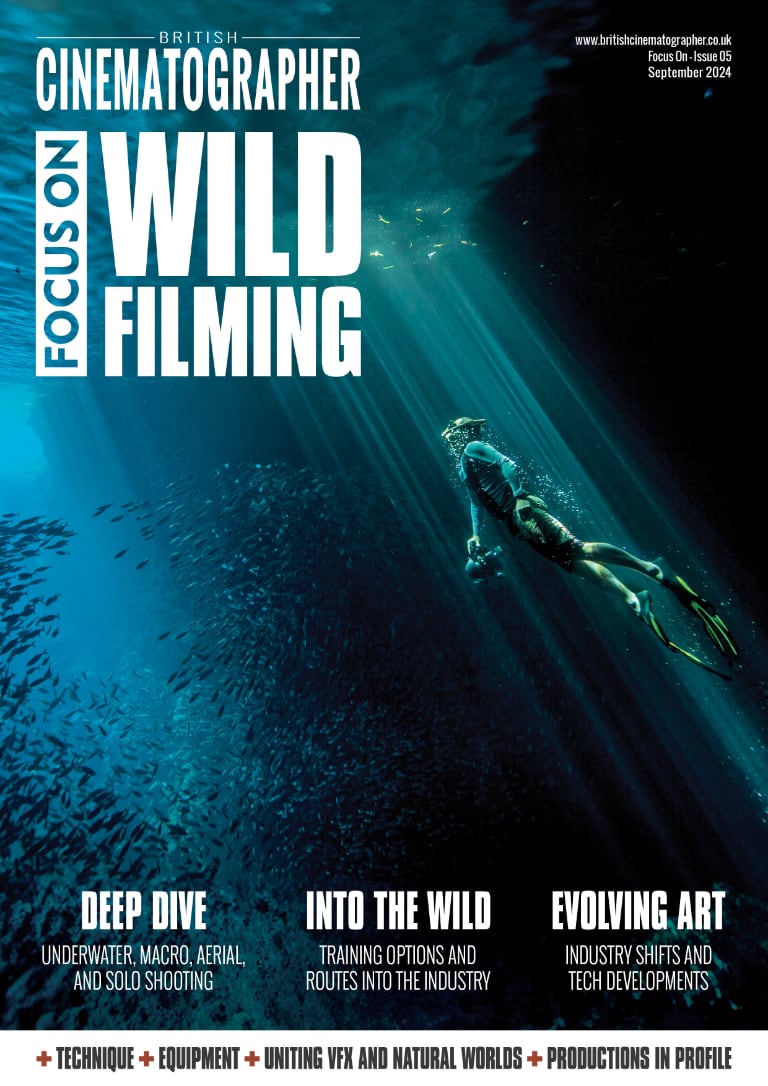

INTO THE BLUE

Join the cinematographers taking the plunge into our oceans as they strive to capture the world beneath the waves.

It used to be that simply taking a camera to an unusual place – the top of a mountain, space, or the depths of the sea – would satisfy producers of high-end documentaries. Now, the phrase “blue chip” refers to natural history work which demands much glossier results, and it’s hard to imagine a tougher place to maintain that standard than underwater.

Like many people in this line of work, Abraham Joffe ACS was a diver before he became involved in documentaries such as Tales by Light, Big Cat Tales and Ghosts of the Arctic. “I think my first dive on the (Great) Barrier Reef was when I was ten years old. Australia is a fantastic place to learn to dive… Like any filmmaking, you get so engrossed in what you’re doing and your head is in the viewfinder, the diving and the safety aspect has to be second nature.”

Those rising creative demands, Joffe says, demand better equipment. “There used to be underwater camerawork which was locked off on a tripod, but more often a housing carried by a diver. What’s changed over the last decade is that [we use] almost any tool that’s used in production… motion control tracks, underwater dollies, time lapse, elaborate lighting setups, and of course a huge variety of lenses. The visual look has changed hugely and it gives people all those tools to tell a story below as much as above the surface.”

Underwater documentaries can be, Joffe says, very unlike recreational diving. “You can dive on air, which covers a lot of [how] the underwater work is done, on scuba. But a rebreather is such a game-changer – so much of the Blue Planet and those top underwater series use rebreathers because there isn’t an exhale of bubbles. Bubbles underwater usually signal predator, but it’s a very technical way of diving and fraught with more risks than scuba.”

Joffe deeply respects underwater filmmakers who demonstrate exceptional skill without relying on breathing gear. He notes that in specific locations, such as when capturing Humpback whales in Tonga, SCUBA is generally prohibited. This requires filmmakers to possess significant freediving expertise to achieve top-quality underwater footage. “With things like whales and other mammals, if you’ve got to be jumping in and out of the boat following things, having the huge system isn’t good. The best underwater crew are all freedivers.”

Breathtaking work

Gail Jenkinson’s thirty years’ experience includes work on Blue Planet II, Earth’s Wildest Waters, and experience freediving on Patrick and the Whale, which she describes as “about a man and a sperm whale and their interaction. The regulations in Dominica say you’re not allowed to film the whales with scuba gear, so, that meant holding your breath. It was one of the first jobs I did like that and I really enjoyed it.”

Happily, as Jenkinson goes on, “you can train on land… you can increase your breath hold so that when you are in the water, after all the logistics of leaping off a boat, swimming fast at the surface, being in a position where the whale may come and be in the right place, you can calm yourself down, hold your breath, focus, frame up and press record.”

Doing that day after day for weeks or months, Jenkinson says, is “tough. People will try to bring in a day off, which we’re grateful for, but it’ll always be the day that the weather’s good… you could have weeks of lying in a cabin below deck waiting for weather. You’ve got to manage that time, then when the good weather happens you’ll go out all guns blazing.”

While light weight might therefore seem a boon, Jenkinson is cautious. “When cameras become too small they become very twitchy in the water. With the sperm whales I used a Gates Pro Action housing which is quite hefty… you’re going to fight a bit harder pushing it through the water but when you’re on a shot it’s going to give you stability, and I value that over a smaller, lighter object every time.”

Cold comfort

It’s tempting to think of natural history as a place of perpetual sunshine and tropical waters. Kjetil Astrup SOC’s experience, however, includes Wild Scandinavia and Frozen Planet II – though his ambitions were founded in warmer climes. “I always knew I wanted to be a cameraman. I was doing my PADI open water licence, going to the Red Sea and having fun. I saw these people on a boat filming dolphins, whale sharks, stuff like that. A year later I moved to the Red Sea and started filming in the water.”

Astrup’s career has involved both drama and documentary. “I think I get more jobs because I put the cinematography into the wildlife stuff. Especially on blue chip documentaries, you need to know your exposure well, steadiness in extreme conditions, to open up your lens a little bit more than usual because you want shallow depth of field. In wildlife, a lot of it is very, very sharp, but in some documentaries you’d want a bit more of a cinematic feel to the visuals.”

Achieving that feel has many of the same considerations as any other production, although Astrup points out that underwater work can push filmmakers away from the commonest choices. “We build up from the minimum requirements they have for post. Is it for Netflix? Do we need it in 4K? Many times we’re shooing on RED, but in Norway we’re often shooting on Sony A7S III, which still delivers 4K, but the ISO on this tiny camera goes to 12,800.”

Natalie Turner-Blackman echoes Astrup’s thoughts. “Our primary underwater cinema cameras are always RED on natural history units. We use RED Raptor at the moment. That’s the main camera on the series I’m [currently] working on. Then for smaller rigs, we tend to use Sony cameras. The A7S III is a workhorse.”

Turner-Blackman began as a technician working on exactly the kind of bespoke engineering that documentaries increasingly demand – “polecams, underwater timelapse sliders. It gave me such a range of technical knowledge. From that I was really lucky to get on a production called Prehistoric Planet. It was really interesting, a different kind of natural history shooting, VFX orientated.”

Much as complex setups for natural history documentary may be recreated on stages, advanced underwater work may use tanks, as Turner-Blackman relates, “to replicate things that aren’t possible in the wild. Specific timelapses, a macro creature, or something that’s quite tricky to manage in the field. Prehistoric Planet was interesting technically in how it was shot… we had witness cameras and dual triggers all underwater. It wasn’t like your usually natural history stuff – shooting plates waiting for animals to leave shot rather than enter.”

Sometimes, though, concerns are simpler. Turner-Blackman recalls a shoot involving gannets tempted to dive for bait. “We were in the North Sea and had chum for the gannets, to get them enticed… there were thousands of them swirling around us in the sky. It was amazing to see them plummeting down into the water. We did consider using helmets at one point – ‘if they come down onto our heads we’re going to get impaled.’ But they have pretty good aim. We’re not very interesting!”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes