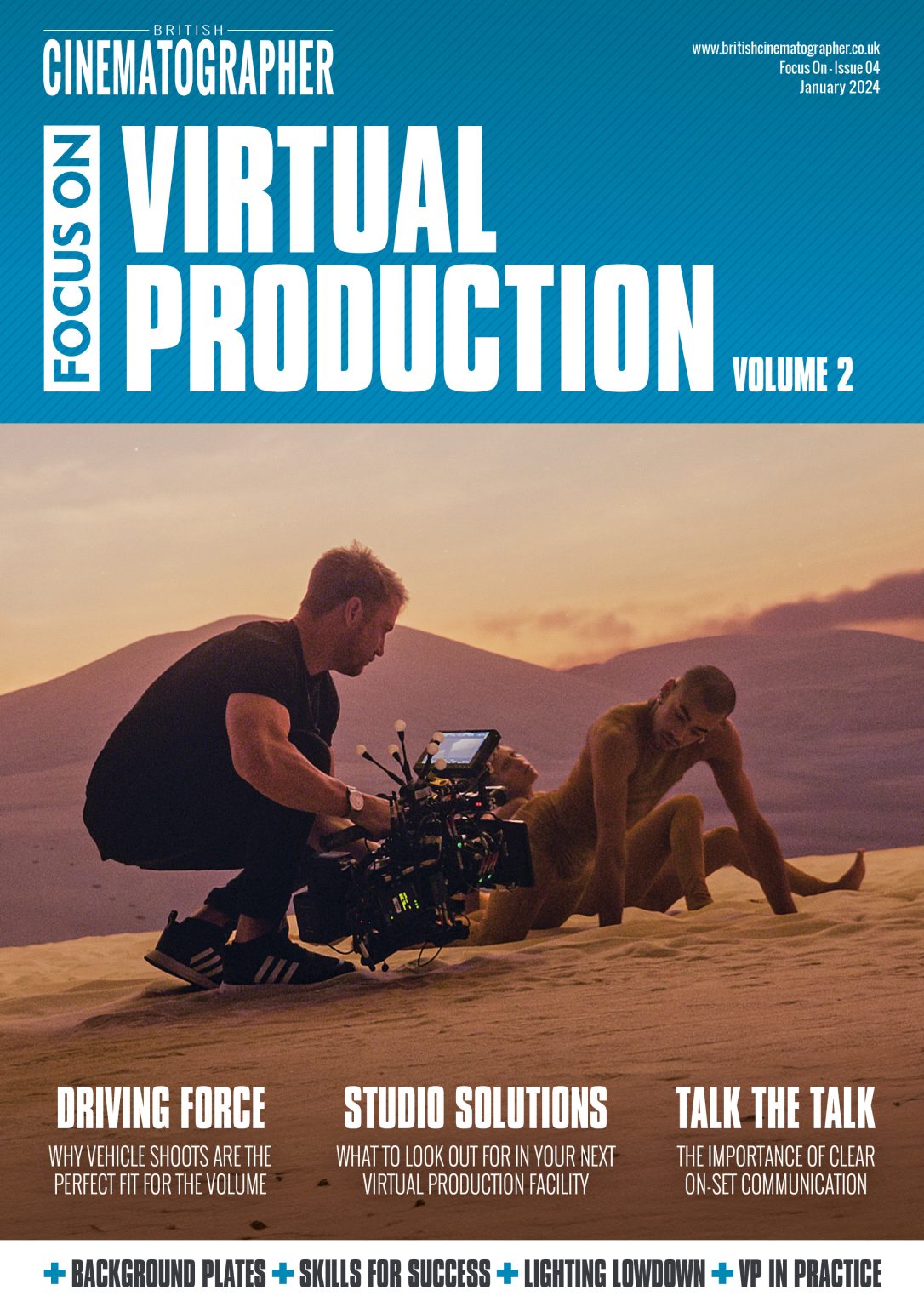

Exploring the vast expanse of a desert for a music video holds undeniable allure, but virtual production means braving the elements was no longer a fear, as David Procter BSC explains.

The allure of sweeping dunes, stark beauty and endless vistas offers an ethereal quality that seamlessly harmonises with music. However, this appeal accompanies a set of challenges, primarily arising from the unpredictable nature of weather conditions that can disrupt even the most meticulously designed plans.

Through skilful utilisation of virtual environments and augmented reality, artists and filmmakers have gained the ability to meticulously reconstruct the captivating essence of the landscape, all from the controlled environment of their studio.

Ellie Goulding has added her name to the list of artists who have been captivated by the desert, choosing the arid landscape as the backdrop for her single, “Like A Saviour”.

If you haven’t seen the video yet, it showcases the singer accompanied by a group of backup dancers, all immersed in the vast expanse of sand and sky. The scenes seamlessly transition between the captivating beauty of both daytime and nighttime skies. Within this seemingly inhospitable environment, Goulding and her interpretive dancers appear stranded, with each member moving with a distinct purpose, functioning as a united ensemble.

The brainchild of director Joe Connor, the concept hinged on creating a landscape where passage of time, light, weather, and the horizon could be manipulated. To make this a reality, the DNEG and Dimension team created a five-square-kilometre desert landscape in Unreal Engine, complete with a live AI weather system and cloud rendering.

“We designed a sun path that allowed us to manipulate the passage of time with a 24-hour cycle lasting around two minutes,” explains David Procter BSC. “The goal was a hybrid timelapse of light movement, yet without frenetic clouds, which instead moved in real time. The result feels familiar, yet otherworldly.”

Procter explains how the “creative challenge” was to light the set in a way that felt naturally motivated yet preserve the ability to shift our sun angle and ambience to match the timelapse aesthetic – from dawn to dusk and into the night.

“Due to restricted ceiling height we opted to rig Ultra-Bounce above the volume, acting as a passive sky,” he explains. “We supplemented this with Robe Forte and ClayPaky Unico moving heads bounced from the ground that could move and animate, enhancing the complexity of light, as if rendered by an organic sky.”

The team opted for Nanlux Evoke 1200B units as back lights, which ran without lenses as this gave the broadest spread of light across the set. A Nanlux Dyno1200C rigged into an additional 20×12 Ultra-Bounce acted as a frontal key when required. An additional Evoke 1200B was used with an Octodome where a more localised beauty light was required, or acting as catchlight in wider frames. The team then lined the circumference of the volume with LED Colour Force battens which helped wrap around the directional light. All lamps were controlled via DMX by desk operator Frankie Shields.

“Joe wanted flexibility in our environment, sun path, time of day and transition length, so we didn’t pre-programme frame accurate lighting sequences,” Procter explains. “We instead pre-programmed 12 lighting states and transitioned live between them, including dimming, colour shift and light direction. We paired Frankie with post-vis supervisor Jesse Baber who was able to give cues, just seconds ahead of shifts.”

Whilst with time, the whole lighting design could have been pixel mapped, this organic approach allowed for spontaneity and ‘happy accidents’, which, Procter says, is often when magic happens in filmmaking. “I feel that lighting with a cocktail of textured, animated light and LED screens gives the light and reflections in skin tone a complexity reminiscent of a real-world environment,” he adds.

With the backdrop firmly in place, Procter and his team had to ensure the virtual sand and other desert elements interacted realistically with characters in the video. Production designer Oliver Hogan devised a circular deck set back from the screens and raised to avoid seeing the gap between real-world and 3D. Procter says that checking this optically with a 3D pre-vis was invaluable. “Sand colour was carefully deliberated and to help with integration we opted for some foreground contouring that could be added for variety in landscape,” he explains. “Colour integration was done carefully during our pre-light by both manipulating on-set and 3D lighting. Using real sand was integral in giving Ellie and the dancers something tactile to interact with. For me, the most successful examples of VP are when as much foreground set [as possible] is built practically.”

Then, of course, comes the process of integrating live-action footage with the virtual desert environment for seamless blending. Procter says authentic integration of foreground and environment “is a delicate balancing act” reliant on meticulous collaboration.

The goal was to achieve a grounded aesthetic that feels tactile and organic, “somewhat paradoxical” to the surreal concept.

“Joe and I felt that work achieved with VP can inherently have a certain look to it – high contrast, glossy and sometimes betrayed by an artificial cleanliness,” Procter says. “We wanted to lean into heat, flare, under-exposure and halation, imperfections that one can inadvertently overcorrect in a controlled environment. A further desire to avoid the polished tropes of pop promos led us to a softer, more pastel aesthetic. Joe wanted to open naturalistic, drawing an audience into our ‘real’ location, before bending the rules of physics. We wanted bold, graphic compositions to juxtaposed with looser handheld moments to fluidly capture the dancers.”

The greatest creative challenge that Procter and his team faced was to light the set “in a way that felt naturally motivated” yet maintain the ability to shift the ambience and sun angle to match our time-lapse aesthetic – from dawn to dusk and into the night.

“As a cinematographer control is integral, but this relies fundamentally on collaboration,” Procter says. “In VP we see a meeting of two disparate worlds: a traditional film crew with Unreal Engine artists and VP team. We’re in a gestation period of collaborative learning, where roles are metamorphosing and overlapping.”

Despite already having VP experience, he was “apprehensive about the ambition of the piece”, within the time constraints of a promo schedule. “The size of our 3D landscape and the AI weather rendering demanded unprecedented processing power which was undoubtedly our most profound challenge,” Procter says. “Joe wanted to push the technology to its absolute limit, and we flew pretty close to the sun.”

Ask any serious or established filmmaker and they say that preparation is everything. For Procter, this is “never truer” than when using virtual production.

“As a tool, the prolonged prep time is better suited to long-form production, and we certainly felt pressured by our curtailed schedule,” he adds. “VP is a technology that epitomises the filmmaking process: without every single component working in harmony, the illusion is gone.”

Another challenge was managing the scale and perspective in a virtual desert to make it believable, especially when there are close-ups juxtaposed with wider shots.

“DNEG Volume at RD Studios is a 48’-diameter major-arc with a height of 20’ which allowed us to shoot wide vistas on our Caldwell Chameleon large format anamorphics,” Procter continues. “These 1.8x anamorphics marry the character of a vintage lens with the performance of modern glass. We chose a Scorpio45 Technocrane to enable elegant sweeping moves, whilst also allowing programmed planes, saving time on our shoot day.”

Nevertheless, VP doesn’t have all the answers and Procter says it’s “occasionally betrayed” by its limitations – “a visual language” of slow-moving shots. “We found that by increasing the frustrum size wider than our actual focal length we were able to achieve much faster camera moves,” Procter says. “Whilst our piece takes place in a singular vantage point, we achieved aesthetic diversity through the constantly shifting light.”

Virtual production meticulously orchestrated a barren digital canvas into a visually striking and palpably authentic desert landscape.

–

Words: Robert Shepherd