DEATH IN VENICE

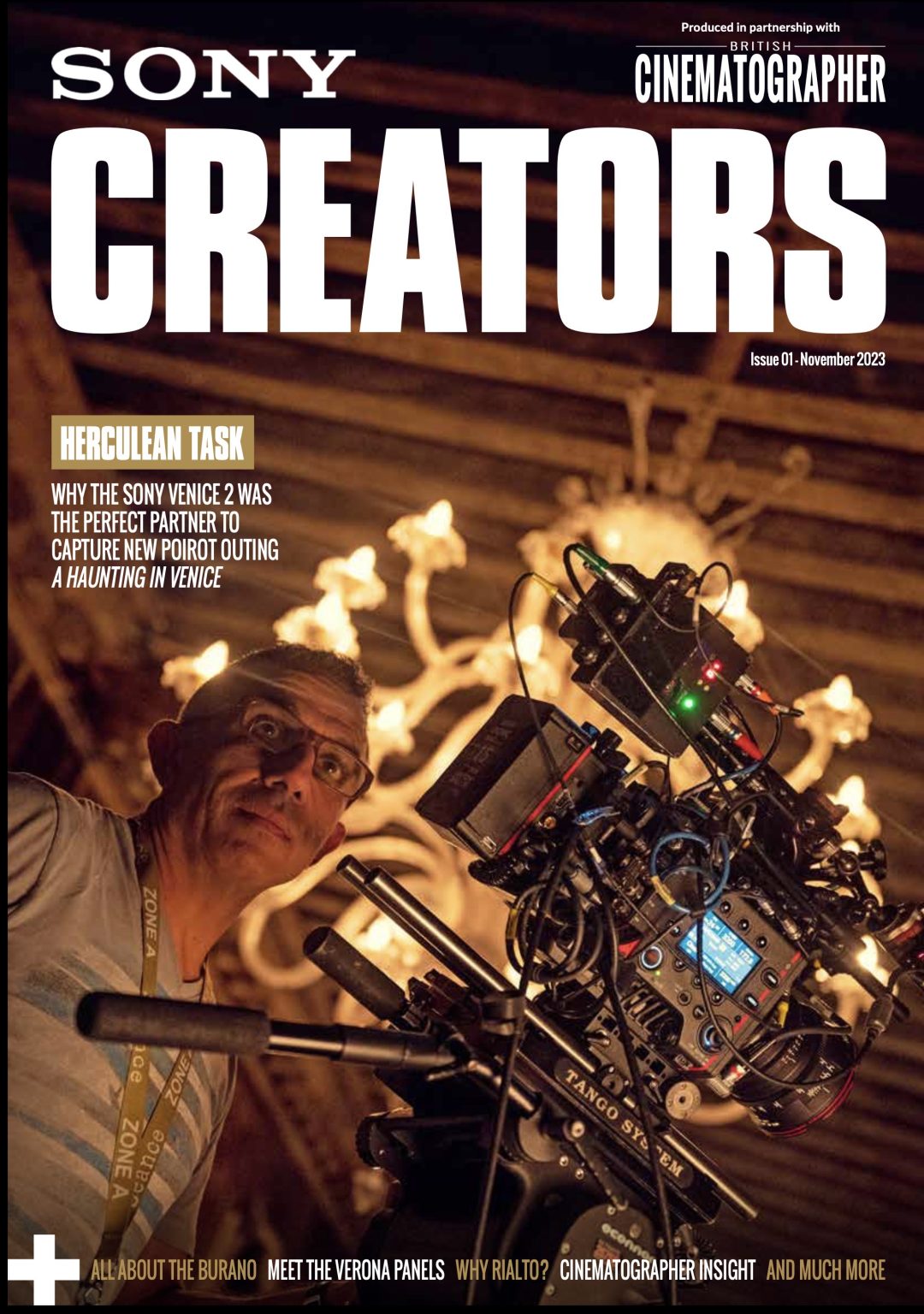

Kenneth Branagh reprises his role as Hercule Poirot in A Haunting in Venice. Haris Zambarloukos BSC GSC on the film explains how he used the aptly named Sony VENICE 2 for a brand-new attempt at a story released 54 years ago.

