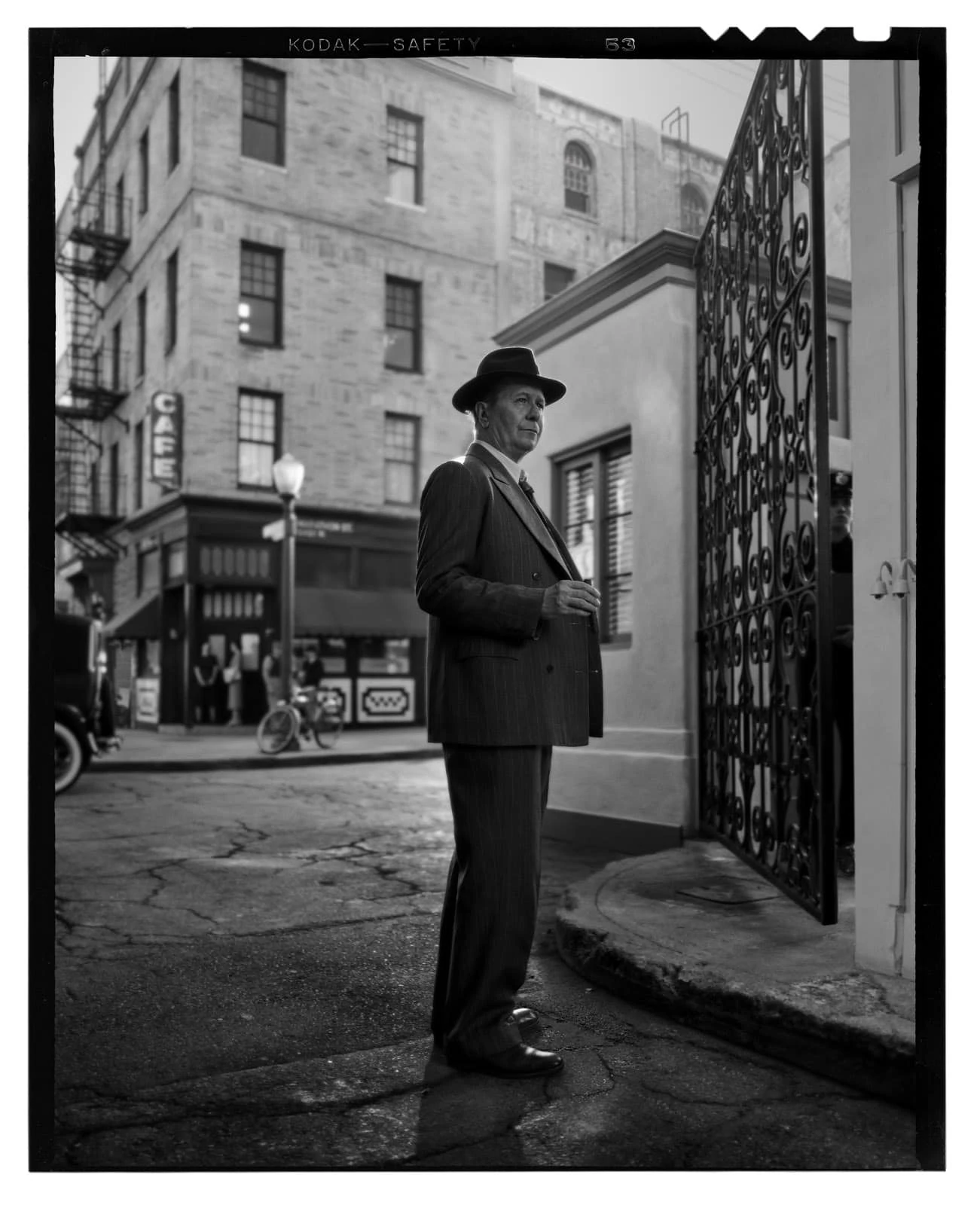

Black-and-white biopic Mank sees another successful collaboration between cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt ASC and director David Fincher as they craft an authentic portrayal of Hollywood’s golden age and explore the turbulent development of the script for Citizen Kane.

“This was not an offer I had to consider; the answer was an immediate yes,” says cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt ASC when thinking back to the moment he was asked to film director David Fincher’s Mank which depicts the life of screenwriter Herman J. ‘Mank’ Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) as he develops the script for director Orson Welles’ 1941 classic Citizen Kane.

“I was thrilled when David called me,” he says. “I was nervous too of course as I felt a tremendous responsibility to be considerate and respectful to the film, but it’s a cinematographer’s dream to get the opportunity to make a movie like this.”

As Citizen Kane is widely regarded as one of cinema’s masterpieces, the pressure was on to capture the essence of Gregg Toland ASC’s cinematography and to faithfully encapsulate the distinctive mood, lighting and composition reminiscent of a golden era of filmmaking.

Mank, which received a limited theatrical release before streaming on Netflix, is based on a script written by Fincher’s late father, the journalist and writer, Howard “Jack” Fincher which focuses on the controversy surrounding who had creative ownership of Citizen Kane – Welles or Mankiewicz.

The film uses flashback sequences to explore the prolific talent of Mank as well as his alcoholism and tumultuous relationships with Hollywood executives such as film producer and MGM Studios co-founder Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) and Irving G. Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley) and publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), who is widely claimed to be the inspiration for Citizen Kane’s protagonist.

Fincher was clear from the beginning that the film would be shot in black-and-white. “We never even considered what the movie would look like in colour,” says Messerchmidt. “Part of David’s intent was to transport the audience back to the classic ‘30s and ‘40s Hollywood era. Black-and-white was an excellent way to do that.”

Ensuring black-and-white was used as a homage or a pastiche rather than a parody was a priority. “When they approach black-and-white, cinematographers can tend to reach for noir as they are excited by its gestured, stylised lighting which you don’t get to use very often when shooting in colour,” adds Messerschmidt.

Working in black-and-white, we found we had to be a little more exotic with the colour choices to achieve enough separation and tonal variants.

Erik Messerschmidt ASC

Although a noir approach also came to mind when the cinematographer learnt he would be lensing Mank, once he read the script Messerschmidt realised it would not be a noir film: “I had to reorient myself and think about the film stylistically from the script perspective, which a cinematographer should always do.”

To guarantee visual choices were dictated by the narrative, Messerschmidt broke the script down into stylistic beats, thinking about the film from the perspective of an editor as much as a DP. “I considered how the shots would work together in context, how sequences would be built and how to tell the story with the camera. David and I have a similar aesthetic sensibility – we think about cinema, sequencing and how to break coverage down in the same way which means we come to conclusions quickly.”

Initial preparation included conversations with costume designer Trish Summerville, production designer Donald Graham Burt and set decorator Jan Pascale. Colours, tones and fabrics were extensively tested to assess how they would be rendered on camera.

“David is not a director who generally embraces lots of saturated colour. On previous productions we’ve worked in a muted palette with a very specific set of colours and in many cases nuanced shades of the same colour,” says Messerschmidt.

“Working in black-and-white, we found we had to be a little more exotic with the colour choices to achieve enough separation and tonal variants. You could walk on the set and the extras would be dressed in very contrasting outfits and colours we would not normally have chosen – rose or saturated red, purple or teal green.”

To develop Mank’s aesthetic, Messerschmidt compiled a look book for Fincher to view, comprising around 300 images including contextual visuals appropriate for specific scenes. References came from the whole canon of black-and-white photography; from early ‘30s glamour through noir to more modern imagery and black-and-white films such as Night of the Hunter (1955), Casablanca (1942), The Apartment (1960), The Big Combo (1955), In Cold Blood (1967), Manhattan (1979), and Good Night, and Good Luck (2005).

Prior to shooting Mank, Messerschmidt was in South Africa filming Ridley Scott’s sci-fi series Raised by Wolves which meant he was not heavily involved in the early location scouting process. “Don Burt and David found most of the locations before I started work on the film. We then assessed them from a practical perspective and made a few small changes. Some locations were difficult to source such as the synagogue where we shot producer Irving G. Thalberg’s funeral. We just couldn’t settle on this until we started shooting and eventually found a location that worked,” he says.

Despite locations initially being scouted for interior scenes in Hearst Castle – William Randolph Hearst’s estate – it was not possible to hang lighting equipment where required within the space, so these were built on stage.

Exterior shots of the bungalow in which Mank writes Citizen Kane were filmed in the actual location he penned the script, while the interiors were stage builds. Major studio lots in Los Angeles including Paramount, Sony and Warner Brothers provided the perfect settings for the scenes exploring the backlots of Paramount and MGM.

Stylistic devices

Although he is a fan of film’s qualities, Messerschmidt knew digital was a better fit for Fincher’s workflow. “There are those happy accidents when you shoot with film, but there are also unhappy accidents. David likes to previsualise, so film would have been the wrong choice, but we explored how we might emulate certain characteristics of film when shooting digital.”

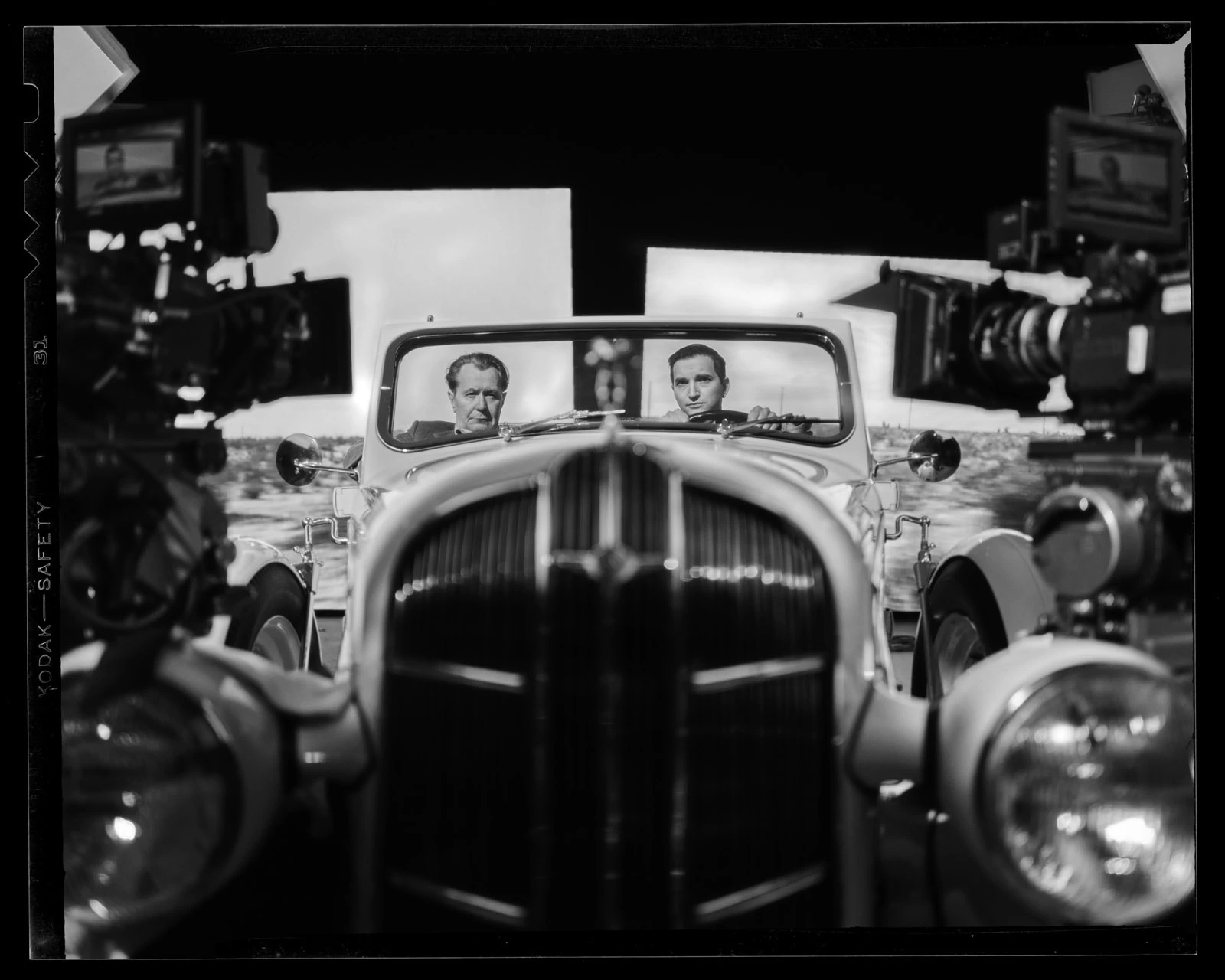

To pay homage to films of the era and reference Citizen Kane specifically, stylistic devices such as deep focus were adopted. The photographic and cinematic technique – which uses a large depth of field so the foreground, middle-ground, and background are in focus – was deployed extensively by cinematographer Gregg Toland when he lensed Citizen Kane, as were low camera angles, which were also used in Mank to add authenticity.

