EXECUTION IS EVERYTHING

Oscar-winning DP Erik Messerschmidt ASC re-teams with David Fincher for a live-action comic book adaptation that required a meticulous approach to its cinematography.

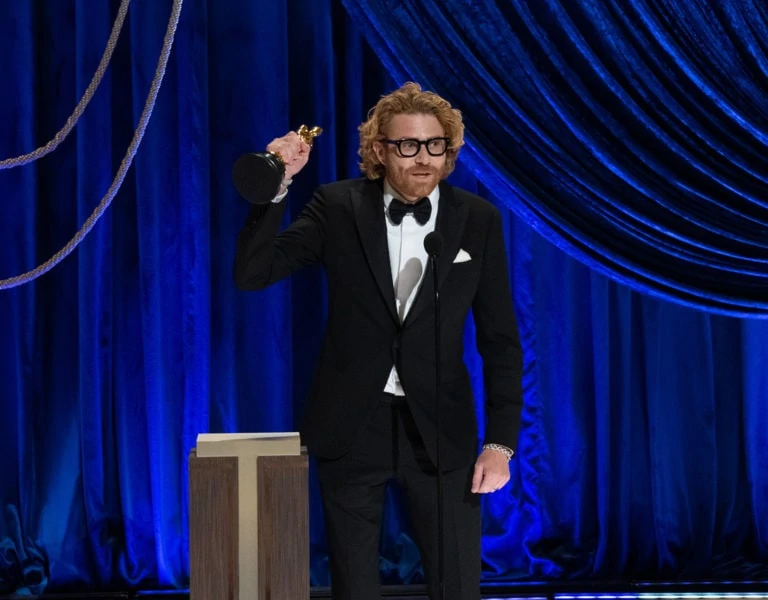

When Erik Messerschmidt ASC got the call from David Fincher to work on his new film The Killer, it was an offer that arrived almost as stealthily as its lethal protagonist. “He only ever [asks] once he knows he’s going to make the film,” says the American-born cinematographer, who previously collaborated with Fincher across two seasons of the Netflix series Mindhunter (2017-2019) and the acclaimed Hollywood-set period tale Mank (2020), which won Messerschmidt an Academy Award for Best Cinematography. The Killer, an adaptation of the French graphic novel, written by Alexis “Matz” Nolent, offered a whole different set of challenges, however.

This tense, taut thriller follows a nameless assassin, played by Michael Fassbender, who is fighting for his life after a job he undertakes in Paris goes disastrously wrong. “When I first read it, I was so excited about how little dialogue is in the film. It’s all voiceover,” explains Messerschmidt. “Normally, when you shoot a scene in a narrative film, you’re shooting actors predominantly talking to each other. And this film…on the set it was quite a quiet place. Which is really, really interesting. And it changes the dynamic enormously.”

To borrow the film’s cunning tagline, “Execution is everything”, and making The Killer became a meticulous experience for Messerschmidt and his team. Choreographing the camera to reflect the perspective of Fassbender’s killer, as he watches from the shadows, required absolute perfection. “It became very much about precision,” he says. “It’s an enormous amount of pressure on the camera operator [Brian S. Osmond] on this film.” Every step of the background artists was accounted for, like an elaborate dance. “So, it’s all sort of in concert…[that] is the intention most of the time.”

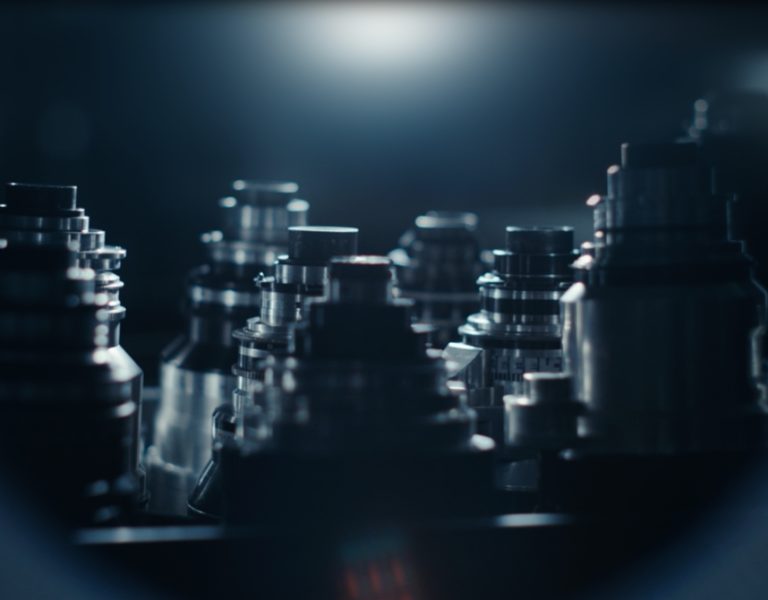

Shot on digital, The Killer saw Messerschmidt employ the RED V-Raptor ST camera. “We love the tonal qualities of the sensor. The resolution. It’s an 8K camera. We shoot with a centre extraction for reframe and stabilisation. So if you shoot it in 6K or 7K, you have an enormous amount of room outside of the frame to adjust. And that over-sampling, if you will, I think gives us enormous freedom in colour grading, particularly when it comes to working in extremely low light. A lot of the film was shot with very low light levels, so the camera performs extraordinarily well in those situations.”

With the film echoing the muted yellow and green palette of the original graphic novel, Messerschmidt wanted to light the scenes as organically as possible. “The way David blocks scenes and structures scenes, he’s very considerate of the challenges he’s putting on the cinematographer. He’s very aware of what the background is.” Take the moments with Fassbender’s character in his vehicle. “If the car is meant to be lit, [he would ask] ‘Do you want me to put the car underneath that streetlight? Will that help you?’ He’s very accommodating as a director, and considerate about the entire process, which is enormously helpful, obviously.”

