Jungle VIP

Henry Braham BSC / The Legend Of Tarzan

Jungle VIP

Henry Braham BSC / The Legend Of Tarzan

BY: Ron Prince

A decade after Tarzan left Africa to live in Victorian England as John Clayton III with his wife Jane, the couple are lured back to the Congo under false pretences by Leon Rom. A treacherous envoy of King Leopold, Rom plans to entrap Tarzan and deliver him to an old enemy in exchange for diamonds. But when Jane becomes a pawn in Rom’s devious doings, Tarzan must return to the jungle to save the woman he loves.

The $180million Warner Bros. Pictures production of The Legend Of Tarzan is based on the famous fictional character originally created by Edgar Rice Burroughs. The new movie is directed by David Yates, written by Adam Cozad and Craig Brewer and stars Alexander Skarsgård as Tarzan, Margot Robbie as Jane, with Christoph Waltz portraying their double-dealing nemesis Rom.

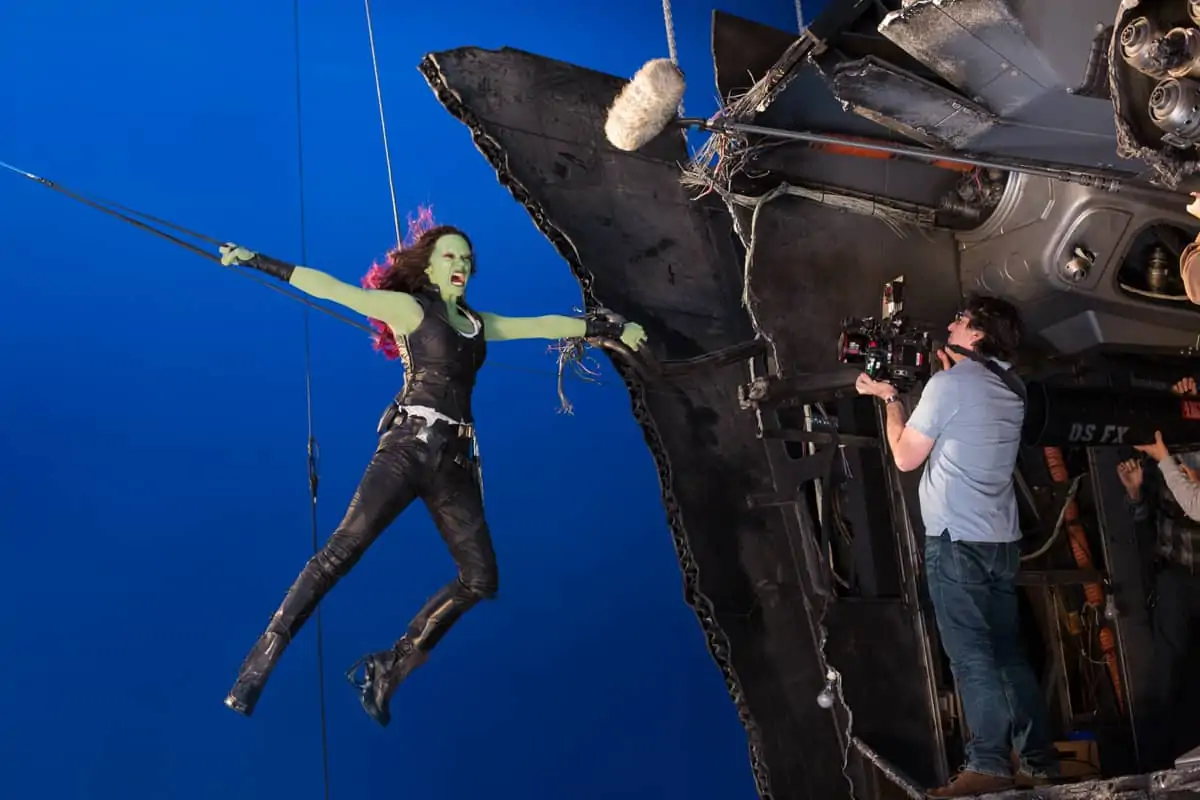

Principal photography began on June 30, 2014, at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden, under the supervision of cinematographer Henry Braham BSC, and wrapped four months later on October 3rd. Amongst the sets on the backlot was a large working waterfall and a 100-foot-long collapsible pier. Inside the studios were entire jungles with climate effects. Making Africa and its jungles appear authentic was especially important, and Braham spent a further seven weeks after the Leavesden shoot in Gabon shooting background plates and landscapes.

