Enigma Variations

Oscar Faura / The Imitation Game

Enigma Variations

Oscar Faura / The Imitation Game

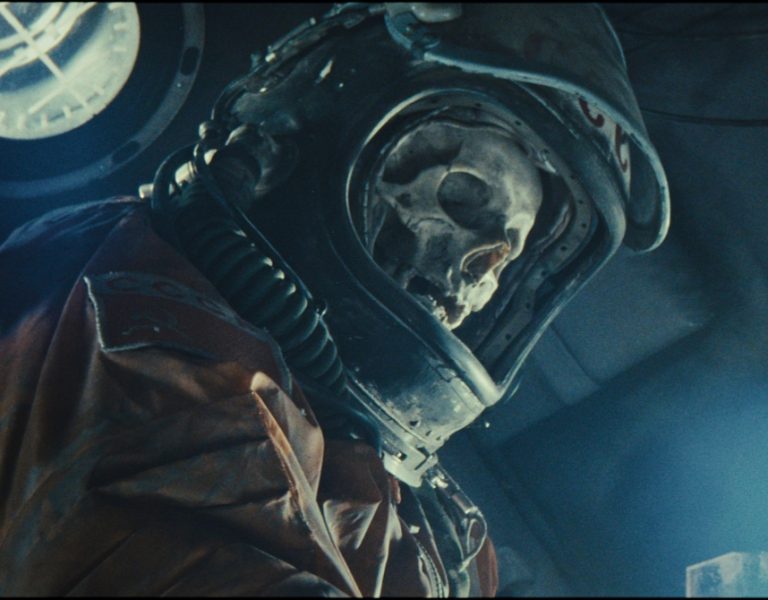

The Imitation Game is the highly-praised, British-American historical thriller about British mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst and pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing. A key figure in cracking Nazi Germany's Enigma code, that helped the Allies to win World War II, Turing was later criminally prosecuted for his homosexuality.

Based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges, the movie stars Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing, was helmed by Norwegian director Morten Tyldum, making his English-language directorial debut, with a screenplay by Graham Moore. It was lensed on film by Spanish cinematographer Óscar Faura, whose credits include The Orphanage (2007) and The Impossible (2012).

The film spans key periods in Turing's life: his unhappy teenage years at boarding school; the triumph of his secret wartime work on the revolutionary electro-mechanical bombe that was capable of breaking 3,000 Enigma-generated naval codes a day; and the tragedy of his post-war decline, stemming from his admission of maintaining a homosexual relationship and his conviction for gross indecency.

After a bidding process against five other studios, The Weinstein Company acquired the movie for a record $7 million in February 2014, the highest ever amount paid for US distribution rights at the European Film Market.

Principal celluloid photography began on 15 September 2013 in England. Filming locations included Turing's former school, Sherborne, Bletchley Park where he and his colleagues worked during the war, Nettlebed in Oxfordshire, and Chesham in Buckinghamshire. Scenes were also filmed at Bicester Airfield and outside the Law Society Building in Chancery Lane. Principal photography finished on 11 November 2013.

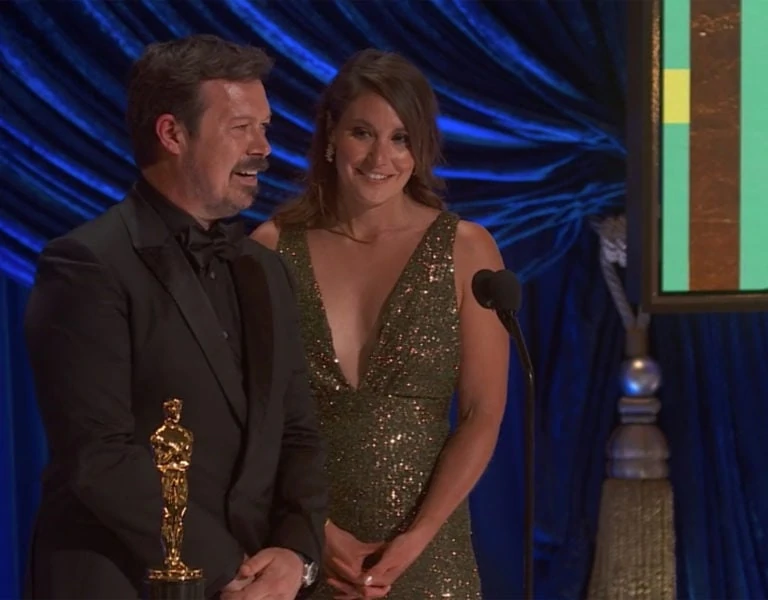

The Imitation Game has garnered praise from critics, following screenings at festivals worldwide. The New York Post’s Lou Lumenick described it as a "thoroughly engrossing Oscar-calibre movie", whilst Empire called it a "superb thriller". Praise has also been given to Keira Knightley's supporting performance as Joan Clarke, William Goldenberg's editing, Alexandre Desplat's score, Maria Djurkovic's production design and Faura's cinematography.

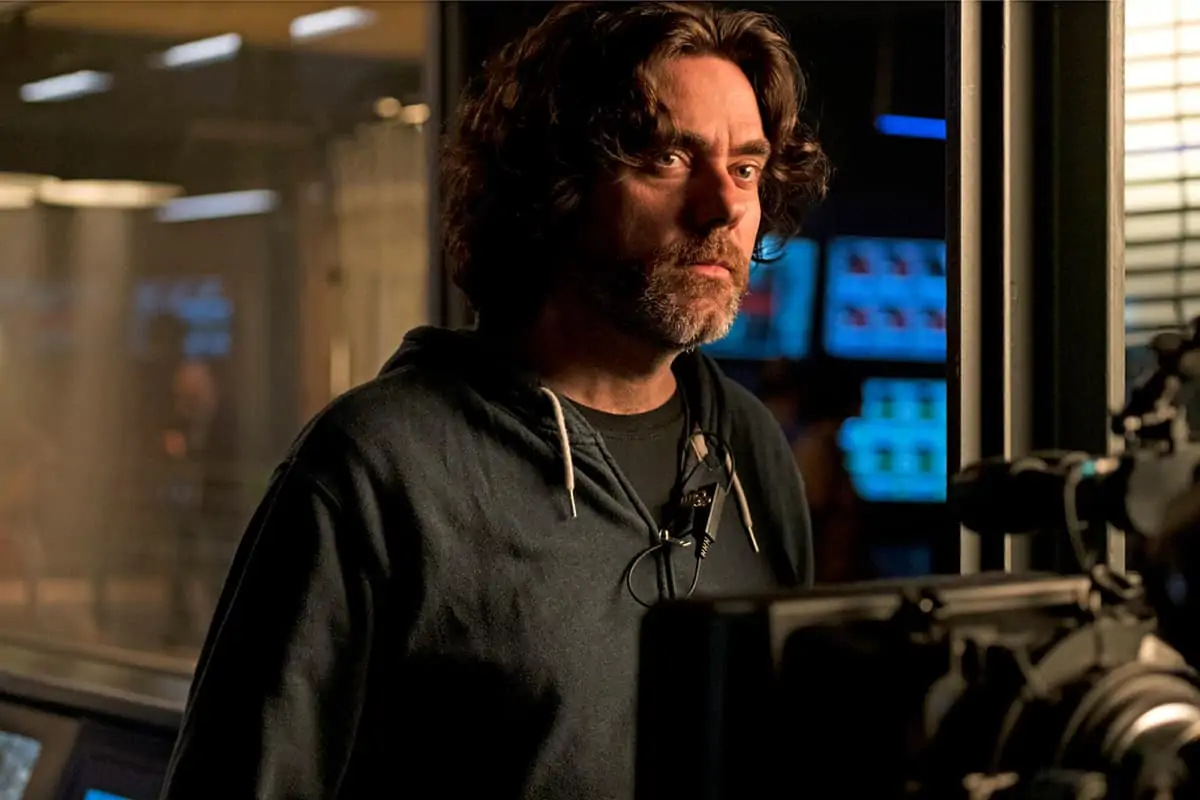

How did you come to get involved with The Imitation Game?

OF: Morten Tyldum called me. He knew my previous work and asked me to shoot the movie. He mentioned the photography on one of my earlier films, The Impossible, a story about the 2012 Thailand tsunami, in our first conversation, and was looking for that sort of realistic look for The Imitation Game.