Messerschmidt’s approach to lighting errs on the side of naturalism wherever possible. “Where I feel like the work looks the best is when it’s utilising something that actually exists. So a lot of the discussions that I have are with Don Burt, the production designer. Are there ceiling lights? Are there floor lamps? Where are the windows? How big are the windows? What direction would this set face if it was in the real world? Is it north facing? Is there a south facing?” In the Paris-set scenes, for example, Messerschmidt primarily used available street lighting. “If anything, we turned everything behind the camera off.”

One major exception, however, was a scene much later in the film, where Fassbender’s killer confronts one of the assassins – played by Tilda Swinton – who has been sent to kill him after his botched job in Paris. While she is eating in a classy New York restaurant, he joins her at her table. Actually shot at a real eatery in Chicago, cherry pickers were set up outside the establishment, with SkyPanel S360-C LEDs used to reflect light from the nearby water and through the window where they’re seated.

Inside the restaurant, Messerschmidt elected to light them from below, using LED balls placed on the table. “I would say the vast majority of the light in that scene on both of them is coming from the lamp on the table, which were on every table.” Partly, it was a huge time-saver. “Without something like that, without candles or some sort of table lamp, you end up having to put in all this false backlight to create depth and it can get messy really quick. And we had a lot of coverage in that scene. There are low angles and tight angles and high angles looking down on her and I didn’t want to get in a situation where we had to do a bunch of re-lighting every setup.”

Certain requirements saw Messerschmidt switch to the RED Komodo camera, notably as he shot background plates for the opening Paris sequence, where Fassbender’s character is staking out his mark from an empty apartment on the opposite side of the street. Fincher was set on the idea of the target’s penthouse boasting huge floor-to-ceiling windows. “Part of the problem is…Paris doesn’t really have windows like that,” says Messerschmidt. “We spent a lot of time looking for it in Paris. And it just doesn’t exist because Paris has very specific design rules for spacing between windows.”

With Fincher determined not to change the architecture of the scene, it made for a hugely complex jigsaw puzzle for he and Messerschmidt to solve. Initially, the team went to Paris – without Fassbender – to shoot the action from the killer’s point of view. The Komodo’s compact size made it an ideal choice. “We had to fit nine cameras, I think, in a very small window in Paris,” says the cinematographer. “And we wanted to do it all as one big, choreographed piece of action…in matching lights. So, we had to shoot nine cameras at the same time, and we would run the whole scene…all the extras on the street doing their daily duties.”

The interior of the apartment where Fassbender’s character is situated was then built months later on a virtual soundstage in New Orleans. “That was lit predominantly by an LED screen, using the plates [we shot in Paris], so that we got the same sort of interactive light from the Paris street onto Michael,” explains Messerschmidt. The third element of the scene – the people in the apartment that the killer is watching – was completed later. A set was built, complete with those high windows Fincher wanted. This was then digitally added in post onto the façade of the Parisian building that was shot earlier. “So that is a real building that exists in Paris. But the penthouse does not.”

For his lens choice, Messerschmidt found comfort in the familiar. “We shot almost all the film on Leica Summilux Primes, which we had shot on Mank and Mindhunter prior. So, I really know those lenses quite well at this point,” he notes. “We wanted the film to have certain anamorphic characteristics: blue streak, anamorphic flares…none of those flares are real, by the way! We want things anamorphic could give you, but we wanted to shoot spherical because we needed close focus.”

When it came to shooting the moments of Fassbender’s character using his gun’s scope to line up a target, those POV shots were all achieved using a Fujinon 75-400mm zoom “which is a lens I adore”, Messerschmidt adds. “It’s really fast and really sharp. And it cuts well with the Leica. We wanted those distances when we shot those POVs to be accurate. So, we used an appropriate lens. Sometimes you see POVs, and they’re shot on quite a short lens, but they just move the camera closer, and we were trying to keep geography and distance relative.”

After an intense five-month shoot that also took the production team to the Dominican Republic, where a real house was found to stand in for the killer’s hideout, the film moved into post-production. Like so many major films these days, the process of assembling the film began long before shooting wrapped. And that included the colour grading. Colourist Eric Weidt has worked exclusively with Fincher since 2015, grading Mindhunter and Mank. “He’s in-house, with David,” explains the cinematographer. “It’s an enormous privilege. You don’t have to share the colourist with other films. He’s on the project from the beginning.”

Weidt joined the project in pre-production, only a couple of weeks after Messerschmidt began his work. “Right out of the gate, we were shooting tests and sending it to him and looking at grades and developing a colour pipeline for the film.” Better yet, when the shoot was underway, and editor Kirk Baxter began to assemble dailies, Weidt was on hand to fine-tune the colours, giving Fincher and Messerschmidt a perfect guide. “The next day David and I can look and say, ‘Maybe we should reshoot that close-up because it doesn’t really match.’”

It’s a luxury that the cinematographer is eternally grateful for. “We’d love to think that the film is paint-by-numbers, but the film does take on a life of its own as you’re shooting it. And I think, when the editor is assembling sequences that you may have shot a day or two ago, and then you look at it in context, and you say, ‘I wonder how that would look, if it had a little bit more yellow…’ And that can often influence the next day’s work. It becomes very much like seasoning the sauce and tasting the sauce. That analogy for me works really well. You’re constantly checking yourself.” After all, execution is everything.

–

The Killer is in cinemas and available on Netflix.