“Tarzan is a very old property, since its inception by Burroughs in the early 1900s, and there was a great opportunity to tell the story with a contemporary perspective,” says Braham. “I was attracted to the project as it’s a great adventure, with real characters, expressive emotion and true passion. Along with the opportunity to work with David at the helm, the ambitious scale and scope of the movie was of great appeal. I really felt we could make a great looking movie.”

Braham says initial discussions with Yates about figuring out the visual ideas for the production were long, “because that’s often the hardest part of making any movie. The idea was to make an expressive, immersive movie using the counterpoint between intimacy on the one hand, and scale on the other, to create a dynamic, big-screen experience.”

He continues. “This might sound obvious, but you have to understand our rationale. David is open to counter-intuitive thinking and we did not want to be reverent in our approach. We wanted the movie to be expressive in the way that the camera is inside the story, up close with the characters and their emotional journeys, rather than being outside, observational and marvelling at the landscapes. It had to be dynamic in the way that the camera moves and frames the action. And we wanted it to be cinematic in a way that made the jungle exciting, dark and dangerous – this sort of environment can look really dull and boring if you’re not careful.

“So we came up with a methodology to build and shoot as much as we could in the studio, to shoot backgrounds and aerials at a later date and join things up in post production. There are some really brilliant people out there who will engage with you on a challenge like this. Furthermore, one of the joys of filmmaking today is that you can approach manufacturers and design the technology around your idea, in ways you could never really do before. You no longer have to pick up equipment from the shelf and just go with that. You can start with a blank piece of paper and really mould what you want to suit the movie.”

On the technology side, Braham says it was fortunate that pre-production coincided with the arrival of the 6K RED Dragon camera. “Physically it’s a very small camera, not much larger than a Hasselblad, and has powerful, large format image capture capabilities. I could see the possibility of using it in all manner of different situations on-set. Jarred Land and the team at RED proved very helpful and responsive in making physical changes to the camera body to enable what I wanted to do, along with various updates to the software and workflow functions.”

After extensive testing of a wide selection of lenses that would suit the camera’s 6K sensor, and the production’s 2.40:1 aspect ratio, Braham settled on Leica Summicrons. These were tuned to his visual predilection by the optical engineering team at Panavision.

“The Summicrons were not just better in terms of bokeh and accurate geometry for the VFX teams, they also looked really beautiful on the jungle and the actors,” he exclaims. “They were perfect for capturing Tarzan’s towering physicality. Alexander had made himself unbelievably fit for the part, and we could so easily have thrown away his hard work with the wrong lens choice.”

"We wanted an exciting and dangerous aesthetic to the rain forest sets and the torrential, monsoon downpours. The sets were huge in scale, and we spent a lot of time together doing camera and lens tests, experimenting with every photographic trick in the book."

- Henry Braham BSC

With this camera and lens combination, Braham says he had the versatility to shoot the entire visual needs of the production – from gritty and dynamic action moves via handheld, Steadicam, cranes, wires and dolly, through to more controlled and intimate macro photography of fauna, flora and flesh.

“Tarzan has animal sensitivity to the environment, and as part of the visual language of the movie we were able to go around the Leavesden studio sets with the actors and shoot material that revealed the intimate connection between them and the environment,” he explains.

Regarding one of the brilliant people on the production, Braham says that working closely with production designer Stuart Craig proved key in helping to achieve the dynamic, big screen experience.

“We wanted an exciting and dangerous aesthetic to the rain forest sets and the torrential, monsoon downpours,” he says. “The sets were huge in scale, and we spent a lot of time together doing camera and lens tests, experimenting with every photographic trick in the book, looking at how best to render a variety of backdrops. In the end we settled on a range of painted scenic backdrops, rather than shooting bluescreens. Thanks to Stuart, his understanding of paint techniques and the wonderful skills of his amazing team, I had great flexibility and huge control in the studio.”

Discussing his approach to lighting The Legend Of Tarzan, Braham says, “I don’t light shots, I light sets – so the camera can go anywhere within them. This was especially important with the dynamic and fluid camera moves we wanted. I worked for months ahead of production to create different emotional states in the production with intense light and intense dark. My lighting plan was based on truth and reality – by which I mean I wanted the audience to really believe in the source of the light. As we were shooting large exterior jungle sets inside the Leavesden stages, we had to have complete coverage of ambient daylight from above. This meant having a huge, controllable rig that was capable of changing between different weather and light conditions.”

He adds: “I am not sure there’s anything extraordinary in this approach, but we were all surprised at how well it worked. When you watch the final movie you do not get the sense that a vast bulk of it was shot in a studio in Watford.”

Braham says the working regime on the UK leg of the movie was based on six-day-weeks, but limited to 8am to 6pm each day. “In those ten hours you can achieve total concentration, with a great rhythm, and consequently get a huge amount of work done. The crew love it too. With longer hours, the pace and concentration is very different.”

After wrapping production in the UK, Braham went to Gabon for seven weeks to shoot aerials and backplates. The African technical advisor, Josh Ponte, who had originally worked in Gabon on gorilla reintroduction programmes, provided great insight into the country and excellent connections to the president and his office. Braham decided to concentrate work in a central area of the jungle to maximise use of the fast-changing weather. The team also camped in the jungle for some of the most remote waterfalls. Given the challenges of the landscape, all footage was shot from a helicopter. For the VFX plates, Braham used a six-by-6K camera array system built for the project by Shotover in New Zealand. Often this rig was suspended from a line of around 50ft in length to prevent prop-wash from disturbing water and foliage, while the second technical support and safety helicopter was positioned behind to help with correct vertical positioning of the camera array. Braham also used a single camera Shotover for the landscape photography and worked closely with his long-term film pilot Fred North on what was a highly-complex logistical aerial shoot.

“I have shot in wildernesses before, such as the Arctic, but never in a vast expanse of jungle, where there’s no safe landing place and you can’t dial 999 in the event of anything going wrong,” he says. “I knew every scene of the movie backwards and what kind of light I needed to capture to help the VFX teams match the background and foreground elements together in post.”

Typically the unit would lift off at 4am, before first light, to do pre-sunrise and sunrise photography. Once back at base camp, a mobile lab – set-up and operated by Technicolor, harnessing a colour-managed workflow specified by DI grader Peter Doyle – processed the footage and transmitted the deliverables back via mobile satellite to the post team in the UK. After some afternoon rest and relaxation, the camera team would take off again for evening shoots, with the resulting footage similarly processed and transferred during the night.

“The way I shoot digitally is exactly how I shoot with film,” says Braham. “I don’t do anything on set. I prefer it that my digital filmstock and the various deliverables are developed and processed by a lab to my specific colour requirement. These days there are a huge number of people who need be in the communication loop about the visual intent of the movie. Therefore, it’s crucial that your workflow is built on a rock, and that the artistic intent and colour integrity are transferred intact throughout the whole process.”

In this regard Braham is equally thankful for Doyle’s brilliant talents. “Peter is great at original thought, and understands the significance of preserving the look and the colour from source. He helped establish an ACES colour pipeline on the production, and designed the blueprint for the workflow from the Leavesden and Gabon shoots.”

Braham completed the DI with Doyle at Technicolor in London. “We focussed on the usual things such as skin tones, the interplay of highlight and shadow, and finessing the colour arc across the movie. But Peter is an unusual combination of photographic aesthete and technical authority. Whilst there was some grain added to embed the movie and help the suspension of disbelief, we tried hard not to put a veil between the audience and the screen, and you are not aware of that in the final projected image.”

Braham concludes: “Production is all about collaboration. It’s a team effort involving direction, production design, camera, editing, VFX, DI and technology vendors. We evolved The Legend of Tarzan together, as a collaborative effort, and I think it worked really well. The end result is the sort of movie I would want to go to see at the cinema.”