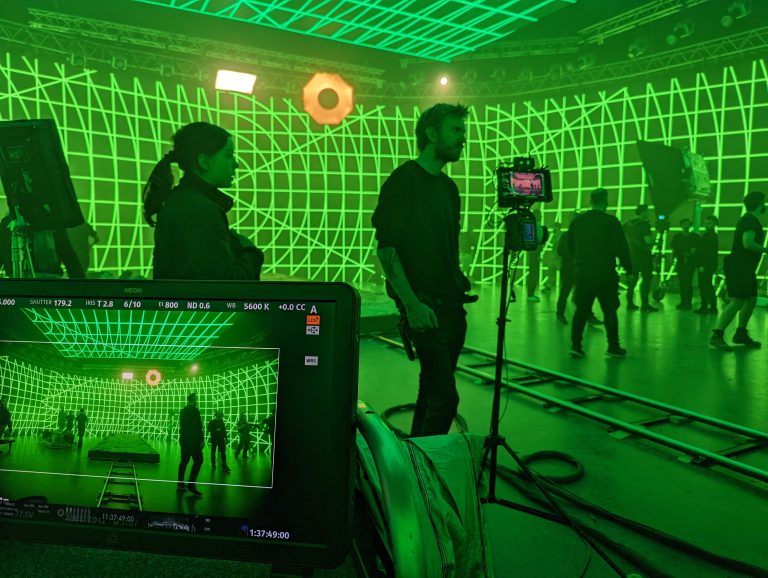

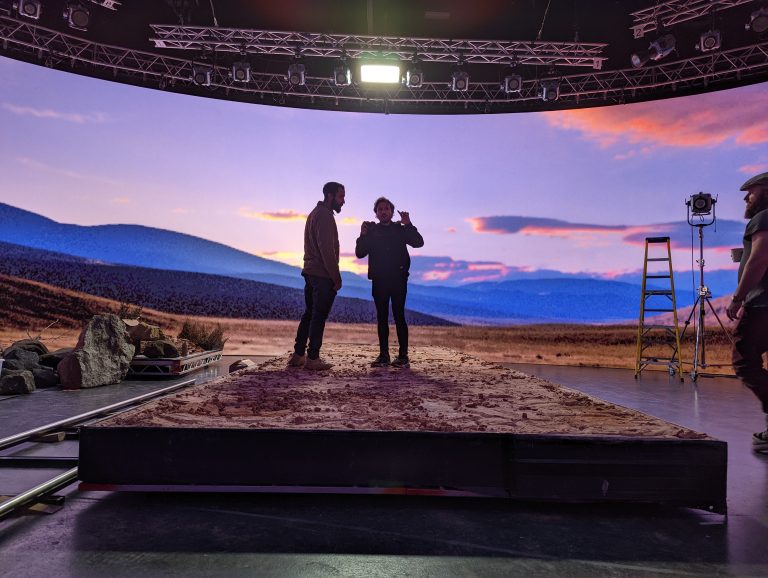

A director/DP and a VFX supervisor share their insight into selecting the perfect lens for a volume shoot.

Relationships between camera crews and effects people have sometimes been strained by the occasionally contrary demands of the two disciplines. If there’s been a prominent upheaval in that world recently, it’s virtual production (VP). There are many benefits, perhaps chiefly reduced restrictions on the camera department.

Director/DP Brett Danton’s experience in VP prompts him to begin with a note of caution: “It depends on what your final product is. If you’re shooting on a virtual wall and that’s your finished frame, great. But if you also have a motion control robot on it, and you’re extending the scene out [with conventional VFX] then you’re probably best using conventional lenses without too much distortion.”

When the virtual world won’t be augmented with conventional VFX, though, options open up, as Danton confirms. “I use the Canon Sumire lenses quite a bit with virtual production… they have a little bit of a bleed in the highlights. I find the images wraps around a little more, it embeds the subject into the lighting a bit more. But on a job last week we couldn’t do that because we were extending our scenes.”

As with any new technique, Danton says, tests are key. “If you can get on there beforehand, try to do a camera test day with your lens and camera package. You don’t need to shoot much, just evaluate that moiré.” Another reasonably recent innovation which Danton finds useful is full-frame cameras, for their reduced depth of field. “Super-35 can be a bit of a fight on a volume stage… I did a whole lot of camera tests [where] we ran a lot of cameras to work out which was the best on the moiré. On a smaller volume stage, if you’re on full frame and you’re relatively wide open, [full frame cameras] can allow the subject to get back a bit more, and you don’t need as big a screen.”

VP supervisor Asa Bailey, founder of VP company On-Set Facilities, echoes Danton’s enthusiasm for characterful lenses. “In a way you’re helped by a more, shall we say, vintage look. They respond less to the LED wall… it sort of compensates for the fact that you’re shooting millions of dots. […] It becomes more of a choice then. You can shoot sharp or go for this more aesthetic feel.”

VP is often reliant on electronic encoding of lens settings, although, as Bailey confirms, that need not be a barrier to using a favourite piece of historic equipment. “You’ve got to be able to take the lens intrinsics and get them into the engine, so the virtual world is in sync with the optical world. With modern lenses you’ve got the lens data, it’s encoded. If you bring out a vintage lens, some Russian glass, you’ve then got to go to being able to put gears on the lens and accurately encode that data via a physical gear. Doing it via gears, I can mount any lens on any camera and get it to work for virtual production.

“Then it comes to the ease of how you can encode a lens. Anamorphics take the longest – we require a day to do the encoding on [them]. A spherical lens we can get encoded within an hour as long as we’ve got it on set.”

As the technology becomes more common, and frankly less expensive, its democratisation seems almost inevitable. “This technology is now accessible to the whole gamut of media production and content production,” as Bailey puts it. “That’s where these industries don’t get so much time or R&D and the training or setting up of these things. But if you take a fully expert crew like ours we can turn up on a day and do it in a quick turnaround. DPs… shouldn’t have to deal with that.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes