And so it is that a cautionary tale about unchecked chain reactions continues to spark chain reactions of its own – as one author friend observed – as nominations for Oppenheimer alight from one set of awards to another, all the way to the current baker’s dozen the film enjoys on both the BAFTA and Oscar sides of the pond. And, of course, the atomic biopic has already scored wins at the Golden Globes (about which, more momentarily).

Of course, Killers of the Flower Moon and Poor Things are right behind in the nominations tally, and so is Barbie, with eight, though the sharp-edged, pink-hued summer blockbuster seems to have lost award momentum, despite its box office dominance, as things look much more “heimer” than “Barben”, after that one brief summer moment where the two equally shared the limelight.

As for the cinematography categories, the Oscars lineup comported with the ASC’s, both including the welcome, semi-surprise of Ed Lachman ASC’s B&W work on the Chilean-set, Netflix- released dictator-as-vampire fantasy El Conde.

The one variance in the Oscars lensing lineup (featuring Hoyte van Hoytema ASC FSF NSC’s work in Oppenheimer, Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC for Killers of the Flower Moon [and not competing against himself for Barbie] Matthew Libatique ASC LPS for Maestro, and Robbie Ryan BSC ISC for the momentum-gathering Poor Things) is that the BAFTA gave their El Conde slot to another study on the effects of fascism: Polish DP (and previous Oscar nominee) Łukasz Żal PSC for Zone of Interest.

The morning of the announcements, Libatique emailed out a statement, saying it was “an honour that will never get old”, as this marks his third Academy go-round, having previously been nominated for Black Swan, and his earlier collaboration with director Bradley Cooper, A Star Is Born. “Thank you to all my fellow cinematographers in the Academy for bestowing this high honour,” he said, also thanking “the intrepid crew of Maestro” and Cooper, “for bringing me aboard this beautiful journey”.

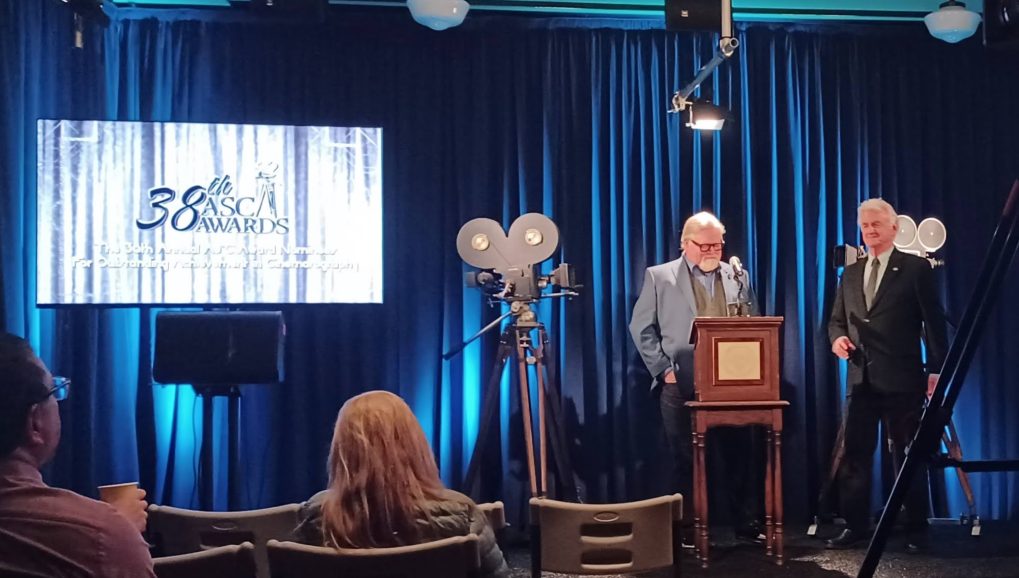

Another part of that journey, at least for DPs, begins with the ASC nominations, ahead of the Oscars (like pretty much everything else, leaving the Academy to put a bow on the whole season). Those nominations begin, in turn, with a convivial weekday brunch at the ASC Clubhouse, where they are announced – by society president Shelly Johnson ASC, and awards committee chairman Chuck Minsky ASC. One new category this year was for music videos (sponsored by Unreal Engine – each of the categories, in the manner of soccer team jerseys, has its own sponsor), and among the trio of nominees was Jon Joffin ASC, for Jon Bryant’s At Home, making him a double nominee, as he also wound up in the “half hour series” category for his work on Schmigadoon!, the loving spoof of all things Broadway and West End, which mysteriously wasn’t renewed by Apple TV+ (Joffin was also Emmy nominated for the same show).

Every vote counts

Though nominations alone can be life-changing, of course. DP Jerry Henry had one in Emmy’s nonfiction cinematography category, for The 1619 Project, which looks at the history of slavery in America, the role it played in the country’s founding, and the pernicious, lingering effects that now-vanquished institution still has.

Henry didn’t win, but wrote later, saying “when I found out I was nominated for an Emmy, the gravity of the importance really hit me once I arrived with my family at the award ceremony. My wife and kids turned to me and told me how incredibly proud of me they were. It’s an honour to be recognised for your work after hustling and grinding for 27 years. I put 100% of my heart and soul into The 1619 Project and I love what I was able to contribute visually. The ceremony was epic. We won Outstanding Documentary Series, and I can say I have made the ancestors proud!”

That ceremony would be the second night of the Creative Arts Emmys, which fall the weekend before the “regular” Emmys of best drama and comedy fame, which themselves are broadcast on TV. That same second night coincided with the Golden Globes, but the first Creative Arts evening featured the three winners for cinematography in narrative categories; M. David Mullen ASC for the concluding installment of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Christian Sprenger ASC, for his work on Atlanta, and Natalie Kingston, for the “Hand to Mouth” episode of Apple TV+’s prison-set Black Bird.

Both Mullen and Sprenger were repeat winners. Mullen profusely thanked everyone for “these crazy five seasons,” from series creator Amy Sherman-Palladino and her executive producer husband Daniel, on down to every member of his camera crew, including the Steadicam operators that made the episode’s elaborate tracking shots possible.

Sprenger mentioned that Atlanta had developed “a style and aesthetic” early on, and since there were “very few directors on the show,” it was easy to maintain. And yet, in using “different lenses that we’d normally use”, the winning, LF-formatted episode gave them an “excuse to make some new decisions”.

The newest decision of all, though, came with the Academy giving Kingston an award in the Limited or Anthology Series or Movie category, making her the first woman to ever win a cinematography Emmy for narrative work. “I hope this inspires many other women and non-binary cinematographers to keep grinding at their crafts and to know that this is possible,” she said in a later email. “I hope this is one step closer to dropping the word ‘female’ in front of the ’cinematographer’.”

As for other trends involving the word “female”, it appears Poor Things has now picked up the “comic feminist lens” mantle for overdue critiques of clearly not-quite-working social arrangements. Or at least the ones now likely to haul in awards. Though yes, that film was written and directed by a dude, Yorgos Lanthimos, who also finds himself as a “best director” finalist, while Barbie’s DGA-nominated director, Greta Gerwig, does not. (The AP has a good overview of Oscar snubs and surprises.)

Indeed, some of that momentum, or lack thereof, was evident on Globes’ night, where Barbie won what was, essentially, a new “best box office” category there, but Emma Stone won an acting prize for her riff on Frankenstein’s monster, while Poor Things won in the comedy/musical category, leaving it, seemingly, as one of Oppenheimer’s few remaining award competitors.

Though on Globes night, not everything was such a weighty consideration. To wit:

“We were all in the Calvin Klein ad.”

As a statement of solidarity, it may not have quite the ring of “Ich bin ein Berliner,” or even “I am Spartacus,” if we’re sticking to Hollywood fare, but it was precisely the kind of unlikely utterance that the Globes –with its own particular tipsy, unrestrained history – has become famous for. Or infamous.

Though the Globes’ more recent infamy has included scandals relating to how small and non-diverse its voting base was, especially given its outsize, early January influence in shaping award season perceptions, and those subsequent reactions.

This was also the first fully revived Globes show of the semi-post pandemic era (and along with the delayed Emmys, the first big “post-strike” award show, to boot).

And while the Globes’ broadcast was generally lambasted for a certain flatness, and its quickly derailing attempts at humour, one advantage of watching from the media room is that you are generally spared most of those aspects, especially once the recipients come back for their Q&As.

But members of the fourth estate aren’t immune from their own attempts at trying to make things meme-or-viral worthy, and so came the questions to Jeremy Allen White, after The Bear’s wins on the TV side, about how he felt when most of the red carpet buzz that evening was over his recently unveiled Calvin Klein ad, instead of his acting work. “It is strange,” he allowed. “It’s been a weird couple of days.” Which led to a follow up – from a renowned British tabloid, no less! – to the whole cast, about whether said buzz would make them want to get into better, more Calvin-like, shape.

At which point they all immediately became protective of one another, saying any and all of the body shapes represented by the actors were just fine in their own right, thank you very much, and White was just being himself in the advert, standing in, really, for all of them. Hence “we were all in that Calvin ad.”

But the questions weren’t all just froth, like the inexorably flattening bubbles in the backstage champagne, somehow also made available to the press. Director Christopher Nolan came in with his Oppenheimer cast members and fielded a question from a colleague whose uncle had worked with Oppenheimer, asking whether the scientist remained perpetually haunted after having successfully turned split atoms into weapons of mass horror, as per the film’s very last scene.

