COURTING RIVALS

Thai cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom serves up a winning shot with 35mm Kodak film, precise aspect ratios, and innovative techniques in Challengers.

In their electrifyingly propulsive Challengers, director Luca Guadagnino and cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom set out not to make a conventional “tennis film” but rather an erotically charged drama, set in the world of professional tennis, that would depict the high-speed kinetics of desire between three long-time rivals locked in a passionate love triangle on and off the court.

Tashi Duncan (Zendaya) is a tennis star on the rise, her talent and drive fuelled by a personal intensity the likes of which contemporaries, including Art Donaldson (Mike Faist) and Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor) have never seen. Best friends and competitive rivals, both set out to seduce her. Framed by a “challengers” tennis match that takes place 13 years after Art and Patrick first met Tashi, the film volleys between time periods; as Tashi suffers an injury that alters her trajectory, as Art and Tashi marry and have a daughter, as Patrick forces them to question everything, Guadagnino’s film is driven forward by the throbbing, furious rhythms of their ménage-a-trois.

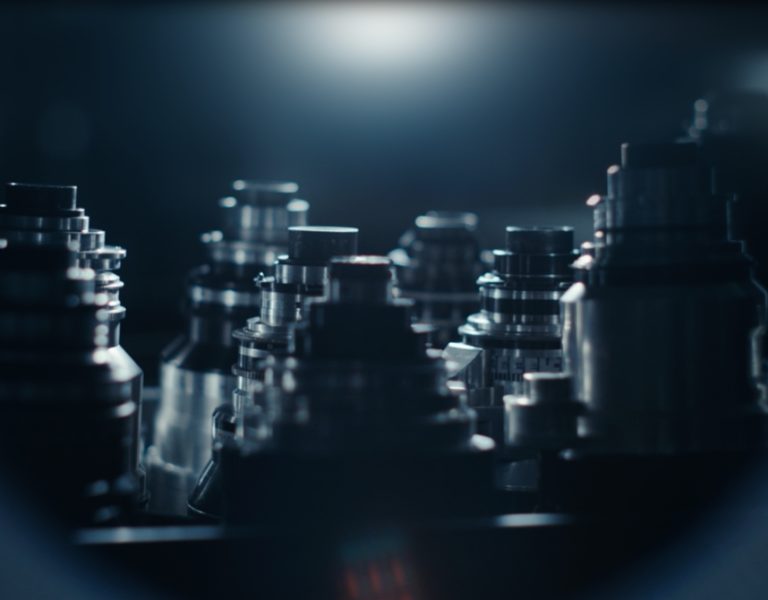

Shooting on Kodak 35mm film, Mukdeeprom framed Challengers in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, using ArriCam LT and ST cameras with Zeiss Super Speed lenses that gave him more control over low or available light situations; for the cinematographer, communicating a sense of emotional reality, even in the vivid environ of professional tennis, was paramount. As on Call Me by Your Name and Suspiria – two previous collaborations with Guadagnino – Mukdeeprom opted for 35mm Kodak Vision3 5219 500T filmstock, capturing in 3-perf for the entire production.

“I always use Kodak Vision3 5219 500T, for everything,” he says. “I’ve found that it has superior grain structure, for digital intermediate (DI).” Its texture and sensitivity gave Mukdeeprom the versatility to handle a wide range of lighting conditions, from sunny to darkened interiors, and the Kodak emulsion offered additional range for capturing skin tones, another important consideration in the visual language of Challengers.

“For film in general, I found that there is hidden information in between digital steps, especially in the lower range/dark area,” Mukdeeprom adds. “My theory is that the variety in the size of chemical particles on film has a lot to do with this, but that’s just my theory.”

Natural and vintage lighting

In lighting Challengers using standard ARRI HMIs and Tungsten fixtures, in combination with Creamsource Vortex8 fixtures and DMG line LEDs, the filmmaking team took advantage of available daylight to light scenes, augmenting it where necessary by bouncing soft light into the sets. “I want it to be real,” Mukdeeprom explains. “I don’t want to feel that we use LEDs everywhere. I want to feel the reality of a light bulb or source that is from that era.”

Guadagnino always presents his cinematographers with unique challenges. On Call Me by Your Name, he instructed Mukdeeprom to use only one 35mm lens to sustain the film’s intimate naturalism, and Suspiria involved a great deal of focal lengths and frame rates, also toggling between zooms and push-ins to achieve distinct dramatic effects that suited his bleak, baroque reimagining of Dario Argento’s giallo.

Ball’s eye view

As Challengers escalates, the audience learns enough about its characters to understand all that’s in play during a climactic match. Guadagnino unleashes one impossible shot after another in this finale: first-person-perspective shots of the ball speeding from racquet to racquet, a faux-double split-diopter composite shot of all three players, a moment where the players are filmed from below the court, moving across its surface like figures in an Italian Renaissance fresco.

Mukdeeprom first set out to capture a shot from the tennis ball’s point of view, spinning as it’s propelled across the court, without visual effects, but none of the preproduction tests—including one in which the dolly crew sprinted as fast as possible to simulate the ball in motion—conveyed the elevated naturalism that he and Guadagnino were after. For the under-court shot, however, Mukdeeprom devises a transparent platform for the actors to stand on, placing the camera beneath it and positioning a horizon line to help orient viewers.

Late in the game, Challengers is dominated by stylised close-ups, including a long full-court zoom onto Zendaya’s face in the stands, staring impassively forward as spectators around her swivel left and right to follow the gameplay (a direct homage to Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train), as well as a shallow-focus shot of Mike Faist towering over the camera, sweat drops landing on the lens.

To capture the actors at 2,000 frames a second for these standout shots, used to thrilling effect to convey the complexity of competitive tensions within and between the three leads during a three-set tennis match Guadagnino flew in a vintage film camera from Italy, to shoot in slow-motion. Mukdeeprom shot 1,000-foot rolls.

“To use a film camera for this was about the beauty of it, rather than necessity,” Mukdeeprom says. “Of course, we can — and it is a lot easier to — use high-speed digital, and I can assure that it is going to work very well, also. But Luca kept this idea.”

Mukdeeprom concedes it was “quite complicated for him” in the beginning, “but frankly” Guadagnino dictated his decisions. “I trust him to know what we are going to do,” he adds. “We’ve worked together for quite some time, so I know I can trust him, like you trust a friend or your family.”