GREAT VISTA

Lol Crawley BSC and director Brady Corbet explore architectural ambition and human conflict in The Brutalist, captured in the rare VistaVision format for breathtaking visual storytelling.

As far back as the shoot for 2018’s Vox Lux, Lol Crawley BSC was made aware of his next collaboration with writer-director Brady Corbet. “We wrapped in a parking lot in New York on a night shoot, and Brady swung around with this book on Brutalist architecture,” says the British-born cinematographer, brandishing a copy of Peter Chadwick’s tome This Brutal World when we speak over Zoom. “And he said, ‘This is the next one.’”

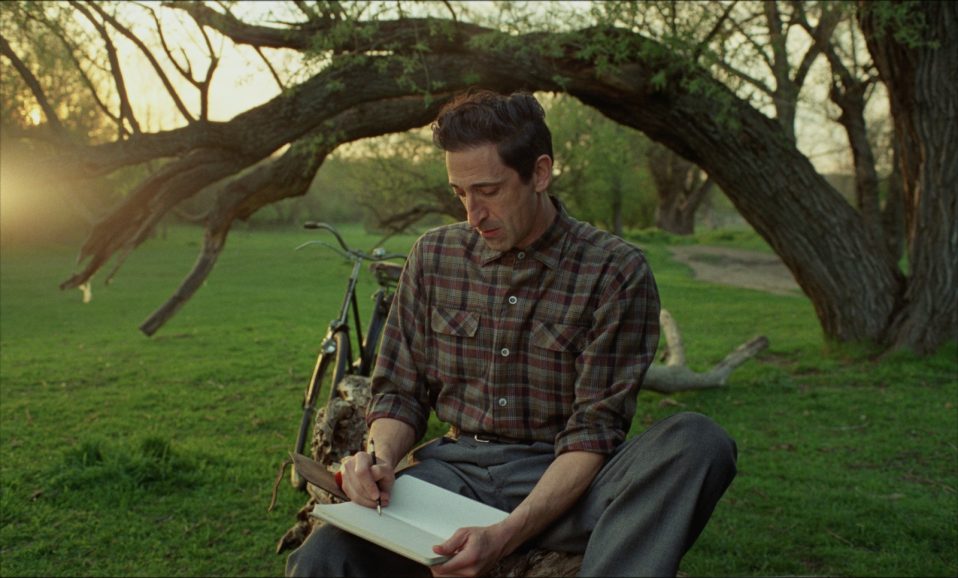

By which Corbet meant that he and his writing partner Mona Fastvold would conjure a film inspired by the architects coming out of the Bauhaus movement. The result is The Brutalist, an epic that spans decades as it follows the life of László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a (fictional) Hungarian-Jewish architect who arrives in postwar America to undertake a wildly ambitious project for business tycoon Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), while also navigating the safe passage of his wife and niece from Europe.

Corbet was very comfortable returning to work with Crawley, who had also shot his 2015 directorial debut The Childhood of a Leader. “We have very similar sensibilities,” says the director. “I mean, we really finish each other’s sentences. I think that we have a very special partnership, and we do very special work when we come together. And we have a shorthand, because we’ve done it on so many projects.” Even so, the work they achieved on The Brutalist – which won Corbet Best Director at the Venice Film Festival, where it premiered – is nothing short of monumental.

Crawley suggests that Corbet’s film harks back to an earlier era of filmmaking, citing in particular Orson Welles’ character study supreme Citizen Kane. “It’s big, it’s bold,” he says of The Brutalist. “It’s dealing with really interesting issues, certainly that are relevant to this time as well, in terms of immigration and the contrast between old world aesthetics and a certain classicism and modernism that was coming out of Europe after the Second World War.”

In keeping with this, Corbet insisted on shooting The Brutalist in VistaVision, the format that was pioneered by engineers at Paramount Pictures in 1954. “It’s very, very exciting to use it,” says Crawley, who reports that Corbet had been plotting to work on larger formats ever since Vox Lux. Specialist suppliers Camera Revolution provided the VistaVision camera, which was then prepped at camera rental company Movietech. But as Crawley points out, there were a number of technical challenges to overcome.

“The first thing is, there just aren’t that many of them,” he says. “Obviously, if you have a [modern] camera and there’s an issue with it, you can make a phone call and get it swapped out, and you get another one. That’s hard when you don’t have that kind of resources or support. So it’s a little bit like working with an antique in that regards.” Other issues included a camera eyepiece that was tricky to use and the machine’s noisy innards. “But the potential for the photography is so fantastic that it outweighed the challenges.”

