Pete Romano ASC explores the tech milestones and lighting kit developments that have impacted his work as a specialist in underwater shooting.

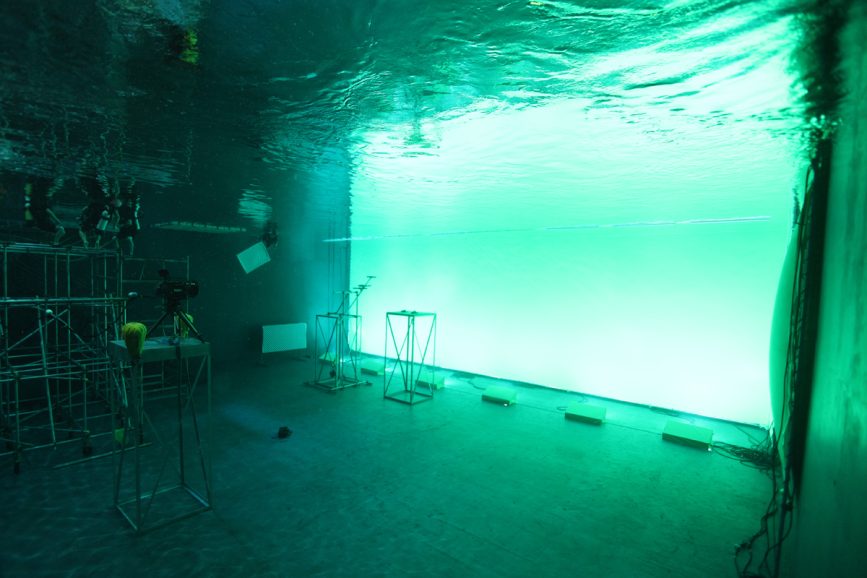

Working underwater combines several tricky factors. There’s often no, or less, natural light, space fades to blue over quite short distances even when it’s spotlessly clean, and taking lighting down there is, well, still tricky.

Those are questions Pete Romano ASC seems more than qualified to answer, having enjoyed a career in underwater photography ranging from Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home in 1986 and The Abyss in 1989, up to recent productions including CSI: Vegas and Obi-Wan Kenobi. “My former partner and I were the first ones to put HMIs underwater on Abyss,” Romano recalls. “That was a game changer for us, that was a milestone, and we’re still renting underwater HMIs to this day… You’d need a big bank of LEDs to overcome the light of a 4K HMI.”

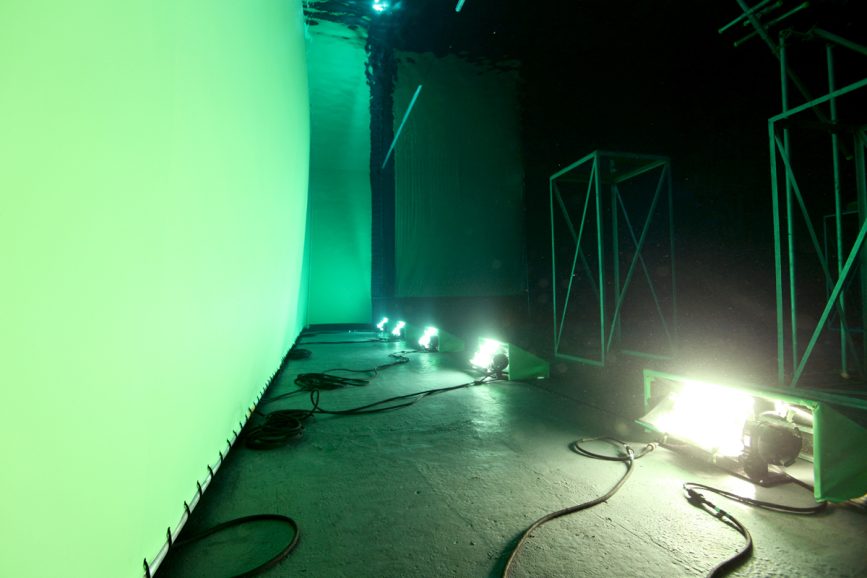

That notwithstanding, the convenience of recent lighting developments (and the huge sensitivity of modern cameras) have fomented change. “It’s changed since Abyss. There’s only one person who could have pulled that thing off, and he did it. Now we’re looking for some nice lights with a bit more output. We’ve been using tiny brick lights [the now-discontinued Litra Studio], only six by four inches and two thick. Those are extremely helpful.” The company’s stable also includes such industry favourites as Astera Titan Tubes in underwater housings, and, as Romano says, “We’re building cases for SkyPanel S30. They’ve become extremely popular, they’re very versatile.”

Design considerations for underwater housings include such practicalities as making the light sink, or at least be neutrally buoyant, to make underwater handling practical. “The light as you hold it is 15 pounds. We drop it in a box that we made out of three-eighths aluminium plate welded outside with a fan for cooling… but it still needed lead. In each one of our housings there’s a little brick of lead to make it balanced. It weighs 66 pounds before it goes in the water. That’s the law, you can’t change that.”

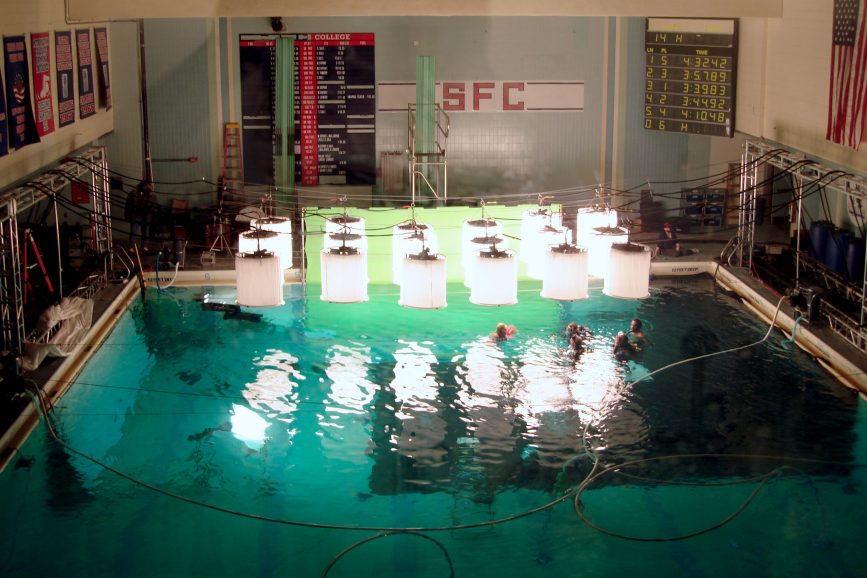

The majority of Romano’s work, he says, takes place in tanks as opposed to open water, a factor which can demand special measures if the environment needs to look natural. “The cleanest tanks I’ve ever worked in are in the UK,” he says. “One would be Pinewood, and one would be the Leavesden underwater stages. Dave Shaw, who runs the Pinewood setup, has it all dialled in. The heat, the filtration, everything. The flip of this is if you’re supposed to be in an ocean or a river that’s dirty. I have a witch’s brew I make up using dyes from one of the special effects houses in California. I mix a green and brown dye in a bucket, and I’d take that gross-looking stuff down to the set in a little water bottle. If it gets out of control, you’re in big trouble, but I’ve never had any big issues with that whatsoever.

The coordination often demanded when working in such a specialist area is what Romano describes as “my diplomacy hat. I’m going there to help this camera person. I’m there at their beck and call, to guide them and the director to get what shots they want. Sometimes they’ll be asking for things you can’t do physically, so you have to diplomatically say ‘here’s another idea that might work for you.’ I look at it like a collaboration. I’m not coming in like a five-hundred-pound gorilla to a crew that’s been together for months. It’s teamwork.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes