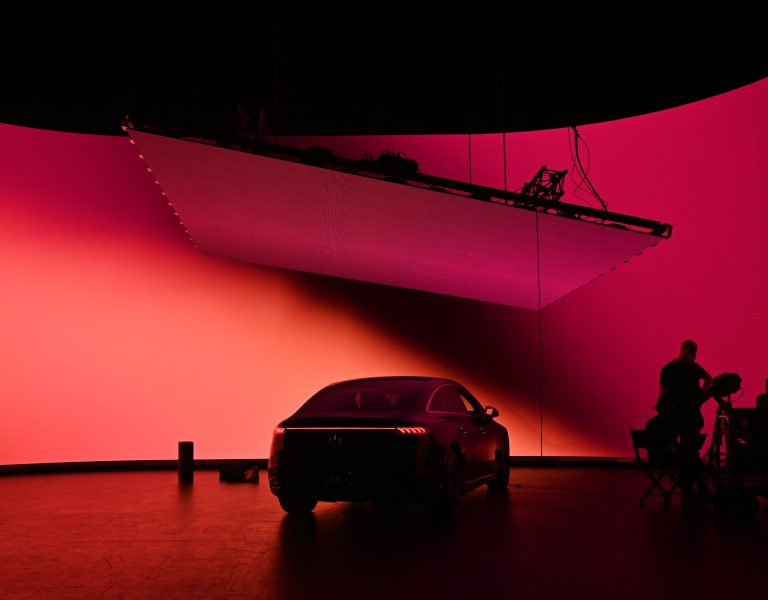

Vehicle interior shoots are right at home on a virtual production stage. DPs Björn Charpentier SBC and Charlie Gruet share their processes when filming in the volume.

Of all the applications to which virtual production has been put, the car interior has probably been the most immediately successful.

Virtual production has its origins in the earliest days of cinema, when traditional back projection became famous for wobbly car interiors. By the time the Wachowskis used back projection to deliberately heighten the unreality of a virtual world in The Matrix, the technique had improved so much that it’s arguable whether that creative choice actually had the intended effect. Now, there’s even more sophistication – a virtual production stage can enrich what was once called poor-man’s process to the point of doing far more than could practically be done on a real road.

Björn Charpentier SBC’s credit history on feature films goes back as far as 2012, with recent highlights including Fractured and The Negotiator. His work on the second season of Gangs of London includes several in-car sequences, with one in particular being, “elaborate. I was working with Corin Hardy, the director, who was also showrunner. For the last episode we had twenty minutes of car sequences. He didn’t want to shoot standard shot-reverse shot. For an epic finale, he wanted it to be bigger, and we were looking at some very inspiring car sequences. Two came to mind – one was from War of the Worlds, and the other was Children of Men.”

With the great ambitions clearly defined, Charpentier evaluated his options carefully. “We shot in the winter in London, so we had very limited daylight. And let’s say you have a stretch of road. It’s a given length, and if the light changes, you have to go back to the start.” With a variety of advanced camera moves schedules, the production shot car-to-car exteriors on an Ukraine arm, gathering plates of the environment at the same time. “We didn’t get just the wide shots, we got some tighter shots on the actors from outside the car, then anything close was virtual production. We also shot plates of the road at two different heights depending on what we were doing. We shot that quite early, first or second week of production, and the last week we shot the volume, so they had time to stitch everything together.”

Working on a virtual production stage, Charpentier and his crew could do things that would have been difficult or impossible even on a process trailer. “We asked production to buy two cars, and we cut the roof out of one in sections,” he says. “We put two sliders on top of each other, with an Alexa Mini with very small Cooke lenses, on the DJI RS2. The key grip was outside the car, and we were on walkies. It became a very free way of shooting inside the car. The camera might start inside the car, track back with the passenger, rotate around the front windshield, go back inside the car… those are technically impossible to shoot on the roads, but they made it very entertaining for the audience.”

Background plates are, arguably, simpler to use than a scene rendered in Unreal Engine, although the geometry of the real and virtual worlds must still match. Charpentier quickly developed a shorthand approach. “Before we shot anything, we put the camera [square onto] the car at eye level. Then we positioned the background plate in the same perspective, and once those were aligned, I was able to start looking for shots. Still, there were shots where we screwed up by putting the horizon a bit too high or a bit too low. It becomes very subjective – is the car floating above the road or beneath the road? Those are tricky things to do, especially as we had several cars at different heights. We had very careful notes on what plate was meant for which car!”

Like a certain famous science fiction engineer, though, virtual production can’t break the laws of physics. “We were shooting one sequence where the director wanted to have the camera behind the car, so we could see the car next to it. Even when everything was aligned, it looked fake, and we couldn’t see why. Our post super saw that if you shot that in the real world, if a car is driving next to you and focus is on the back of your car, the car to the left of you should also be in focus. But on a volume the background picture is twenty feet further away. The car has to be in focus but because [the wall] is further away, it’s out of focus. Oh well, we can’t shoot that wide on a volume and have elements at the same focus field, unless it’s really there. We had to learn that while we were shooting!”

In circumstances with faster turnarounds and lower budgets, the ability to avoid a traditionally inconvenient day on a process trailer can be even more valuable. Charlie Gruet has been involved since the 1990s, coming up through various roles in commercials and still photography, then moving into cinematography in the early 2000s. His most recent work includes film unit material for Saturday Night Live and The Other Two,created by SNL writers Chris Kelly and Sarah Schneider.

“Working on the way we did on SNL, it was script Wednesday, scout Thursday, shoot Friday, and it’d be out on Saturday. One of the things that happens in New York is that traffic is a nightmare, and shooting on a process trailer is a nightmare because you drive five feet and you’re stuck in traffic, then you drive five feet more and you’re stuck in traffic again. When you’re working on hundred-million-dollar budgets, you can shut down an avenue and have thirty police officers controlling traffic. Where you have one or two million per episode, you don’t have the time, money, or resources.”

Local service providers seemed aware of this, and Gruet describes “this desire, over the last five or six years, to use LED walls to shoot car stuff specifically. There’s one called Carstage in Long Island City. That was a great idea. On season three of The Other Two we went to Carstage and it vastly improved what we were able to get, in terms of page count and in terms of creative vision.” One task in particular would have been difficult to recreate with more traditional techniques. “It was a car speeding down the highway, with one of our lead characters going back to his reunion to boast and brag about how he is doing so well. As he’s going, another car pulls up to him and they’re having a conversation from car to car. There’s no way we’d be able to do this practically, in the time frame we were given and with the budget we had to work with.”

Making that happen, Gruet says, means accepting some prerequisites. “There’s this idea that it’ll be quick. As we were doing prep on season three of The Other Two, we thought, OK, we’ll just shoot that on the LED wall. Next thing, it’s 14 pages of stuff in four different cars, a day vibe, a country night vibe, a city vibe. It’s still work, it’s still lighting and camera and reflections. Now, can you get more done on the LED wall than on a process trailer? Yes, but it’s not infinite. Finding the right plates is absolutely the most important thing. You have to make sure that two-minute loop of what you’re getting is exactly what you need. For our show, we would just keep the camera rolling a lot. We had to make sure our two-minute loop of the background was going to work for all of the scenes.”

To say that car interiors have been an early hit for virtual production seems redundant, though as so often pride might come before a potential fall. “You need to be mindful. It’s not just turnkey. We do need lights, we do need to do stuff to add to it.” Even so, Gruet admits, the advantages are hard to miss. “You can go shoot your car stuff and knock out a high page count of work with a variety of tasks, whereas prior to that when you were on a process trailer it was a really slow endeavour.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes