GREEN VENOM

The Essex Serpent sheds its carbon footprint, embracing sustainable practices and green innovations for environmentally friendly filmmaking.

The Essex Serpent features a lot of the natural world. Based on Sarah Perry’s novel of the same name, much of the story takes place on the coast of East Anglia, a location offering environmentally sensitive salt marshes with spectacular views but few ways of powering upscale filmmaking equipment. Cinematographer David Raedeker BSC took full advantage of technologies that made things both easier and greener.

The production shot on location for eight of its 20-week schedule. “We mainly used batteries,” Raedeker recalls. “We mainly had very low-powered LEDs. We only very occasionally, once or twice, used HMIs, but creatively there wasn’t really a problem. We shot it on an Alexa Mini, and I would do 800 ASA, maybe night stuff at 1600. We lit it, even exterior nights, with Creamsource Vortexes and Astera tubes. It’s much faster so you need less crew. We had a Technocrane, and we ran that from a 5kW battery.”

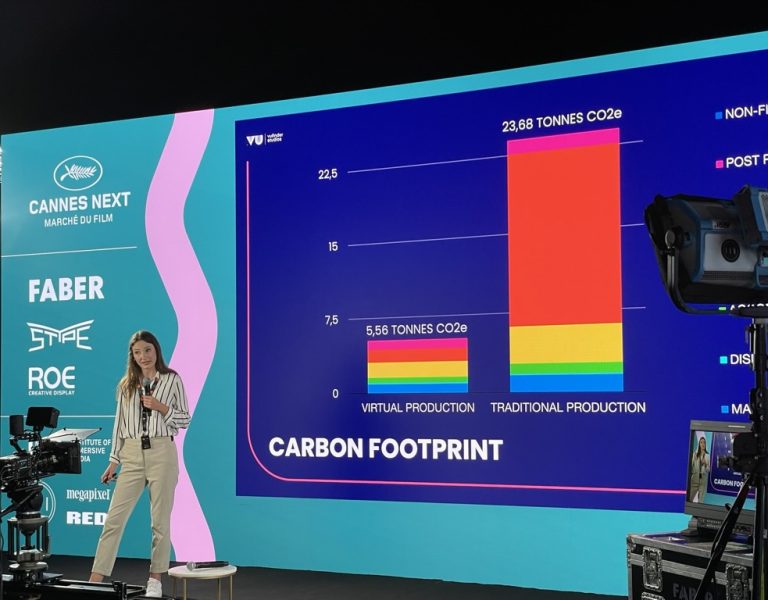

That reduction in crew is an indirect vector for reduced carbon emissions. “The big thing is that travel and transport is 55%,” Raedeker points out. “That’s 350 tonnes of CO2 in travel and transport. Yes, we always have to travel, but there could be more approaches to more support for electric vehicles, charging points—all of this infrastructure could be made easier. We can all talk about recycling on film sets for the rest of our lives but… the elephant in the room is transport.”

Raedeker reflects, meanwhile, that his positive experience on The Essex Serpent is far from universal. “Essex Serpent had really good people on it. They really tried.” If there’s a single key to meaningful change in the wider industry, he suggests, it’s “power solutions—the connection between locations, lighting, everyone who needs power. If that is better organised and can run with hybrid generators and mains power, that could lead the way to electrification to supply cars in the end.”

Harriet Lawrence was the production’s supervising location manager and very much involved in the sort of interdepartmental cooperation that Raedeker proposes. “I won the Screen International award for use of locations in a TV series, and a lot of the background to that was about working on the salt marsh.” It is, she says, a delicate environment. “They’re irreparable and they’re degenerating once we walk all over them. For an actor running across the salt marsh, the only footprint was the actor. We could follow with the drone.”

Promisingly, power supply is also high on Lawrence’s list of considerations. “Smaller, more mobile, towable generators have always worked well for us because we can move them wherever the trucks are needed, which is why the OnBio Orb and Green Voltage work so well.” Battery-powered mains supplies inevitably need charging, but “we didn’t need to, much. Yes, there’s a point where you do have to charge them on diesel generators but… running a diesel generator for two hours will put a majority of the charge back in”.

Bringing those ideas to the industry in general, Lawrence concurs, might be facilitated by better planning. “The better the planning, the greener we can be. A lack of planning impacts on every level, from everyone’s sanity and mental health to the budget… there’s a tendency to overspec everything. When I was involved in writing the guidelines during Covid, we thought the one good thing that would come out of it was that everyone would plan better.”

For many reasons, that wasn’t quite what happened, but Lawrence suggests the principle is sound. “The better we plan, the more efficient we are.” In the end, Lawrence echoes Raedeker’s conclusions: “We’re not at the point where being green costs the same as not being green, and until that happens, you need the support of whoever’s commissioning it.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes

Comment / David Raedeker BSC / member of the BSC sustainability committee