What appealed to you about The Imitation Game?

OF: First of all, the script. It was terrific – a great story, masterfully written. I thought it would be amazing to contribute to tell the story of Alan Turing, one of the most important figures of the twentieth century. I also loved the idea of shooting a period movie for the first time.

How did you and the director envisage the film?

OF: From the beginning of the project, Morten and I agreed that the film should look realistic, but visually appealing. We were telling an historic event and we wanted to be accurate without being harsh. Our goal was to achieve a certain visual tone that would contribute to tell the story not just being flat. It was a delicate balance because we also didn’t want the movie to look stylised. The movie jumps back and forth between different moments Turing’s life. Our goal was to give those time periods – the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s – distinctive looks. For the 1930s, when we learn about young Alan’s story, we tried to achieve an overall bright and clean ambience, appealing to the innocence of his school days. We decided to avoid the clichéd colour palette of some World War II movies for the 1940’s scenes, instead using rich colours in costumes and in some elements of the sets. We wanted the 1950’s police investigation plot to look gray, rainy and sad.

What research did you do?

OF: Obviously we started our research with the historical documentation. We watched different movies where we found pieces that helped us to find the look of the movie. In my opinion, even if you don’t find a clear reference to follow, it’s always a very interesting exercise to do, because you can exchange ideas and visions about how the movie should look. It’s a dialogue starter.

How much time did you have for prep/pre-production, and what was the working schedule?

OF: I had six preparation weeks and we shot the movie in eight weeks. We did five six-day and three five-day weeks. It was hard to accomplish but we did it.

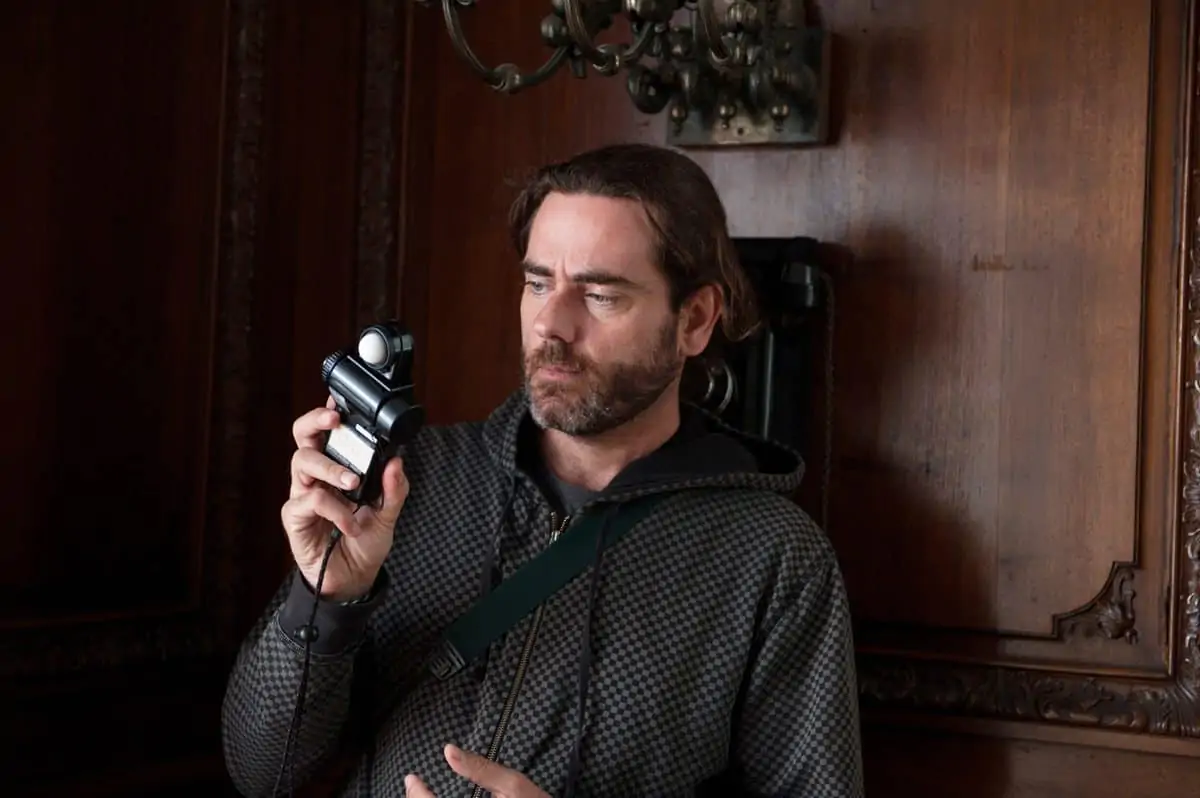

What cameras, formats and aspect ratio did you select?