Expanding horizons

A higher resolution, widescreen variant of 35mm stock, VistaVision is an “extraordinary format”, says Crawley. “Essentially it’s over twice the neg area, so your resolution and field of view increases.” He says it was perfect for capturing some of the film’s more impressive landscapes, including a scene at the marble quarries in Tuscany. “Normally, if you wanted to shoot those, you’d shoot on a wider angle lens to achieve that. With VistaVision, you don’t need to, because the field of view is wider. I mean, the clue’s in the title with VistaVision…it’s beautiful for these vistas.”

Corbet was determined to shoot on VistaVision, making The Brutalist the first full American VistaVision feature in more than six decades. But he concedes that it was not easy to justify to the producers and financiers that he wanted to deploy an antiquated format most famously used for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo and North By Northwest. “It’s been a lot of sacrifice to make it happen,” he says. “But we’ve never been obliged to make a movie on another format. And, for me, the thing is that I just want to take a tool out of the box.”

The director is a fierce advocate for celluloid. “I don’t think people realise how close we have come, on multiple occasions, to never having celluloid ever again,” he explains. “I mean, keeping the lights on in the factory in Rochester that manufactures celluloid is not cheap. Fortunately, I feel like there are just enough people who are working with celluloid, especially in adverts, because in advertising, the point is just to make it look as good as possible. So they’re willing to spare no expense to sell their product.”

While Corbet underlines that celluloid and digital “yield very different results”, he is not against using digital. “There are many digital films that I think are stunning. We would not have a film that is as formally daring as The Zone of Interest if it weren’t for these digital technologies. But I think that, especially if you’re shooting a period movie, it just makes sense. It just transports you. It’s the difference between streaming a piece of music and listening to it on vinyl. It’s a different experience.”

Indeed, it felt an appropriate way to capture a film that spans a time period when VistaVision was in vogue. “I was definitely thinking about a way of evoking the 1950s by not only shooting on a camera from the 1950s but also staging it in a way that would be evocative of those films,” says Corbet. “I feel a responsibility to filmmakers from a bygone era to try and go just a few steps further than they were allowed to. Man is a bridge, not a goal. In terms of radical cinema, you usually are only allowed to take a couple of paces forward.”

Not only does the use of VistaVision evoke the movies of the past, but its wide, rectangular shape also helped convey the essence of Brutalism, the architectural style at the heart of the film. While the film’s protagonist Tóth notes that he trained at the Bauhaus, the school of design established by Walter Gropius in Germany in 1919, his passion is for Brutalism, the minimalist postwar style that favoured function over form, often using large blocks of concrete and steel to craft its designs.

To aid this, Corbet turned to production designer Judy Becker, whose distinguished career has seen her work with such acclaimed filmmakers as Todd Haynes, David O. Russell, Ang Lee and Lynne Ramsay. Becker’s most complex task was creating the heavily symbolic Institute that Van Buren commissions Tóth to work on. Given the film’s budgetary limitations, it was never going to be possible to build such a grand folly in its entirety.

“Brady had said to Judy Becker very early on, we’re not planning on building the Institute, because obviously it’s a huge subterranean concrete piece of Brutalist architecture,” says Crowley. “So really it was pieced together through a number of found locations within Budapest. For example, there are these beautiful cylindrical concrete silos where the altar-piece is installed. That was one place that Judy then added to.” VFX was also cunningly used to help recreate the site, one whose designs alluded to the concentration camps to reflect Tóth’s own experiences of captivity.

Another of the great collaborations between Becker and Crawley comes with the library that Tóth first designs for Van Buren. “László designs this modernist library with all of the doors fanning out together, which was a beautiful piece of design from Judy,” says Crawley. In the narrative, the library’s old-fashioned glass ceiling dome is removed and replaced with a more modernist aperture, allowing for an almost spiritual moment when the light hits the glass. Shooting it in VistaVision, “you had this larger-than-life field of view and this image, and then the light pouring down through this aperture,” says Crawley. “So I was really, really happy with how that turned out.”

For the lenses, Crawley and Corbet deployed the Cooke S4s, a lens package they used previously on Vox Lux and The Childhood of a Leader. “Brady and I love to explore the potential alchemy of the combination of lenses, story, landscape, film stocks, but every time we’ve gravitated back to the Cooke S4s, we just really love them. I keep an open mind as to what lenses we’re going to shoot on, but we do gravitate back to them. They’re just beautiful.”

Other cameras on set included the Arricam LT, Arricam ST and Arriflex 235, with Crawley also shooting on DigiBeta for the film’s 1980s-set epilogue. “Brady initially had this idea. He wanted the aesthetic to have both an archival and patchwork quality to it. I think it’s tricky when a director says, ‘Oh, I’d like it to have a patchwork quality’ because cinematographers tend to strive for consistency of the aesthetic. You’re not trying to do something that’s pulling the audience out.”

With The Brutalist shot on location in Budapest, which doubled for New York and Philadelphia, Crawley praises the aesthetic ambitions of Corbet, who had already seen the production delayed several times, due to COVID and other issues. He cites the scene where Van Buren is accused by László’s wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) of an atrocious act. “It all just plays out in one very ambitious Steadicam shot that barely fits on a roll of film. There is no other coverage that exists of that scene. It all takes place in one shot. That’s how he likes to work.”

“It’s all one take. It’s an entire magazine of film,” confirms Corbet, who felt for Felicity Jones to perform such an emotionally complex scene on what was just her second day on set. “I felt terrible, because there was no other place I could put it in the schedule for various reasons. And I was like, ‘I’m so sorry, but we’re just going to be beating the hell out of you all day long for the next ten hours.’ And she was so unbelievably professional and prepared, and she didn’t miss a beat. And in fact, what was so crazy about this incredibly dynamic and complicated shot with so much complex choreography and so much dialogue and so many things in a row that needed to go right to achieve the shot…we actually had six perfect takes. I couldn’t figure out which one to include.”

Steady or not

Operating the Steadicam was Attila Pfeffer, who pulled off a minor miracle in the scene, says Crawley. “Brady said, ‘Okay, what I want is to have this long five-minute Steadicam shot that halfway through turns into a handheld shot and then becomes a Steadicam shot again.’ The handheld moment being where Joe Alwyn [who plays Van Buren’s son] rips Erzsébet’s walker from her, throws it across the room, and then physically drags her away from the dinner party, and towards the door, and then it rights itself and becomes Steadicam.”

Crawley praises Pfeffer’s dexterity. “I’d never witnessed anything quite like it, but he took the Steadicam and then operated it in a handheld fashion, and then righted it, and then brought it back to Steadicam again. It was really magnificent.” The scene was also complex for other reasons, not least because it moves in and out of rooms. It was also touch and go whether the camera reel would have enough film to capture such long takes. “We had our hearts in our mouths, because every single take we were just so fearful that the film was going to run out.”

Corbet also was keen to use as much handheld camerawork as possible. Take the film’s establishing scenes, where László is first glimpsed on a ship bound for New York. “That was all handheld shots until we reveal the Statue of Liberty, tumbling upside down,” says Crawley. “That was all one shot in a ship, going from the bowels up through…and I was literally operating and pulling myself up with one hand, up these very steep steps within the ship.”

Artistic touch

When it came to illuminating the scenes, Crawley wanted to avoid artificial lights where possible. “I definitely am a cinematographer that gets inspired by a certain naturalism to the lighting,” he says. “I like to do a lot of light studies in the spaces. I find that certainly with Brady, we’re often drawn to locations based on how the light is falling…and so I’m trying to often protect that as much as possible as well. I liked the idea of lighting being informed by the accidental, in a sense, or the environmental…like light skipping off water, or light skipping off cars and things like that.”

Inspired by painters ranging from Edward Hopper to Otto Dix, Crawley admits that some moments were the result of good fortune rather than rigorous planning. For example, the scene where Van Buren finds László shoveling coal. “There’s this one wide shot that we did, and I think it might be because of the negative feel of the coal on the ground or something, but it has a wonderful painterly quality. And it’s Van Buren [wearing this] orange camel coat, contrasting with the coal. And Adrien is atop this coal mine; it’s so striking and arresting. And in some ways, I have no idea how we achieved it.”

As the film moved into postproduction, Crawley reports that the production deployed push processing, the developing technique that sees stock kept in chemicals for longer. “Brady and I are continually trying to break down the stock in some way, by under exposing it and then dragging it back up and things like that. We’re almost trying to abuse it and make it less perfect. I think that does owe a debt to [then late 19th Century photography movement] Pictorialism and things like that. It was really successful on this movie. I think we got to a really beautiful point where things felt of a time and archival in some way, aesthetically.”

The colour grading took place in Budapest, with Corbet turning to the film’s dailies colourist Máté Ternyik. “About a third of the way through,” remembers Crawley, “Brady turned to me and said, ‘Why don’t we just use Máté for the final colour?’ Because he understood it so well, and he was so wonderfully involved and accommodating. And we would have great sessions at the end of a shooting day. We might go in at 11 o’clock at night and really look at the dailies. He ended up colour timing the film. And, yeah, he’s wonderful.”

Since then, The Brutalist’s journey has been a beautiful one, being rapturously received at the Venice Film Festival in September, and since winning three Golden Globes including Best Picture. With the film almost certain to be in the Academy Awards conversation this year, Crawley seems delighted that Corbet’s ambition is being recognised. “The great thing with this film and the response that it’s had…if I may say this, I feel like it’s been inspiring to audiences and to filmmakers.” And as Corbet puts it, people getting excited to see a 215-minute film about an architect: “That’s a really good thing for the movie industry.”