Home » Features » Opinion » Across The Pond »

With Cine Gear around the corner, our LA columnist examines the possible implications of the writers’ strike on the much anticipated tradeshow, and speaks to DPs Checco Varese ASC and Ludovica Isidori about their latest projects.

As this column goes up, we’ll be on the eve of Cine Gear here in Los Angeles, and its return to the Paramount lot, for the first time in the new era (if we’re using COVID to mark the closing of last one, and the thawing of its restrictions as the start of another).

But like everything else here in Los Angeles, and in “Hollywood” in its broadest, global sense, there’s no escaping the implications of the ongoing writers’ strike (and the swirling speculation about whether scribes will eventually be joined by actors, and directors – or not).

They’re so pervasive, that each of the two DPs we’re spotlighting in this edition – one, an Emmy winner talking about his latest series, the other, a rising indie star speaking about her current feature – were adamant that their thoughts about the current labour struggle, and its larger, perhaps even existential meaning, be clearly attributed to them.

No shirking as the storm unfolds, for either of them.

Even Cine Gear felt obliged to weigh in. While the show has stressed, in a note to exhibitors, that it “supports the Writers Guild of America’s fight for better work conditions, (it is) equally important to know that Cine Gear Expo is not a ‘struck’ event and the picketing you may encounter stems from a labour dispute between the WGA and Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) of which Paramount is a member.

“Cine Gear staff and other assistance will be available at all respective gates to assure smooth traffic flow of vehicles and pedestrians and are committed to ensuring a successful and enriching experience for all.”

Which may make things interesting if all those camera and other crew folk – both accomplished and aspiring – there to scout out the latest tools of trade, are perceived, somehow, as “crossing” picket lines, even though none, of course, will be there to work on productions. Though there will undoubtedly be an even more fervent level of networking in the search for any production that can offer a “locked” script, and still go ahead and shoot.

One assumes that the Teamsters – who have been surprisingly adamant about not having their trucks cross picket lines either – will still bring all the exhibition equipment onto the lot. But that we’re even asking the question at all shows how this Hollywood shutdown continues to become unprecedented in consistently new ways.

RETRO FLAIR

As for locked scripts, well, Checco Varese ASC has started shooting one in South Africa. And that’s where he was when we caught up with him over Zoom, about his most recent show, Amazon’s Daisy Jones & the Six.

It’s the kind of show, with its L.A. rock ‘n’ roll-in-the-‘70s backdrop, and strong critical praise, that would seem a likely Emmy contender. And while there will certainly be Emmy nominees this year, will there be an actual Emmy awards ceremony?

With each passing week, the question lingers in the air a little longer, though what ultimately was agreed-upon for June’s Tony Awards broadcast may serve as a template, should the walkout go that long: “WGA has agreed not to picket the broadcast, which will consist of non-scripted segments. What does this likely mean for the broadcast? You’ll likely see performances from nominated shows, an in-memoriam segment, but not host-led banter or elaborate opening numbers.”

But of course, the Tonys are there to promote non-WGA work, and non-studio shows, on live stages. The Emmy calculus could be quite different.

Varese, meanwhile, notes his film has proceeded with “the caveat that you cannot change anything in the script”. They are currently also locking down locations for the Viola Davis project, and he acknowledges, “We are a few of the lucky ones.”

Continuing about the strike, he adds “it’s hard to not be in solidarity with the working class, blue collar, or typewriter class,” wondering why, when companies crow that “we made two billion dollars […] and then all of a sudden you say ‘why don’t we get a raise?’, [they respond] ‘oh no, it’s bad for the shareholders.’ ‘The shareholders’ are an entity that’s being created – ‘shareholders’ are a concept.” Certainly, in contrast, it would seem, to the people making the “product” in question. He continues: “That’s where I find myself torn between yes I need to work” and the idea of honouring picket lines wherever they may be.

Adding that his grandfather was also a union member, as, of course, is he, he jokes that for Cine Gear “they’ll have to make a door for [the show] and a door for people going to work,” at least to get the picketing sorted.

As for his recreating a very specific era for Daisy Jones, and its distillation, as it played out along California’s Pacific cusp, he used a Sony Venice – the first version – along “with Optimo Primes and Optimo zooms.”

The flares that set-up gave him, he found, were “very beautiful – all these flares that I would have embraced” had he been photographing at the time, as Varese also goes on to note that his preference for historical research runs toward still photographs, more than period films.

To get his period look, they “did a very extensive test” with 17 sets’ worth of glass, from Keslow, before arriving on the Optimos.

There were also the films-within-the-film, such as the framing the story in terms of a ‘90s-era documentary, flashing back to The Six’s heyday, before their tumultuous, Fleetwood Mac-like ascendancy and breakup.

And within the story, one of the characters, Camila Dunne, wife of band co-founder Billy Dunne, played by Camila Morrone (speaking of additional layers within the film), is herself a photographer, and often seen documenting the band’s rise and turmoils herself with a Super 8 camera. Morrone was “shooting (her own) pictures, she was shooting the Super 8,” Varese says, and he picked up one of the cameras bought by the production, and “did a little more”.

In addition to singing the praises of the art department, for so splendidly recreating and augmenting many of the authentic locations (such as the Sunset Strip and its clubs, and various legendary recording studios), Varese, who shot the first six of the show’s 10 episodes, started with the story’s Pittsburgh-set beginnings, where The Six (ahead of meeting Jones in L.A.) began life playing for dances and weddings.

Except that “Pittsburgh”, in this case, was a series of carefully chosen locations around L.A., including a lot of the early 20th century architecture of Echo Park. “I decided that Pittsburgh is northern light, blue light,” he said of those scenes. He also “worked very closely” with DIT Daniele Colombera to help refine that “patina of (a) colder feeling”.

Then of course they head out for the yonder coast, straight into “this myth (that when) you drive west where the sun sets, everything is warm”, which brings “a different kind of patina, of hope, and the future”. Though he did enough research into the era, and its leaded smog, to realise that “in the ‘70s the sky was probably brown.”

But while they gave everything “this patina of age”, as well, it was all “very delicate”, both the source footage in the ‘70s, and the wrap-around documentary from the ostensible ‘90s, to lend, simultaneously, a “gravitas of being [from] a different decade or a different century” while serving the audience’s need (and in this case, Amazon’s mastering requirements), that it’s all “supposed to look better, or more modern”.

“We put a little grain of sand” in what was being shot, he says, including by the filmmakers and videographers within the story, “and we wound up creating beautiful sandcastles.”

DEPALMA’S INFLUENCE

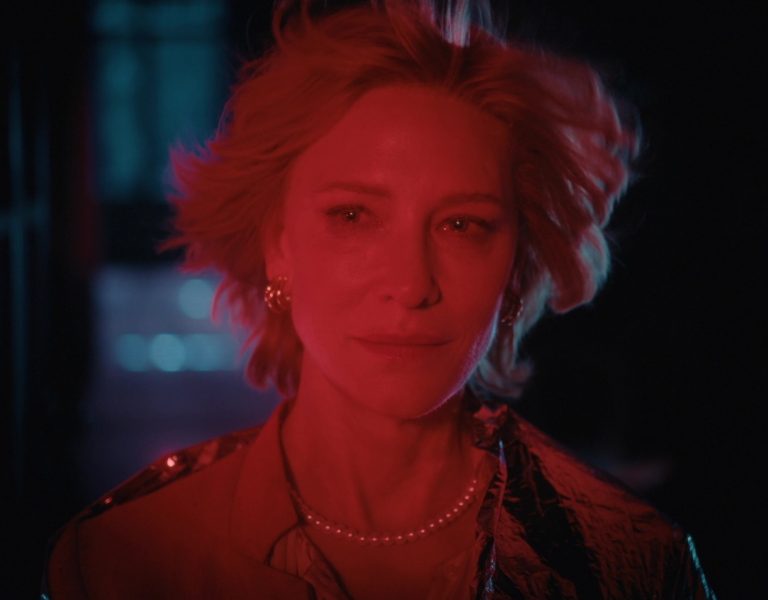

Also creating sandcastles, though in this case, constantly shifting, psychological ones, are Margaret Qualley and Catch-22’s Christopher Abbott, in the current two-hander Sanctuary. He’s a corporate heir, and she’s a dominatrix, and the film takes place during what is supposed to be their final session, before Abbott’s character, Hal, grows up and gets serious about assuming the family business.

