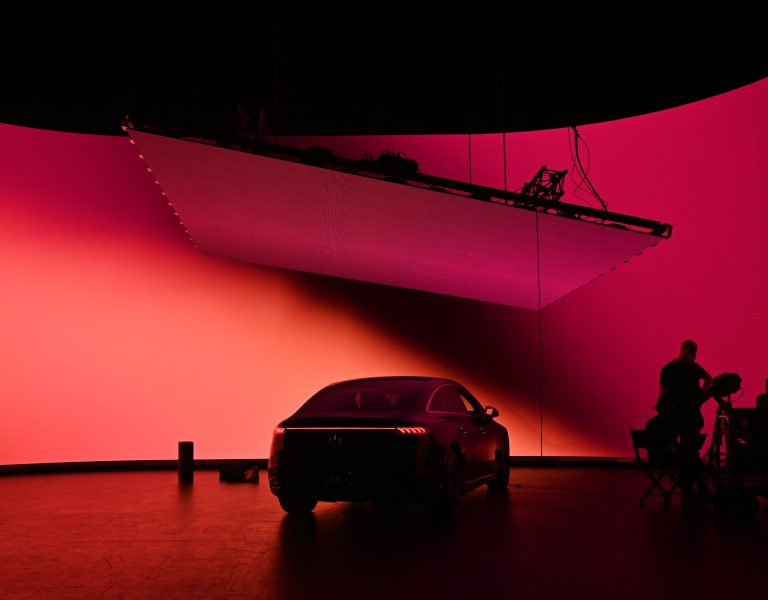

As ever more virtual production studios open their doors, filmmakers are spoiled for choice by the facilities available in the UK and beyond. But narrowing down the perfect stage for your requirements can be tricky.

Lots of people will expect to stroll into a virtual production studio and see a giant LED videowall and camera tracking equipment. Perhaps there’ll be a humming server room somewhere set up to generate 3D imagery for the wall, and some people at workstations in the studio ready to conduct the resulting orchestra of technology. That expectation will be right at least some of the time, though it’s a field in which details matter, prep is key, and not every facility has exactly the same capabilities.

Sometimes that’s true even of two stages run by the same company. Sarah Thomas Moffat is a cinematographer working between London, Los Angeles and Canada who found out early that different facilities are likely to offer different things. “In 2022 I stopped by ARRI’s Uxbridge location and their massive stage. That was exciting, and then literally a month later, in June, I went to LA on my motorcycle from Vancouver, where ARRI were just building their creative space. It’s a smaller studio, it’s a test studio. I said, ‘I need to bring my motorcycle in here’, they were like ‘OK, we have to test out some Unreal Engine assets.’ So, I went in with my bike, lit it, and ended up making a little demo video which ARRI actually used in their web page.”

Serendipity aside, Moffat’s exploration of facilities on both sides of the Atlantic revealed a huge variation in both intent and implementation. “The SMPTE did a VP showcase in London earlier this year, and they repeated it in Los Angeles. I worked on that with the UK team; it’s starting to grow in Toronto, there’s a few in Vancouver, Hollywood has massive numbers of facilities. I really see the difference in what people are offering and what they consider to be a VP facility. There are some pretty wild ones. I visited one which professed they were a VP stage – it looks like VP on the website – and it’s literally a green cyc, and they have a keyed in image on the monitor on the camera. It’s not an LED volume.”

Moffat’s approach to heading off trouble when approaching new facilities is simple: “I have a checklist. I had worked with ARRI originally, and ARRI was mapped and tracked, and the lens was tracked. That was my introduction to the standard which was the top of the game. I thought every studio did that, and I’ve learned to ask because they don’t. Some walls are curved, some are flat. How big is the wall, how much space do you have? What are your lens needs, what are your shot needs, the distance of the wall and camera to the subject? How big is the studio, is it a small rectangle or a big studio where you can back the camera up, so you’re not stacking [the subject] close to the wall where you have moiré issues?”

The reputation of virtual production as a convenient way to operate can be at risk, Moffat warns, where certain facilities lack what certain projects need, and that’s not necessarily down to either the facility or the production but a combination of both. “There’s a trust factor that influences the producers to spend the money on it. Say their needs were a fashion shoot or a simple music video. They just need a backdrop. You can do a bunch of pictures on the backdrop in one day, but if you’re getting into TV productions like Mandalorian or creating scenes as we did for SMPTE, you need a sophisticated studio, plus the production team on the virtual art department side to create the assets and work with the production designer. Most people are willing to help get you there – they want the studio to look good, they don’t want to build a bad reputation for the studio.”

Cinematographer Paul Mortlock has been involved in film and television production for over two decades, and still considers virtual production to have “a pretty fast learning curve [but] the technicians are very generous with their time. You can go in and spend some time to see how it works. That’s how my journey began – I shot a worldwide Lego commercial on a stage in London.”

The commonest problems are those which could affect any VP facility which uses camera tracking. “I guess the common problems are moiré, camera tracking, jumping backgrounds, ghosts in the machine of Unreal,” Mortlock reports. “But stepping back from that, working with different volumes, you find they react differently with different cameras. Some cameras you’ll get more moiré, and others you get away with it. It could be just changing the position of the camera, changing where the focus sits, changing lenses – finding a way you can clear these problems. Of course, nobody wants to be faced with that on the day, but those sort of problems aren’t going to be a surprise if you test.”

Tracking might rely on any of several different systems, all quite valid but using different principles and therefore experiencing different issues. “There’s quite a few different systems out there,” Mortlock points out. “Problems are badly positioned emitters, or someone’s rigged something in the way of it, or we haven’t got the greatest view… one issue we did have was when putting twenty-by-twenty silk up, and the system was not enjoying moving from the markers on the ceiling to the markers we’d put on the silk. That’s just an anecdotal problem which was very easily solved, but I’ve had issues on set where we’ve had problems with it all day – we’ve moved the emitters, tried cables, and it turned out it was one slightly dodgy input to a computer.”

Mortlock’s advice is relevant to both the facility’s people and members of the camera department who might interact with them, and it’s simple: “If there’s a problem, communicate it clearly first, with me, with whoever needs to know, that this is going to have a time constraint. Now we’ve all been doing it for a while, it’s fairly obvious when things aren’t right. Get that comms to the people who need to know. The studios I’ve worked with have it all sorted out, but it stops the frustrations of people not knowing what’s going on.”

The variable stack of technology involved in virtual production means that fine adjustments to lighting and screen configuration are inevitably done by eye, specific to every combination of production and facility. “I match everything by eye on set,” Mortlock confirms. “We’ll get as close as we can to the numbers, the colours, the light drop off, the way it’s falling. And extremely good midground art is crucial – anything you can do to help bring the two worlds together. At first people were thinking you just throw a person in front of a screen, but that art is very important to trick the eye. Take any excuse to be able to put in some lens flare or a strong backlight, even a bit of haze. That’s what helps tie the world together.”

In the end, the success of the production is also the success of the studio. Mortlock puts it straightforwardly: “They know it’s technology that they need to sell, to explain, and everyone needs to understand it. They’re doing great at all those things – offering time to come into the studio and test or just to come in and understand. They’ll all do that. It’s in their best interests to do so. I think they’re doing brilliantly to be honest. All the studios I’ve met are good at giving you that extra time to hone stuff in.”

There’s some comfort to be had in the fact that the studios seem to very aware of the concerns of camera crews, particularly where the people behind the facilities have cross-discipline experience. Nathan Newman is co-founder at Pathway XR in Manchester, with over 20 years’ background in media and technology. Newman’s first ten years, he says, were “focused on the art and creative side of the video games industry. I worked on something like seven or eight game titles, some of them published by the likes of Midway, Activision Blizzard, Sony Online Entertainment and Warner Bros. Then, in the second ten years, I worked across advertising, marketing, and tech startups, and also some independent film pieces. I’ve directed TV ads, so I was familiar with how to shoot, what DPs and clients need.”

Newman describes the studio as having worked on “around twenty-five projects in the last year, which have all been VP related. From that I can understand how different people are approaching the technology, what was working and what wasn’t. For each of those projects we approached them as a learning process, with a feedback process where we’d feed the learning from each shoot back into the next.” Given a broad slate of productions and their varying demands, it’s tempting, Newman says, to sell a facility as suitable for anything. “There’s an element of uncertainty that’s solved in the sales process when [some facilities] say ‘we have everything here you could possibly need!’, but the truth of the matter is how different shows and DPs have different requirements and different styles.”

Handling that situation, Newman says, is less about technology, and more about technique. “We get people on a stage sooner, before a job even starts, to try out ideas. A lot of studios have their LED panels in flight cases. We always have ours up, trying out new things. The first studio that we have here in Manchester we position as three things. The first is an about innovation, the second is an art space and third is a production space for VP. Our innovation rate card is far less than our production rate card and that’s specifically to foster innovation and to challenge these barriers people might face around trying something new.”

Newman’s closing thought returns to his background in video games, where there are perhaps more formal processes available to discuss the risks created by the collection of technologies and ideas that different virtual production studios might offer. “These productions are so technical that if you’re not aware of problems early on, people can make decisions which create these technical or artistic debts. Sometimes those decisions are being made before engaging with a studio, and when they do engage, you find it’s a bit touchy as an early-stage project doesn’t want to share information. Before we even go into production and before that film is financed, we liked to get ahead of everything. That’s perhaps when people want to try new things, rather than just recreate location shoots. That’s the mentality – get in early, and test.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes