WITHSTANDING THE PUNCHES

The Fire Inside battles through production delays and technical challenges, with Rina Yang BSC capturing Claressa Shields’ rise using dynamic lensing, natural lighting and cinematic realism.

Having to take a few punches was The Fire Inside as the Amazon MGM Studios movie had to shut down because of the pandemic and then readjust its footing when a scheduling conflict meant that a new cinematographer had to be recruited. It was like art intimidating life for the sports drama that follows the struggles of middleweight boxer Claressa Shields to become a two-time Olympic champion and the less than glorious aftermath she had to overcome. The script was written by Barry Jenkins and is the feature directorial debut of Rachel Morrisson ASC who previously helmed episodes for The Mandalorian, American Crime Story and The Morning Show. She is also known for being the first woman to be nominated for an Oscar for Best Cinematography which did not cause any additional pressure for Rina Yang BSC when she joined the second round of production.

“People often ask me that question,” states Yang. “But I didn’t feel the pressure because Rachel was very welcoming.” What was difficult was the preproduction period due to the logistical complications and challenges. “They had shot for two days [before shutting down] and we had to do it all over again. Rachel had to do the prep twice. We joked how hard the preproduction was on this movie. We were doing 12 hours longer everyday prepping. Some movies you have much less intense prep.”

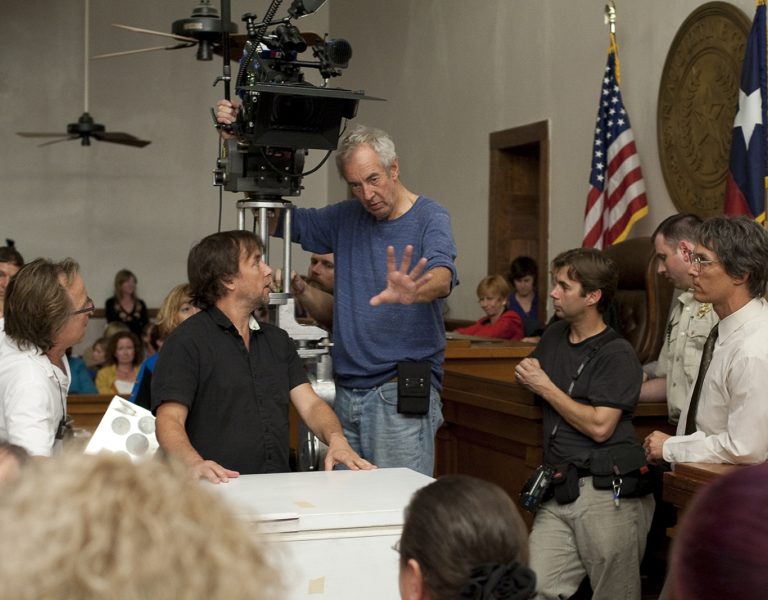

Two important lessons were learned from collaborating with Ryan Coogler on Fruitvale Station and Black Panther. “One of them impacted my decision to hire Rina which is surrounding yourself with different visions and ideas, and letting everything be a conversation,” says Morrison. “Ryan also likes to be close to the actors and sometimes doesn’t even look at the monitor. Fortunately, one of the beautiful things about Rina is that there were many times when I could operate the camera and that allowed me to be in the space naturally. When I wasn’t operating, I would duck down next to the camera.”

The PBS documentary T-Rex: Her Fight for Gold was a point of reference. “I loved the documentary which was inspirational and beautiful,” says Yang. “Rachel and I talked about the cinematography that we liked and sent each other a list of films. We had similar tastes.”

The story of Claressa Shields is remarkable but not widely known. “If I’m going to make a biopic, I’d rather make it about someone who deserves to have their story known and it’s incredibly relatable,” says Morrison. “She’s a model of resilience and incredibly inspirational. You’re not watching Elvis but the best version of yourself.” Morrison empathises with Shields. “For Rina and I, there were a lot of similarities being a female DP in this incredibly male world. It’s not enough to be good at what you do. You are always viewed through the lens of being female. There are all of these extra hoops that you have to jump through. I can see myself in this story through a different lens.”

PICKING FIGHTS

In order to see how the entire movie flowed from beginning to end a shot list was devised. “We didn’t have rigid rules,” explains Yang. “We would talk about how we would want to shoot the scene and what we want to get out of each fight. For example, for the first one we see we did a oner because it felt like the right moment to do it. In the Olympics, we are inside and outside the ring.”

The same approach was adopted with lighting. “Shanghai was a lot of LEDs and for the Olympics we had PARs rigged around as well some moving lights. In the middle, the soft box was LED because of the colour shifting capabilities. Maybe this fight can have more flare and that one can be less. We were conscious of not trying to repeat ourselves so you don’t get fight fatigue as an audience.”

Storyboards were created sparingly. “We would only storyboard if there was a huge visual effects or action sequence so that we have a communication tool and can look at it,” says Yang. “We could also use it as inspiration.”

Narrative and dialogue scenes were treated differently. “We all come with ideas of how we see the scene, then see how the actors do it in the space, and modify our shot list.” It was always important to retain the subjective perspective of Shields and her coach Jason Crutchfield which impacted the lensing. “If you have someone you care about watching from faraway which we did, Jason couldn’t get close to her in the ring so that is why we would use a long lens,” notes Morrison. “But to just shoot people with long lenses from halfway across the room for no reason, it always feels like an objective style of filmmaking.”

Guiding the visual language was a specific question. “What is Claressa feeling in this moment?” says Morrison. “It’s not only about is she winning or losing? What does it feel like to be fighting without the coach you have trained with your whole life? How do we photograph that fight in a different way than when you’re fighting with your coach by your side?”

One particular aesthetic was avoided. “We never wanted it to feel like a documentary,” explains Yang. “We did want to run around with the camera. It’s more like breathing with the character. We did go for 29mm because it felt we were shooting close to them.”

The lighting is somewhat naturalistic. “Rina did a lot of tone pull and a more poetic lighting,” states Morrison. “There is a cinematic realism which is different from a documentary.”

Some of the lighting schemes were imposed by the locations. “The place we found for the Shanghai venue had a lot of LEDs there and we had a lot of restrictions,” reveals Yang. “I couldn’t rig any top lights.” Then there was the matter of how the environments should be portrayed. “2012 Flint, Michigan is analogue so we did things with tungsten sources,” states Morrison. “It’s low-fi there. We wanted Shanghai to feel modern, different, and new so we went LED and were more colourful.” Four LUTs were created and pared down to two. “One had a bit more contrast and the other was lower,” remarks Yang. “We worked with Joseph Bicknell at Company 3. I did want to play a little on set because one of our cameras tended to be magenta so I had a LUT called Flint De-Magenta which was our hero LUT! But we didn’t jump around too much.”

TECHNICAL KNOCKOUT

Camera of choice for the production was the Sony Venice with the Rialto. “Because of how we felt the film should be shot, in particular the fights, it felt like we would benefit a lot from the Rialto.” The fights leading up to the Olympics utilised two cameras. “One might be a long lens to catch the audience and other details while the A camera would be on Claressa. Then for the Olympics we had five to six cameras and mostly a single camera for any dialogue scenes. We often tried to wedge two cameras, however, sometimes it doesn’t look right because one of them feels so removed.”

Panavision altered the original lenses to suit the Sony Venice camera and Rialto. “We modified the Panavision Panaspeeds to lower the contrast a little bit more and also modified the colour of the flare to be warmer,” states Yang. “I like a little halation in the highlights and talked to Panavision about it being great not to put the filter in the lens so I could shoot clean with the internal filters of the Venice. We ended up adding more for the wide lenses. On the day we would put the glass in front of them.” The longest lens was 135mm. “Our hero lenses were 29mm and 40mm. We only used long lenses when shooting outside of the ring. There were some lightweight zooms on the other cameras, and I would pull the zoom from the DP station.”

Shooting 2:39:1 was always the intended aspect ratio. “I wanted the scope of a widescreen because it’s such a two hander, in regard to the relationship between Jason and Claressa,” says Morrison. “Even if it’s for the sake of an over the shoulder.” Having the stamina to shoot fight after fight was hard. “You’re trying to be mindful of not exhausting the talent and getting the shots,” says Yang. “Technically we didn’t do any fancy body rig. We did the oner where we were pushing in on the crane, detached the camera and the operator would get into the ring. Rachel also makes a cameo so she could talk to Ryan Destiny [plays Claressa Shields] by the ring. That was fun.” The oner was the most complex shot. “The camera move wasn’t that complicated, but it was the choreography of all the people involved,” remarks Morrison. “No one could miss a beat.” Yang adds, “It was a dance and we did 17 takes.”