But it’s in that whole “assumption” part that things keep going decidedly, harrowingly, and engagingly wrong.

Cinematographer Ludovica Isidori, an Italian native who’d been living in L.A., had just relocated to New York when we spoke. Though that was just many of the life changes she’d recently gone through, having been 7 ½ months pregnant when she flew to NY to meet director Zachary Wigon, who’d seen “a short movie that I made, called Willing to Go There [which] had a similar noir tone – and he loved it. So he called me. It was funny – it was the first time I had a meeting with a director,” and, she adds, it felt “like he was pitching himself to me”.

You might think part of the pitch would include references to other films built around compressed (and repressed) class-based psychological power shifts, like The Night Porter, The Servant or The Maids. But no, it turns out that they “mostly immersed ourselves in (the films of Brian) DePalma. Zach, the director, loves him.”

DePalma, known for films like Carrie, Scarface, The Untouchables, and many more, burst onto the scene concurrently with contemporaries like Spielberg, Coppola, and Scorsese, was part of a “time frame (within) cinema that’s aware of itself”.

Similarly here, while that self-awareness may not have quite the deliberateness of, say, Bertolt Brecht with his theatre audiences, “we’re not trying to create a realistic or naturalist movement. We wanted to look at camera movement, blocking – you’re aware that you’re looking at a movie, but that doesn’t distract you.” So while there aren’t split screens, or Sergei Eisenstein recreations, à la DePalma, there are a couple of times the camera is in motion in ways that definitely remind you that this is a movie, and not a window you happen to be peering through as a spectator.

Making all those camera moves was an ALEXA Mini. They’d tested the large format versions, but didn’t want the images themselves to become distracting – at least, not in unintended ways.

There was also a of “playing with focus”, starting with “Cooke anamorphics in the beginning, regular spherical Cookes [in the middle, and] for the end, we went with the Atlas anamorphics”, in a return to the “heightened” visuals of the “beginning, [where] it’s a full on play”, before the roles break down, and then, reassert themselves in brand new ways.

When the conversation inevitably pivots to film and TV workers asserting themselves over current working conditions, and the divvying up of fiduciary pies, Isidori asks “why is it that choosing an artistic career cannot be financially sustainable? We call it an industry (but) it should be more equitable.”

She also notes that “this writer strike is impacting, tragically, indie cinema. It’s asking everyone not to work. If you lose momentum making an independent movie, you might not make it ever again.” And even if you manage to make it, eventually, with “fewer independent movies coming out, (it’s) going to impact the festivals” where those films can be discovered, and many of the festivals, she points out, are still recovering from COVID.

“Independent cinema” – never mind the latest superhero instalments, or writers’ room sizes for TV, is “fighting tooth and nail to just be made”, and could be disproportionately affected. “We need to start reintegrating complexity” into how we view issues, she offers. “Discussions are good.”

But it would also seem that America is a place where fewer and fewer people have discussions with each other at all. It’s almost like they need to be film characters for that to happen.

The film she’s slated to shoot next was “supposed to go this summer”, but since it’s not, “maybe they’re going to take some time to actually prep (and) spend time seeing locations – breathe and develop. No money’s going to come anyway – maybe we can breathe intellectually and creatively.”

Normally, budgets and time are so tight – particularly on the indie end – that “you lose the ability to think on set.” And “the ability to rest is actually a form of resistance, a form of protest”, particularly, she notes, in relentlessly market-driven economies.

So when things inadvertently slow down, well, hey, “you need to see life,” Isidori says.

We’ll have seen another month’s worth of it – and Cine Gear itself – when we meet you back here next time.