OF: We decided to go 3-perf, Super 35mm with spherical lenses, with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. We had two cameras – an Arricam ST and Arricam LT. We used them together for the dialogue scenes. Our lenses were the ARRI Master Primes. I love Master Primes because of their superb quality and their shallow depth-of-field. I chose them too because of their high speed, very useful at night scenes. We didn’t use any special filters, just neutral density to control the depth-of-field. The camera equipment came from Take 2 and lights and grip came from ARRI Rental.

Why did you select film and not digital?

OF: Morten and I agreed that that film was the correct option for The Imitation Game. Digital was not an option, because we wanted to keep the texture of the negative that has been used for years to shoot most World War II movies. In my opinion, the audience does a visual association when they watch that kind of movie. It is something that unconsciously makes them relate a historic period to a certain kind of image.

Which filmstocks did you choose?

OF: I chose Kodak Vision3 5219 500T and 5207 250D. The 500T was used for night scenes, as well as day scenes shot in the studio. All the scenes at Hut 8, which was built on a stage and was where the cryptologists worked together, were shot with 500T and lit with tungsten. I used the 250D for day exteriors, day interior locations at Hut 11, where they built the machine, and the police office in Manchester. The scenes set in the 1950s also were shot mostly with the 250D negative. The film was processed at i-Dailies in London. Every day I received a hard drive with the scanned dailies from the previous workday, and I viewed them on my computer.

"We started our research with the historical documentation. We watched different movies where we found pieces that helped us to find the look of the movie."

- Oscar Fauna

Who were your crew?

OF: I brought my usual camera operator from Spain, Albert Carreras. We have worked together for many years and he is my right hand on set. My gaffer was Stuart King, Tim Battersby was the focus puller and Gary Hutchkins was the dolly grip. The Steadicam operator was Peter Wignall. All of my crew did an incredible work. I couldn’t be more satisfied.

What was your approach to the camera movement?

OF: We combined dolly or handheld depending on the dramatic intensity of the scene. We chose the Fischer 11 as our dolly for its stability and smoothness. We tried to reserve the camera movement for specific moments of the story to get a more emphatic result. We did some Steadicam shots in situations where it was impossible to set the dolly and the handheld was not adequate. There are three scenes in the final cut that were shot using Steadicam. One was shot in a cloister at Sherborne School following young Alan Turing after being beaten. We used the Steadicam for a long shot at the Manchester Police office and at Kings Cross train station during the kid’s evacuation scene.

And was your approach to the lighting? And what lights did you use?

OF: My idea was to create a natural atmosphere, trying to respect the actual light sources of the different locations. I worked alongside Maria Djurkovic, the production designer, on the distribution of the different kind of practical lights. Fluorescents, anglepoises and hanging lamps were distributed to get different light ambient.

What were your main concerns during the shoot?

OF: My biggest concern was the lighting for the night exteriors because of the wartime blackout. During the WWII, after dark no light was permitted to avoid giving the German bombers any visual reference. Windows were blacked out, cars drove with snoots on their headlights and streetlights were off. That means that the options in terms of lighting to solve the night scenes were limited.

Were there any happy accidents, unexpected things that worked out well?

OF: I consider we were lucky with the weather. We never had to stop shooting because of the rain, and we had sun in the two scenes we requested it: the picnic at Blechtley Park and young Alan Turing talking with Christopher by the tree in Sherborne.

Where did you do the DI?

OF: I did the DI with Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company3 in L.A. I’m really satisfied with the result. For me the colour grading is the process in which everything, that is already set but hidden in the exposed negative, gets its correct place. It’s like being a sculptor, removing what’s not necessary to get the final shape.