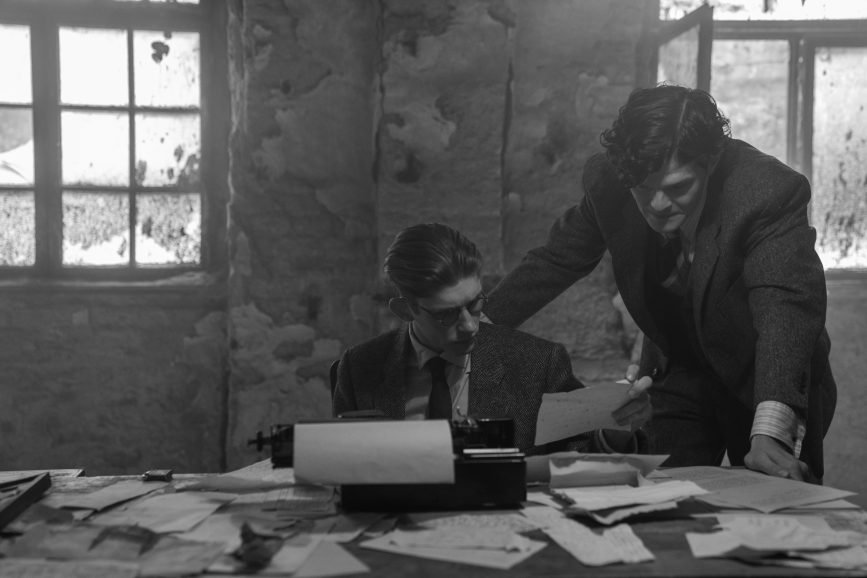

A LIFE IN MONOCHROME

Samuel Beckett, a towering figure in 20th-century literature, is the subject of the biopic Dance First. Cinematographer Antonio Paladino sheds light on the choice of black-and-white cinematography and the equipment deployed to bring the director’s vision to the big screen.

Numerous films, stage productions and other adaptations have masterfully captured Samuel Beckett’s distinctive style and existential themes, yet there remains a striking scarcity of cinematic endeavours dedicated solely to the reclusive Irish playwright who famously wrote Waiting for Godot. This dearth resonates profoundly with Beckett’s own aversion to the limelight. Despite being one of the most celebrated writers of his generation, he fervently shunned attention, preferring to let his words and characters take centre stage.

In that sense, the theatrical biopic, Dance First, derived from Beckett’s philosophy of “Dance first, think later”, is pioneering.

Starring Gabriel Byrne in the lead role, the cast also includes Fionn O’Shea as the youthful protagonist and Aidan Gillen as Beckett’s mentor and friend, James Joyce.

Having a paucity of projects from which to gain inspiration or learn from the mistakes of others meant the director James Marsh had a blank canvas with which to make the film.

Cinematographer Antonio Paladino (The Ring of the Buddha) explains how the visionary made a deliberate decision to film Samuel Beckett’s life story and characters in (mostly) black-and-white to evoke the existential tension and minimalist aesthetic found in Beckett’s own work.

“His literature often deals with themes of despair, emptiness, and the human condition,” he says. “The black-and-white medium can pare down the visual elements to their most basic forms, allowing audiences to engage more deeply with the characters and the narrative, devoid of the distractions that colour might otherwise introduce.”

Of course, monochrome cinematography also pays homage to the era in which Beckett wrote many of his most famous pieces. “The reduced colour palette serves to focus the audience’s attention on contrasts, movements, and expressions, thereby heightening the emotional impact,” Paladino continues. “We wanted to create an atmosphere that captures the internal landscape of Beckett’s psyche as much as his external world.”

In the absence of colour, other elements like composition, lighting and texture become significantly more important. These elements would have to be meticulously planned to ensure they effectively conveyed the intricate emotions that Beckett grappled with, including feelings of guilt that persisted throughout his life.

“Translating a real-life story, especially one as fraught with emotional and intellectual complexity as Samuel Beckett’s, was certainly a challenging task as a cinematographer,” Paladino concedes. “James Marsh’s choice to do so in black and white added an additional layer of difficulty but also offered unique opportunities for artistic expression.

After an extensive testing period, he arrived at an undeniable consensus: black-and-white is the most fitting medium for this film. On this occasion the budget provisions meant that Antonio was unable to use his preferred camera, the VENICE 2, so opted for the VENICE. He then had to decide on lenses, having tested a number of different series during prep and studied the results on a big screen. It was soon “clear to everyone in the screening room” that the three modern lenses that he tested would not give us the sensibility he needed to depict timelessness and nostalgia.

Instead, he went with vintage prime lenses (mainly 35mm and 50mm) for most of the shoot. The rationale behind his decision was based on the fact he was looking for a camera that would produce the best results in very low light situations.

“They offer natural imperfections and a softer image that modern lenses often lack, thereby imbuing the film with a kind of humanity and frailty that fits well with Beckett’s themes,” Paladino continues. “We wanted to remain true to the emotional tone of Beckett’s works and life and the combination of the Sony VENICE and vintage lenses allowed us to capture a timeless and emotive visual style. The Sony Rialto rig’s compact size is great for tight shooting locations.”

Whilst the film is almost all in monochrome, audiences will notice how the film ingeniously transitions from black-and-white to colour, skilfully capturing the evolution of Beckett from a young, hopeful writer to a disenchanted yet wiser older man. “We hoped that this could act as a visual cue for the audience, signifying a phase of transformation or realisation in his life,” Paladino says.

Knowing he had the VENICE also meant Paladino could plan ahead, such as for scenes that took place in a dark basement, a moonlit apartment and a candlelit bar during a power cut.

“When my colleague Frank Griebe said that he had shot a scene with 10,000 ASA and made it work in the grading suite, I knew that this will be the camera for my show,” he continues. “The Sony VENICE provides the advantage of digital filmmaking, while still offering a cinematic texture that can resemble film when lit and exposed on set in a certain way and treated correctly in post-production.”

The period Beckett lived in – early to mid-20th century – also influenced Paladino in how he lit the biopic. “When Beckett was alive, lighting in films was largely influenced by the studio system, with high-key lighting common in Hollywood and more experimental, lower-key lighting techniques emerging in European cinema,” he says. “To emphasise the harsh realities and themes within Beckett’s life and work, you might use hard lighting, creating strong contrasts and sharp shadows on the actor’s face. This could serve to highlight the stark choices and circumstances Beckett often wrote about. However, I deliberately chose soft lighting to humanise Beckett, presenting him as a more relatable, empathetic figure.”

The aforementioned low-key scenes represented a challenge from a cinematography standpoint. “For dark scenes I always tend to ‘under light’ without ‘under exposing’,” he adds. “These scenes required the camera to perform exceptionally well in dim light to capture the nuanced emotions of the characters and the intricate details of the set.”

That is “precisely why” he opted for the Sony VENICE. The camera’s capability to shoot at a native ISO of 2,500, expandable up to a stunning 10,000 ASA, was not just a technical specification on paper “but a real-world saviour” for the team. What’s more, the dynamic range it offered gave Paladino the flexibility to film in conditions “that would be prohibitive for many other cameras” on the market. “Candles and lanterns were our only source of illumination, but the Sony VENICE high sensitivity made my life easy,” he adds.

In some cases, Paladino used minimal supplemental lighting to enhance features or to establish a particular mood. The VENICE’s sensitivity made it possible for him to maintain authenticity, capturing the actors’ expressions and the period-correct set pieces with surprising clarity. This high sensitivity also meant less noise, greater depth, and a more organic feel to the shots.

“For one memorable scene set in a basement during a power cut, the only lighting came from a handful of candles scattered around the room,” he recalls. “Yet, the Sony VENICE managed to capture not just the faces and actions of the characters, but also the dark, claustrophobic atmosphere of the setting. With any other camera, we would’ve likely had to compromise on the aesthetic or even the storyline. Raising the ISO to 5,000 ASA for these specific scenes provided an unexpected advantage.”

When it came to balancing the need to capture authentic details of the era while infusing his own creative interpretation, Paladino called on production designer Damien Creagh, who delved deep into any available footage and photos from the era and shared them with the team.

“His office, where every wall was covered with these images, was my happy place to go to during pre-production,” he explains. “This was essential to understand the zeitgeist, the social and political climate, and the aesthetics of the time. I consulted experts to understand the artificial lighting that was used in this era. however, we chose to have some liberties too. I stayed away from using gas lighting, that was used during this time. At the end, film making is a practical process too. you have to work within a certain time and budget and consider strict health and safety rules.”

Paladino says using contrast, shades and light “can create a mesmerising cinematic moment” and the introduction of a character can be a monumental experience – something he very much likes to celebrate.

“I wanted the introducing of Suzanne (Beckett’s future wife) to be poetic and powerful, encapsulating the transformative essence of love at first sight,” he explains. “The darkness of a bar, filled with smoke and chatter, served to heighten the impact of Suzanne’s entry. It’s like the whole world goes quiet for a moment and all we see is her in a white dress, bathed in this almost angelic glow.”

He also explains how shadows can be a powerful tool in conveying emotion. “For instance, when Beckett had to escape Paris from Nazi occupation, he plunged into metaphorical and literal darkness, accentuated by heavy shadowing which represent a period of depression and uncertainty,” Paladino adds.

Furthermore, the team managed to shoot the 100-minute film in a remarkably brief span of 25 days, requiring them to achieve an impressive rate of four minutes of footage per day. This accomplishment becomes even more impressive when one considers the inherent complexity associated with a period piece, which left very little room for deliberation or last-minute changes on set.

Skillfully balancing historical accuracy with creative interpretation, Dance First becomes a poignant testament to Beckett’s enduring impact and the profound visual language that underscores his legacy.

–

Words: Robert Shepherd