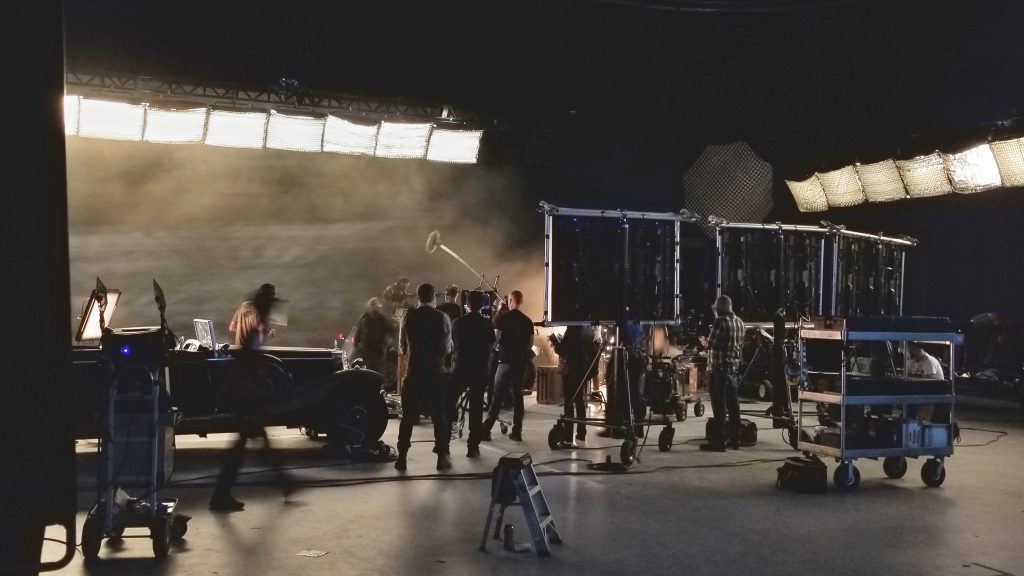

The question of whether a virtual production stage’s videowall counts as a lighting device is still vexed, even as the technique in general becomes a comfortable part of the mainstream.

One of the people who is perhaps best placed to address the issue of lighting for virtual production is Markus Förderer ASC BVK, cinematographer on Red Notice, The Colony, Bliss, and Independence Day: Resurgence, whose background with the technique goes back almost as far as the technique itself.

Förderer’s introduction is frank. “On almost every project I used some form of virtual production – bigger walls, smaller walls. I have a love-hate relationship with it. I always push for it, but I totally know the constraints.” As a lighting device, the shortcomings of every wall to date are clear: “The colour quality, most of the time, looks like a fancy computer game no matter how much money you throw at it. The light coming from [simulated environments] is not realistic. That’s why I’m always pushing to shoot panoramic stills, to start with something photoreal. Then the background of the wall is something photoreal and the starting point of the colour is real to the eye.”

“Then you’re dealing with the issue of red, green and blue pixels trying to mix colour,” Förderer reflects. “The breakthrough for LED lighting was when they added the white pixel, blending the spectrum to something that looks natural.”

Cutting-edge virtual production stages might even offer the option to control LED production lighting using data from the video signal itself, though Förderer prefers to ensure consistent lighting conditions by using consistent equipment. “There are ways to connect your lights to the wall content to pixel-map the light, so the animation matches. But if you pixel-map the colour, the film lights can react very differently to the wall. I’ve seen the Kino Flo pixel mapped lights. I’ve tested the Sumolight Sumosky, which is an interesting idea, but there’s no general trick that solves it all. I try to rely on the light of the wall or have smaller portable sections [of the videowall] as a light source.”

That light source, Förderer goes on, might be modified using a variety of conventional techniques. “I might use large silver bounces like on a twenty-by-twenty frame, put a silver textile in it and reflect back the wall light, so it’s always the same colour and animation. Then, even if the colour quality is not as good, it’s kind of balanced, then we can tweak it with in camera colour control.”

Because cameras and eyes might see the same light differently, Förderer makes his final adjustments on a monitor. “Sometimes I’ll put a floppy behind the monitor, so I don’t even see the set, then balance to what I see on the monitor.”

The reputation of virtual production as a high-end technology with a high-end price tag is gradually being dispelled, as Förderer reflects, by the growth of facilities targeted at simpler jobs. “I’m glad to see smaller walls popping up. It’s such an expensive technology [that] it’s often prohibitive for many producers to use virtual production. It becomes such a beast financially that they’ll say, ‘we’ll figure out another way to shoot that sequence.’ But you don’t always need camera tracking and parallax.”

For Förderer, in the end, the lighting implications of virtual production are a large part of their appeal. “The big breakthrough in visual effects, for Jurassic Park, when things started looking photoreal, was when they started using the silver spheres to capture the environment and use it on a CG subject. If you put this natural environment there, it suddenly looks real. The revolutionary moment was to bring that sphere back on set. Instead of a green cave we have a cave that represents the real environment and real lights and, to me, that’s 90 percent of the magic of virtual production.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes