WORLD UNITED

Find out how some productions are combining visual effects flair and natural history expertise to create the next generation of wildlife documentaries.

In 1999, Tim Haines, BBC Studios Science Unit, Discovery Channel, and Framestore released an ambitious six-part nature documentary television miniseries, Walking with Dinosaurs, that mixed real locations with CGI to give audiences an idea of what it was like when the extinct creatures roamed the Earth. Fast forward to 2024 where CGI has become photorealistic and the streaming services have emerged as the dominant viewing platform. Apple, the BBC Natural History Unit, David Attenborough, and MPC collaborated to create Prehistoric Planet, while Netflix went about producing Life on Our Planet with the help of Silverback Films, Morgan Freeman and ILM.

Both Prehistoric Planet and Life on Our Planet rely upon combining the expertise of Oscar-winning visual effects companies and renowned natural history cinematographers to turn fossils into living and breathing creatures; this hybrid approach has provided an opportunity to expand the visual language. “The value of a natural history background in the director is important because it’s telling stories about animal behaviour,” notes David Baillie, whose career includes shooting aerials for Prehistoric Planet 2. “But because we have actors that we can control, let’s use all of the techniques of drama filming to tell this story rather than being hung up on trying to shoot it as if we’re a natural history crew.”

Framing was not entirely left up to the imagination. “The close shots [in the “Oceans” episode of Prehistoric Planet 2] were quite interesting because they couldn’t break the ice, so we had a hovercraft bring in a 3D printed head,” reveals Baillie. “I framed up, we took the hovercraft and head out, and then I did the shot. By then I had got it fixed so I knew where it would be.”

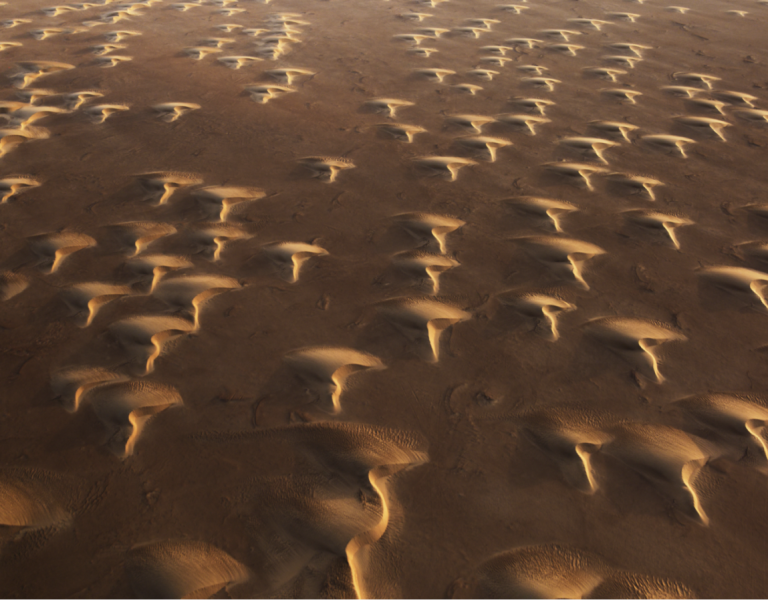

The shooting schedule was short and precise, which was something Jamie McPherson had to deal with as the visual effects director of photography for Life on Our Planet. “The main thing about filming natural history is you’ve got a month to film tigers so you’ve got all of those dawns and days, while on a visual effects shoot, you might have four or five days to make that valley in Arizona look as good as it would have done if we were filming it over a month.”

McPherson pioneered taking a Cineflex GSS from a helicopter and attaching it to a vehicle to do tracking shots for the BBC series The Hunt. “It was the first time anyone had ever been alongside wild dogs at 40 miles per hour through Zambia and I was brought onto Life on Our Planet to give the Raptor sequence that same sense of movement and style. You’re going to follow the creatures and find places where you’re alongside them but not right in their faces. We used the same GSS and a Canon 50-1000mm lens to compress it. We felt that would let it sit alongside the natural history scenes in the most seamless way.”

The favoured camera was the RED Monstro to produce 8K images that the animators could reframe if needed. “The Fuji full-frame Premista zooms were great lenses for that purpose, as were the Zeiss eXtended Data Primes,” states Paul Stewart who is a writer, cinematographer and producer on Prehistoric Planet. “Honestly, there was never one big challenge, just a series of everyday, mundane ones like how do we afford the kit we need, how does the shoot go ahead if someone gets COVID-19 before we leave, and why isn’t the camera working? In the field the problem was often having animals appear we just didn’t want. While filming in Zambia for the Prehistoric Madagascar segment of the “Islands” episode in series two, we often found ourselves flanked by both lions and elephants. They were disconcerting ‘extras’, and hard things to hide in a background!”

–

Words: Trevor Hogg