Venice, with its labyrinthine canals, decaying grandeur and eerie ambiance, is a cinematic paradise for filmmakers in the horror, thriller and mystery genres. Its hauntingly beautiful architecture and mist-shrouded waterways in bleaker months create a unique backdrop that amplifies tension and intrigue. Films like Don’t Look Now (1973) masterfully exploit its otherworldly charm, using the city’s ghostly and ancient buildings to great effect. The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) highlighted its duality as a city of both glamour and secrecy, adding layers to the mystery.

It stands to reason then that director Kenneth Branagh, reprising his role as the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, decided to rename Agatha Christie’s 1969 novel Hallowe’en Party to A Haunting in Venice for its big screen adaptation – and transported from England to the eponymous city in the course of events, highlighting the story’s Gothic elements.

In this outing, the retired investigator is drawn into the intricate puzzle of a murder that occurs during a séance in which he participated. The ensemble cast boasts Camille Cottin, Jamie Dornan and Michelle Yeoh, while cinematography duties were again handed to Haris Zambarloukos BSC GSC, following his excellent work on Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile.

Due to Venice’s unique layout and limited accessibility, the team undertook extensive reconnaissance missions on foot, exploring the city day and night. Their persistent efforts eventually led them to a palazzo shrouded in an aura of haunting mystery.

However, the exteriors of these grand old buildings often belie what’s inside them. “Like most palazzos, this one has been converted into apartments with modern features,” Zambarloukos explains. “That made it impossible to marry the interior and exterior, so the interior was built at Pinewood Studios and whilst the boat house entrance on the canal is a real Venice location, the team built smaller versions of both, took the gondolas from Italy to the UK and had entrances and exits in the actual city. It was a composite set.”

The storyline unfolds within the confines of a single night at the palazzo. Delving into the historical context of architecture and lighting during that era, there were traditional lighting fixtures and a reliance on candle light.

“We used a combination of both,” explains Zambarloukos. “We were quite precise regarding what kind of bees wax and candles they used, and we also used gas light fittings and oil lamps – it was pretty authentic in that respect.”

However, creating an authentic look requires a certain approach to filming, depending what one wants to achieve.

“One of the issues with shooting in low light and with candle light is historically, whether digital or film, they were almost on par – in 500 for film, 800ASA for digital cameras we always had to rely on shooting much faster lenses at an F stop that’s below 2 – often T1.4,” he adds.

Gaffer Dan Lowe introduced many of the period film and theatre lights that were used on the night club scene in Death on the Nile for practical lighting in the palazzo. The art department also brought period theatrical lighting.

“We used LED fixtures like Luxor and Vortex outside the windows with the odd Tungsten Molebeam but all the interior lighting came from period tungsten fixtures, candles, oil lamps and practical gas lighting in the walls,” Zambarloukos says.

Joe McGee, a practical electrician, has worked alongside Zambarloukos for almost 20 years. He

was on hand again to make sure everything was connected as required.

“He wires everything and makes them DMX-able, but he also builds things,” Zambarloukos continues. “One of the things Dan and I wanted to do was build what we called a ‘dome light’. It was LED, in amber and tungsten 200K and 2900K, battery-operated and DMX-able so never needed to be plugged in to a socket. You can place it like a candle anywhere we wanted. It was 3D-shaped and 3D printed and even the circuit was quite revolutionary the way we made it that quickly and to our extremely high specs.”

Zambarloukos is very prescriptive about what he wants to achieve from his work and is prepared to depart from techniques established by some of the best filmmakers the industry has ever seen.

“The great landmark (Stanley Kubrick) film Barry Lyndon was shot with specially made lenses at T.9 – ridiculously shallow depth of field,” he explains. “In all these films, however beautiful they are, there was always one thing that distracted me to some extent for extensive use – it’s one thing to do it for a few scenes – is that you can never get enough depth of field for two eyes to be in focus constantly.”

It’s for that reason that Zambarloukos has always worked at T4 and that was a photographic aspect that he wanted to maintain.

“All the other Poirot films have been shot at between T4 and T8 and rarely did we ever go below that even in candle lit scenes,” he continues.

To facilitate this, he chose the Sony VENICE 2, which, apart from having “the right name” it had a 3200 ASA sensitivity.

“On my initial test it had a really great colour palette,” Zambarloukos says. “Concentrating on those red and warm areas, having a lot of colour separation was important to me because that’s where the face lies and that’s where a lot of the warmer, terracotta colours, umbers and all those kinds of colours exist in Venice and in the architecture. So, you could get that very clearly with that colour palette.”

Director and cinematographer wanted to shoot this film in a slightly different way to the previous Poirot films – the plan was to make the movie much darker and in a more intimate way. The answer was to depart from 2.40 aspect ratio and use 1.85.

Zambarloukos tested Ultra and Auto Panatar 65mm lenses on Murder on the Orient Express but didn’t use them in the end. However, he thought they might work well with the Sony VENICE 2 so he tested them again. The Panatars have a 1.25 anamorphic squeeze.

“The lenses turn 65mm to a 2.67 aspect ratio,” Zambarloukos explains. “They were created for Ben-Hur, but they’d been sitting at Panavision and had rarely come out because they don’t have much use in the 35 and Super 35 world. But in the modern times of VistaVision size sensors that we now have, they’ve come into play because they give you a 1.85 aspect ratio to a full frame sensor.”

He used 1.85:1 aspect ratio on Branagh’s film Belfast and found a way to use negative space and architecture in an interesting way. “That meant we could leave more headroom, plant things over to the side a bit more and have all this kind of negative space,” he continues. “It also meant weather could play a part. We could have a window in frame, wind, rain and thunder and anything effects that affected mood.”

The piano nobile (the architectural term for the main floor of a palazzo) is a beautiful space with a high ceiling, so the hope was the 1.85 would help maintain all the windows and the atmosphere they wanted. So, Zambarloukos paired the Sony VENICE 2 with Auto and Ultra Panatars, shot at 3200 at a T4 in 1.85 aspect ratios, throughout the whole film.

He adds that the Sony VENICE 2 “in its traditional set up is a decent workable size and weight” to work with.

“It’s good enough for Steadicam, crane and handheld – and we were fortunate to be given a prototype Rialto,” he continues. “It wasn’t just useful for being lightweight, we also had a certain scheme to the way we shot this. The Rialto helped us get into tight spaces on a composite set.” He cites one of the key scenes that involves “a spiralling stairway” that leads up to a big moment involving Yeoh’s character, the clairvoyant Joyce Reynolds. “That stairwell is linked to the rest of the set,” he says. “Fully composite with no moving walls so the Rialto got a lot of those unique and interesting angles. Its size, for handheld and weight is balanced. The Ultra and Auto Panatars are a bit front heavy on a Rialto, but they are older lenses.”

The plan was to try to “shoot as much as possible in camera” and the team tried to incorporate painted and photographic backings behind the set windows, real SFX rain and even miniature work into the filmmaking. “Wherever we thought we had reached the limit of what in camera effects could achieve, our amazing VFX supervisor Artemis Oikonomopoulou brought great expertise and artistry in creating seamless VFX work into the film,” Zambarloukos continues. “Also, our UK team worked in conjunction with our Italian crew and we had incredible support and artistry from our colleagues in Venice.”

Poirot graced the pages of over 30 novels, along with numerous short stories and plays. This vast reservoir of source material provides ample opportunities for adaptation, should Branagh decide to explore further mysteries in the future. Does that mean there’s already another film in the mix?

“I always treat each film with Ken like it’s my first and last,” Zambarloukos says.

While that might be true, it would take a brave person to bet against them collaborating on Poirot murder mysteries in the future.

Find out more here.

–

Words: Robert Shepherd