Home » Features » Tech-nique »

FILTERED IMAGES

DPs past and present discuss their favourite filters and consider the place of physical filtration in a digital world.

“It’s still a question I ask myself every time I put [a filter] in front of the camera: is this something best done in post or is it best done now?” Alex Metcalfe has photographed several award-winning feature films and is a brand ambassador for filters manufacturer Formatt Hitech.

“I never feel like I know a film better than when I’m shooting it,” he says. “We’ve spent days if not weeks working through what the film should look like with the director, so the time of the actual shooting is the time when you should be making these decisions, and you should stand by them.”

Metcalfe recently shot M and M Film Productions’ Fear the Invisible Man, a thriller set mainly in the late 19th century. He used Formatt Hitech’s Gold Supermist diffusion filters which “push the highlights a little bit golden,” generally favouring the 1/8th strength but occasionally stepping up to the 1/4 or 1/2.

“For the flashbacks we used some filters that are no longer generally made – like suede, tobacco – fairly strong colours,” Metcalfe adds.

While many DPs today would leave such colour effects to post-production, Metcalfe points to the benefits which the in-camera approach offers to other departments, allowing them to respond to the filtration and adjust accordingly. “Make-up maybe need to go a bit heavier. The art department might find that some of the tones they’ve put in aren’t resolving well with this particular filter. Film is a collective thing, and if everyone can see at the time where it’s heading, I think it brings a better result.”

For an earlier feature, 2016’s The Lighthouse, Metcalfe wanted to visualise the splintering sanity of two men isolated from the rest of the world. His solution was to have a number of 4”x4” sheets of glass cut to fit his matte box, then to smash each one and loosely tape it back together.

“Because we were shooting at a fairly wide stop, you didn’t see the breaks unless some light hit it,” he explains. “When we wanted to emphasise the characters’ madness, we’d get a torch and put a little bit of light on the lens, and you’d get all these crazy flares going across.”

Natasha Braier ASC ADF has a similarly DIY approach to filters, using a technique she calls “lens painting”. “I feel like in digital… sometimes things are too clean and there’s no room for chemical or physical accidents or aberrations,” she told the Go Creative Show podcast last year, “so I try to mess it up a little bit.”

On her first digital feature, 2016’s The Neon Demon, director Nicolas Winding Refn encouraged Braier to experiment, so she began applying grease from her forehead to the lens to soften certain areas of the frame. By the time she shot Honey Boy in 2019 she had the technique down to a fine art, effectively creating a custom filter for every shot. “I have a whole set of five suitcases with different materials, different powders and liquids and glitters.”

Of course, grease on the lens is not a new trick. Director David Fincher came to the rescue on 1992’s Alien 3 when a glowing pit of “molten steel” was clearly reading on camera as the rig of scaffolding and lamps that it really was. The late Alex Thomson BSC recalled on the DVD commentary: “He just took his finger to his nose and got some nose grease and popped it on the lens and diffused the little spot where the furnace was, and it looked great.”

Thomson was a master of soft focus, working in a time when DPs had no alternative but to make a filtration choice and – as Metcalfe says – stand by it. In a 1982 interview about Excalibur, for which Thomson received an Academy Award nomination, he described the film as “a dream that needed to retain an edge of reality.” He achieved that look by pairing the now-discontinued Harrison & Harrison Black Dot Texture Screen filters with a stocking on the back of the lens.

For 1985’s Legend, director Ridley Scott encouraged Thomson to choose diffusion filters on a shot-by-shot basis. “We ranged freely from gauzes to Low Contrast, Supa Frost, Fogs and Black Dots,” the DP told American Cinematographer, “and in the end I think the results look pretty remarkable.” His peers agreed, honouring Thomson with Best Cinematography at that year’s BSC Awards.

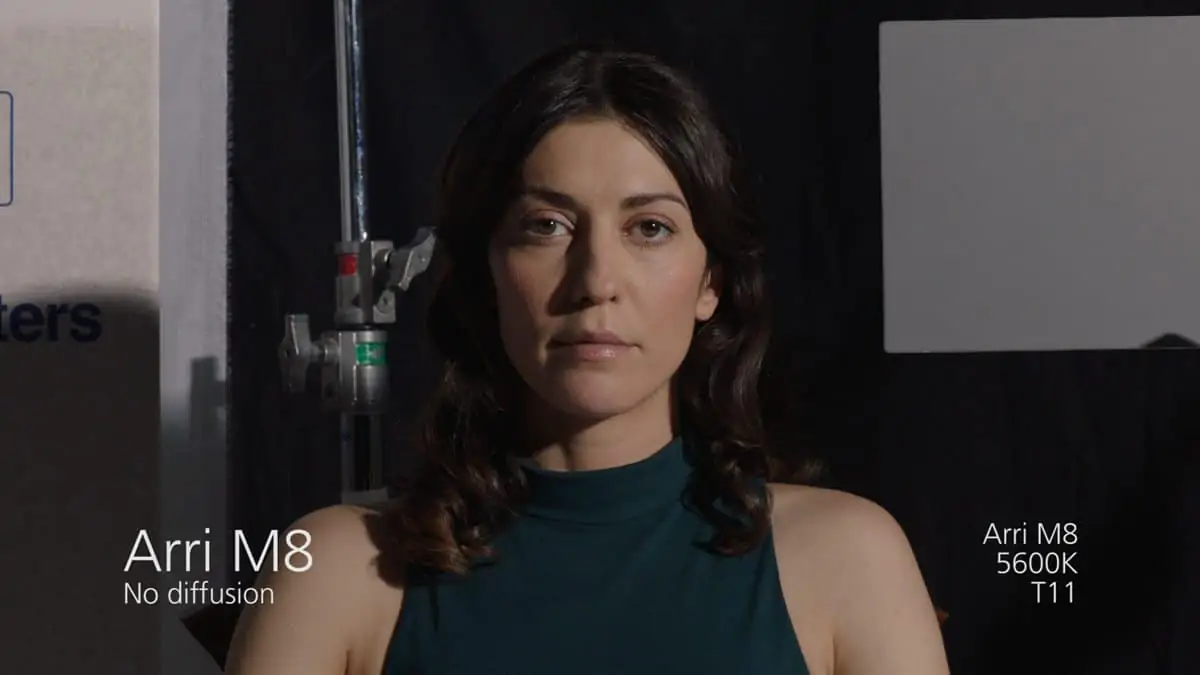

An element of the organic, of randomness, is a desirable quality in diffusion to this day. “There’s crescent moons, there’s lines, there’s full circles,” says Shane Hurlbut ASC. He is describing the shapes acid etched into Tiffen’s Digital Diffusion, a set of filters he helped the company to develop.

Hurlbut, a proponent of Red cameras, aimed to make the highlight clipping of the sensor more organic without creating the blooming or halo effect redolent of existing diffusion, while at the same time subtly diffusing skin. “It’s softness without seeing it,” he says. “You feel it.”

For the Disney+ feature Safety, Hurlbut and Tiffen expanded the range of Digital Diffusion strengths to match the wide gamut of focal lengths the DP was employing, from a heavy 9 on an 8mm lens all the way down to an incredibly subtle 1/64th for a 1000mm.

For the same production Hurlbut required unusually strong neutral-density filters. While other types of filter may have become less popular in the digital age, the need for high-quality ND filters has only increased as cameras have become more sensitive.

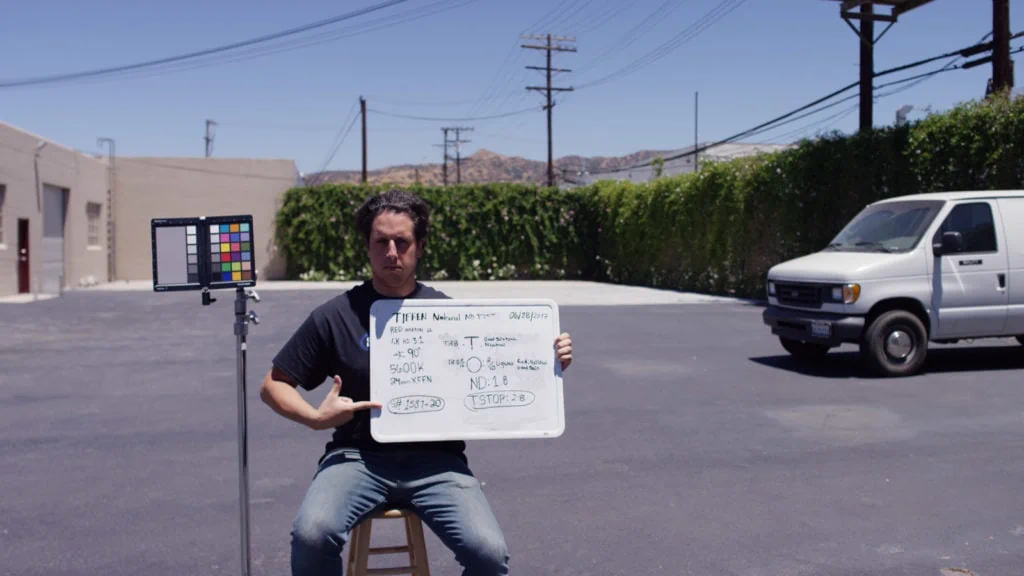

Hurlbut wanted to shoot sunny day exteriors with a large aperture of T2 and a high ISO of 3200, meaning a huge amount of light needed to be cut before it reached the sensor, as much as 14 stops’ worth. He turned to Steven Tiffen to develop a new filter series, the NATural NDs, which would hold their colour consistency and stop accuracy even when multiple filters were stacked.

Enlisting colourist Michael Cioni at Light Iron to help evaluate the results, Hurlbut shot a series of tests with the filters as they evolved over a two-year period. “We would set [the tests] up so we were shooting at high noon so we had the most IR pollution possible,” notes the DP, referring to infra-red light which causes some cameras’ images to skew magenta under strong ND filtration if not specifically blocked by the filter.

He was extremely pleased with the end result. “It does something with skin,” Hurlbut remarks. “It brings out a vitality, especially across darker skin-tones.”

Kate Reid BSC has a different filter in her arsenal when it comes to making faces look good: a polariser. These work by cutting light travelling in a single plane, typically reflections or specular highlights.

“I often use a pola filter as part of my standard drama set-up,” says Reid. “It is a useful and fast way of controlling a highlight on an actor’s face; either augmenting an existing highlight if that is desired or reducing it to matt the skin.” She adds that close collaboration with the make-up department is important to ensure that the filter is not working against their creative intentions.

Reid also likes to use diffusion filters. “Diffusion in front of the lens organically interacts with the light in a way it can’t when it’s added in a grade. And wherever possible l would prefer to commit to a look and create that in camera rather than it falling to the mercy of post where that may be overruled or become an additional cost.”

Reid’s television work includes episodes of crime drama Marcella, on which she used Tiffen Glimmerglass – “just 1/8th or 1/4 depending on the lens; enough to give a flattering glow to the lead actress’s skin but not so obvious that it detracted from the noir feel of the series” – and period sci-fi The Nevers, for which she primarily relied on Black Diffusion/FX “which maintained a subtle diffusion without reducing contrast in the image”.

For HBO’s upcoming dark comedy series The Baby, Reid wanted filtration that would counter the sharp 6K resolution of the Sony Venice. She selected Tiffen’s Soft/FX, which contain an irregular pattern of oval lenslets. “They give a gentle overall diffusion which doesn’t impact highlights or shadows greatly when using a lighter density.

“I like being able to subtly differentiate spaces or periods of time within a story visually,” Reid reflects, “perhaps born out of film-school days where I would only have one set of lenses on a project and playing with filters was and can be an economical way to create quite a different look from the same set of glass.”

Filters remain an important technical and creative tool, helping cinematographers expressively enhance stories, be it with acid-etched moon shapes, oval lenslets, cracked glass or nose grease!