Messerschmidt carried out extensive lens, camera and filtration tests and had conversations with Fincher about when was appropriate to use deep or shallow focus, which parts of the story would motivate that choice and which locations would work best. “Weeks of testing were needed to decide which lenses would perform best at the stops we required. It turned out most lenses did not perform particularly well,” he says. “I thought large format lenses would be best but most fell apart and lost all resolution on the projector above a T8, even the sharpest lenses.”

Having experimented with a variety of lenses at Panavision and then Keslow Camera in Los Angeles, Messerschmidt found the Leica (now Leitz) Summilux-C offered the best performance in terms of resolution because the iris is physically smaller at T8 and produced more apparent depth of field at the same stop as other options he tested. “This meant I could shoot at an eight but achieve the same depth of field as an 11, but with greater resolution. David and I had already shot with the Leica for several years and it’s proven to be incredibly reliable.”

There are certain scenes in Mank for which the director and DP deliberately decided not to use deep focus. “We used a cmotion Cinefade variable ND filter to achieve depth of field pulls, where we would start with the entire frame in focus and then collapse depth of field and end with someone in focus and the rest softer, or vice versa,” Messerschmidt explains.

“The hope was that it would be enough of a reference to movies of the period while still featuring elements of modernism. Obviously, the aspect ratio is not period correct, but we were not expecting people to think they were watching a movie made in the 1930s.”

Messerschmidt shot most of the film – including all exterior scenes – using a Harrison Orange 2 filter as it achieved the required tonal separation between skin tones and backgrounds. “When shooting faces, the result was really impressive, especially lips and eyes,” he says. “We carried out make-up tests – hundreds of lipstick tests for Amanda [Seyfried] – to find the right one because just the wrong shade of red would turn black very quickly.”

The cinematographer initially tested colour cameras, thinking shooting colour and converting in post might be the best approach for Mank. “I also talked to Phedon Papamichael about his experience shooting Alexander Payne’s black-and-white film Nebraska (2013). He shot colour and then desaturated it, which most cinematographers have been doing in the digital age,” he says.

Although his initial feeling that the colour information in the negative would be helpful when isolating colours and adjusting tonal values in the DI process, Messerschmidt later discovered obstacles that would need to be overcome. “I knew when adopting the deep focus technique, I would need to light the set to a T8 or T11, which even at 800 ASA is challenging. We had a good schedule, but we didn’t have 100 days to shoot the movie.

“David also values spending time with his actors more than anything, so I couldn’t take two hours to light the set or spend hundreds of thousands of dollars lighting them. Therefore, I needed the fastest camera I could find.”

Messerschmidt and Fincher shot colour and black-and-white tests and compared them in the grading suite. They were pleased with the colour test, but when they saw the test footage shot using a camera with a black-and-white sensor they knew that would be the best approach. “Just seconds into the screening we knew the black-and-white camera was superior. It just looked better, with more tonal depth and dynamic range to it. The colour camera felt flat and thin by comparison. It was an easy choice.”

The search for the fastest camera that would be most suitable to shoot black-and-white and achieve the desired deep focus effect led Messerschmidt to the RED Ranger Helium Monochrome 8K camera.

“Large format didn’t seem appropriate,” he says. “The RED Monstro or ARRI Alexa Monochrome cameras were considered, but we needed a Super 35 size sensor for depth of field.”

Mank was shot in 8K, followed by a 20 per cent centre extraction to produce a 6.5K raster. The grade was then completed in 6K and the conform was finished in 4K.

When shooting crime series Mindhunter with Fincher, Messerschmidt monitored on set in HDR in Dolby PQ which has since transformed the way he works. “Now, even when I shoot an SDR project or something destined for standard dynamic range, I insist on monitoring in HDR because I get better exposures,” he says.

Messerschmidt repeated this process for Mank, monitoring the black-and-white footage on the Canon DP-V2411 HDR reference display at 600 nits. “We built LUTs in Dolby PQ and then took the RED log and transformed it to Dolby PQ before doing the HDR finish in Dolby Vision,” he explains.