“That’s a heavy question for a backstage interview,” Nolan said. And while Oppenheimer “always maintained his loyalty to his country,” he also agreed that his actions generally showed the scientist was “racked with guilt.” Cillian Murphy described the figure he portrayed as “complex and contradictory and brilliant and arrogant and vain.”

Paul Giamatti had been there ahead of them, after his win for playing the overwintering teacher in The Holdovers (a best picture nominee whose director, Alexander Payne, was, like Gerwig, left out of the directing category).

We asked him to follow up on an earlier surprise answer on the red carpet, about an abiding fondness for horror films, saying he’d loved them “since I was a little kid.” Movies in general “go deep” at that age, and horror films go deeper still, he said, remarking on an even more surprising love for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, adding “I don’t know if I would be a chainsaw killer, I don’t know, but I just love them, they are great. You can get away with a lot.”

Rowing to victory

Of course, it was something far more horrific than one loose chainsaw killer in Texas that haunted Oppenheimer himself, and post-Globes, that film’s “strong force” hold on awards season continued to be borne out by the regional and national film critic groups who also get handsy with accolades during this calendar stretch. One such group, the Phoenix Film Critics Association, also has a category for “overlooked film of the year”.

Films such as the Judy Blume adaptation Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret leap to mind, as does the roots-of-modern-wrestling-and-harrowing-family-tragedy of The Iron Claw. The PFCA’s own winner in this category was the George Clooney-directed The Boys in the Boat, the story of the 1936 University of Washington rowing team, which against all odds rowed its way past US private colleges for a national rowing championship (the UW is a public institution), and into that year’s Olympics, where they beat host Germany’s team, at those infamous, Nazi-infected games (Jesse Owens even makes a cameo appearance).

One might imagine that conclusion alone would make the story attractive to a director like Clooney, but in interviews, he’s also talked about being drawn to the docudrama’s theme of a disparate working class team (at least, economically disparate – public universities in America were once much more accessible to the actual public), coming together in egalitarian fashion, achieving a common and uplifting purpose, and setting the bad guys on their heels a bit, to boot.

Shooting that historical opus was Clooney’s longstanding cinematographic collaborator, Martin Ruhe ASC. When we last talked to him, around the time of the also-Amazon-released The Tender Bar, he told us he was off to England to start prepping for Boat. Indeed, the UK stands in for everything, particularly passing well for the Hudson River Valley, where a key race was held (even if not quite fully emulating America’s Pacific coast).

“We had five big races,” in the original script, Ruhe told us, but “in the end we shot four.” What was surprising was the complexity in capturing those races. Or perhaps not, considering the dynamism and tension in those scenes, and that they took place on constantly moving water.

Although Ruhe is quick to credit visual effects – someone had to take out any straying overhead jets when they were shooting under a flight path near Windsor Castle, after all – nearly as much as the planning and prep that went into shooting. There was a small, catamaran-like camera boat, along with “a bigger boat with a jib arm and Ronin,” which could only carry a small camera. On some boats, the camera replaced the coxswain for some shots, while a larger craft also boasting a Supertechno crane was constructed too, but which created a bigger wake, affecting the rowing of the actors (and of the actual rowing crews around them in the other boats).

There was also a drone with an Alexa Mini, but most of the action was captured with Sony Venice cameras sporting ARRI Alpha lenses. “I wanted to use the Rialto system,” Ruhe says, understandably wanting “the flexibility”, but at that time, the Venice 2 “didn’t have (it) yet”.

In those pre-TV days, rowing “was the most watched sport in the whole of the US – hundreds of thousands people along the shore,” would come to look at races. It was so pre-TV, that it became a bit of a challenge to find visual source material. One of the most helpful, as it turned out, was the infamous Leni Riefenstahl propaganda-laden documentary of that same event, Olympia. The rowing sequences in it had “the highest intensity we could see in any footage”, with cameras not only on shore, but in the boat as well, “moving in, moving out”. Indeed, the sport is “very repetitive – you move all the time, it’s hard to get a good close-up”.

But Boys in the Boat gets many of them. It’s interesting then that what was a cause for national celebration when it happened in 1936 – an event that most of the country, beyond those hundred of thousands on the banks, either listened to on radio or read about in newspapers – now, as a filmed story, competes for attention in an overwhelmingly visual age.

Perhaps even like Oscar broadcasts do now, which no longer boast those same levels of viewership they had when they were perceived as a national event, and when there were only three networks. Whether a widespread critical hit like Oppenheimer can bring viewers back to watch the film get lauded, in an age where audiences, opinions, and attention are all split like atoms, remains to be seen.

And we will see you back here in a month, as more verdicts from the award circuit are in.