Creative collaborations

Although Fincher does not typically move the camera unless actors are moving, the long walk and talk scene which sees Mank and Louis B. Mayer walk through the studio lot is singled out as one of Messerschmidt’s favourite uses of camera movement in the film. “It’s just two long tracking shots,” he says. “Dwayne Barr, the dolly grip we’ve worked with for the past few years was fantastic and was such an artist in that scene.”

The scene in which William Randolf Hearst escorts Mank from his residence was shot with three cameras simultaneously. “We built a sort of sled dolly for the cameras with an M7 Evo stabilised head in the centre and two DJI Ronin gimbals on either side. This allowed us to shoot three pieces of coverage at once which David could then undercut,” says the cinematographer.

Messerschmidt found working with more light on set an interesting and enjoyable challenge, a process that was enhanced by a close collaboration with another member of the Mindhunter production collective, gaffer Danny Gonzalez. “Incorporating that amount of light is not appropriate for everything, but it was nice to have the opportunity to work that way again; to have to really use a light metre and work with big sources and lots of lights,” says the DP, who was a grip and gaffer for features, TV and commercials before making the move to cinematographer on Mindhunter.

“I had done gestured, stylised cinema lighting before, but nothing like this recently, where I really had to lean on older lighting techniques. Mank is a combination of those older, hard light techniques of the ‘30s and ‘40s which we used for the flashbacks as well as the more modern naturally or practically lit interiors.”

To make the 1940s “present day” scenes that were not in flashback appear more modern, soft top light was used, creating less contrast. Atmospheric interior scenes in the bungalow where Mank writes the script were shot using smoke and shafts of light primarily coming through the windows, along with ARRI T12 12K incandescent fresnels, Kino Flo FreeStyle soft light fixtures, ARRI Sky Panels and LiteGear LiteMats as subtle front, fill or top light.

“At those sorts of stops we were still using 200-300 foot-candles on the set which helped keep light off the back wall and limit the amount of light in the room. Shooting at those deep stops, things just fall off differently, so this meant I didn’t have to be quite as controlled,” he says.

Virtual production techniques were adopted with great success to create realistic environments for a selection of scenes including driving sequences, the meeting on a bench between Mank and Hearst’s mistress, actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) and when Mank and his wife Sara Mankiewicz (Tuppence Middleton) are on a ferry. These were filmed at Fuse in Los Angeles using a virtual set comprising ROE Visual’s Black Pearl 2.8mm LED.

“I’ve worked with Fuse extensively in the past, having filmed sequences for both seasons of Mindhunter and commercials with them,” says Messerschmidt. “Fred Waldman, the lead technologist, is a real creative partner of mine.”

Mank also saw another repeat collaboration, between Fincher, Messerschmidt and colourist Eric Weidt, who they teamed up with on Mindhunter. “He works in-house at David’s office which is fantastic because we have full access to him,” says Messerschmidt. “He was on Mank from the beginning of prep, so he played a big part in helping me design the LUTs, especially for the day for night work we did for the Marian and Mank nighttime walk and talk scene through Hearst Castle which was all shot in the middle of the day.”

With Weidt on board from the production’s inception, all testing Messerschmidt and Fincher carried out went through his grading suite. “This meant we could get really practical and dig deep into the quality of the negative to figure out how much to overexpose and how close to the highlights I could get to make sure he had room in the grade,” says the DP.

The colourist also helped Messerschmidt develop the HDR viewing process and workflow, add film grain and ensure the movie was reminiscent of productions shot on film during the period by emulating gate weave – the shake that can occur when film rolls through the projector.

“Eric also played a crucial role in achieving an effect we called the black bloom which is a reference to something that happens with black-and-white print stops when you print, producing subtle black halation in the shadows. It’s really unique and almost looks like you’re diffusing the shadows,” says Messerschmidt. “We grabbed the shadows, keyed them and blurred them slightly in the grade to achieve an unusual, glossy look.” Reflecting on the filmmaking process and the multitude of effective partnerships at its core, Messerschmidt adds: “It was also just a pleasure to work with a crew and cast of that calibre. It was a sad moment when the production ended because it was one of those special movies we really enjoyed creating.”