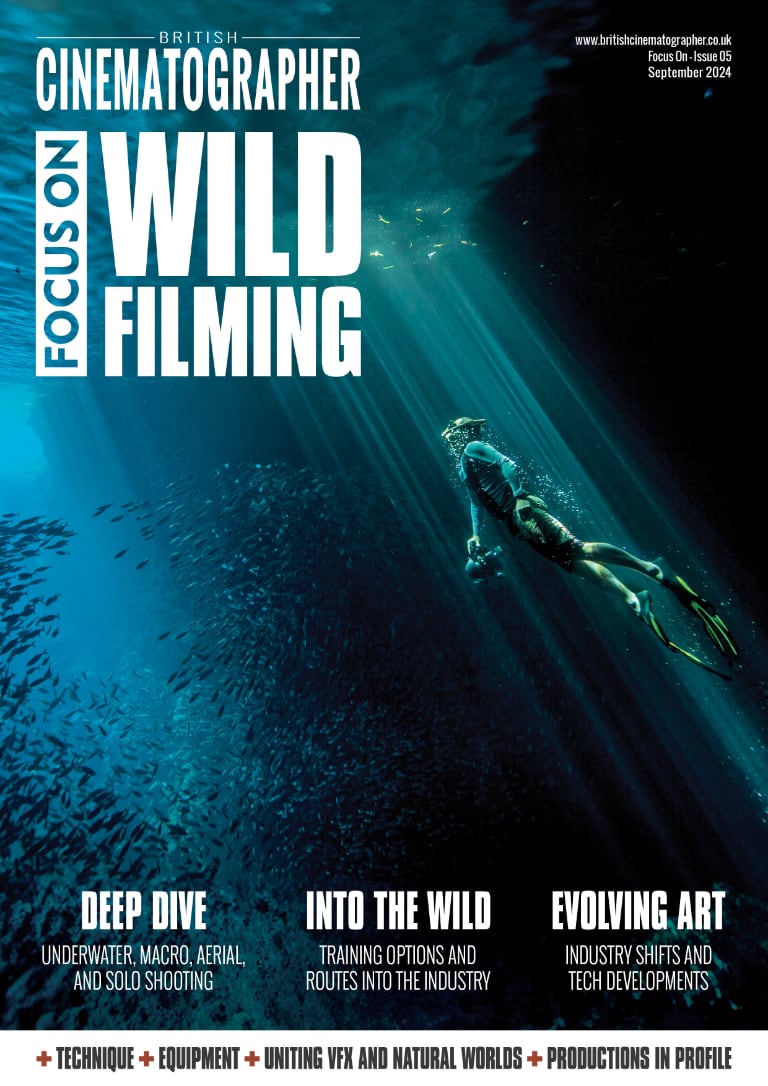

KITTED OUT FOR SUCCESS

Film and TV projects have long combined custom-built equipment with the latest high technology, and that seems even more common in natural history work.

The natural history field demands material that’s novel and achieves the sort of high-end gloss that’s become a baseline. Katie Mayhew describes it as “the blue chip look that everyone’s striving for, the sort of look that was created by the original Frozen Planet and Planet Earth. We have to create better and better sequences.”

Mayhew began her career, as is not uncommon in the field, without film school. “I went to Stroud college and did an art and design foundation course for a year, but I only specialised in medium format stills photography. I started as a runner at Films at 59 in Bristol. I was among people who had a full degree and a masters, and we all started off on the same foot. I worked my way up the ranks doing camera assisting work and finally went freelance four and a half, five years ago.”

Mayhew’s engineering experience began at Silverback Films in Bristol, where she recalls “we were forever developing new ideas in-house… having that experience of working where they have the facilities and the budget to do things gave me an insight into what I’d be able to achieve on my own.” Now independent, Mayhew is often commissioned to create equipment for specific setups. “I’ll build things to get the shot the producer wants. It’s all very DIY, slightly adapted pieces of kit ripped apart and turned into something else. One bit of kit doesn’t necessarily suit all needs, so you’re forever problem solving and bolting different bits of kit together.”

That equipment arises, Mayhew says, from a variety of places. “I work a lot with Kessler Crane, in the States, and also a Camblock system. I’ve rebuilt the Camblock to take the Kessler, so it’s now a hybrid. I swapped all the electronics out for Kessler systems, but you can do it all with your own stepper motors and a series of Arduinos if you want to go down that route. If I’m creating something for myself from scratch I use Arduino. It’s a brilliant thing to learn, then you can create lighting control systems, moco systems, and robots.”

Career highlights include specialist rigs for the BBC’s Wild Isles, with Mayhew contributing to five of the six episodes. “I worked on the adder sequence, butterflies, toads, spiders, bats, roe deer, tawny owls. For the adders we had to undersling an entire slider setup and be able to remotely operate it so the adders weren’t disturbed by our presence. For wood ants, we had to adapt the sliders and moco systems so we could poke through these ant highways, from the wide world down to the nano-world of the ants. We made jib arms that went on sliders with probe lenses.”

“At the moment,” Mayhew concludes, “I’m rebuilding my studio with a big robot for making lots of macro bits of plants. I’m forever creating and chopping up different bits and finding I’ve drilled a hole in the wrong place and have to do it again!”

Moco maestro

Mohan Sandhu’s career is just as hard to characterise. “It’s been such a random 10-year career,” he begins. “I design, build, operate and rent camera equipment for wildlife – anything that sort of slips between the cracks of regular rental house motion picture kit, from not-too-macro on small critters, to 20 or 30 times magnification stuff for moco rigs. I build a lot of underwater gear.”

Sandhu started out at Aardman, operating motion control equipment for stop motion shoots, “but I really didn’t consider engineering as a career until I finished the feature I worked on at Aardman… there isn’t a huge demand for stop-motion motion control operators. I started tinkering and building things while waiting for responses to letters and emails, then someone came along and asked if they could use the kit I was building in my spare time.”

Not many people’s spare-time projects involve multi-axis underwater motion control rigs, but Sandhu built one for Blue Planet II after previous projects with cinematographer Gavin Thurston. “He’s one of the big players, and we came up with a project together which took me about eight months to build. I built a carbon fibre crane, super lightweight. I thought ‘I don’t know what’s going on the end of this,’ then the first Mōvi [gimbal] came out. Off the back of that, Gavin was talking to Blue Planet II, which I, being very eager, tried to knock out of the park.”

Sandhu also found himself at Silverback, where he worked on “underwater kit and remote cameras for a bird project. The in-house second shooter wasn’t available so they asked if I wanted to go to Papua New Guinea for two and a half months on Dancing With the Birds for Netflix.”

The exigencies of working with animals, though, can scupper the most careful plans. “I built a bunch of different rigging systems, a remote pan and tilt head and a slider but there was no way we could use that. None of the subjects I filmed would tolerate that kind of movement. I wasn’t shooting much long lens, but on the CN20 the females would scarper just from zooming the lens, just from elements moving. You couldn’t even reposition the camera from the hide. Any slow reflection would be an issue.”

Sandhu’s most recent work involves the very small, though without sacrificing the opportunity to lose oneself in a spectacular image. “I’ve just built one that can do sub-micron moves. You could film on a microscope slide. You’re controlling the rig with joysticks just like a PTZ camera, then you look away from the monitor and realise a big move is half a millimetre. The other day I was doing a little move around an ant’s eye, probably about twenty-five-times macro, and you get lost in the monitor.”

Sandhu has, as he puts it, “done some crazy things. I’ve built four different treadmills for ants and beetles. Starfish are really problematic – they end up destroying coral reefs and they have to be moved out of the way, and they’re spiky, so I made barbecue tongs out of marine grade stainless. I remember being in the Namib desert chasing baboons around with an RC car. Nobody in careers advice at school told me it was a job to chase monkeys around with an RC car. This is my job. It’s surreal.”

Thermal imaging technology

At the other end of the scale, the drive for pictures to capture the imagination of new audiences pushes the world’s most refined technology to the limits. Anna Dimitriadis is one of very few people who have used Leonardo’s SLX-SuperHawk thermal imaging camera in natural history production. Launched in 2019, the camera is one of few capable of medium-wave infrared thermal images (as distinct from simpler shortwave, security-camera-style infra-red pictures) suitable for HD production.

Dimitriadis began early. “I think I did my first dive when I was 12. I’m half-Greek and I spent summers on the beach and in the sea. I started working in broadcast television before realising that my passion was wildlife, then I started doing everything that I could in order to reach that goal.”

Thermal imaging cameras have traditionally suffered limited resolution and image quality, but the SuperHawk is “1280 by 1024, which is pretty incredible really,” Dimitriadis enthuses. “The sort of detail you can get is incredible. It’s being used by the military, and they need to know if someone’s holding a weapon or a toy. The lens is 27-400mm with 15x zoom, so you can get in there, and it’s been absolutely mindblowing.”

Dimitriadis describes the camera body as an intimidating chunk of technology. “It’s 20 kilograms so you’re quite restricted. We’ve been using side mounts on land cruisers so you have it next to you on your tripod bowl. Getting it on and off is really tough. I have heard they’ve stripped one down and put it on a GSS [stabilised head]. I don’t know who, but I’ve heard through the grapevine of the natural history industry that it’s been done.”

Viewfinding with an Atomos monitor-recorder, Dimitriadis relied on idiosyncratic exposure controls specific to the medium. “The machine calibrates to the outside temperature. You’re then adjusting the contrast, you lock those settings, and your image doesn’t change. Otherwise, you’d be at risk of panning with the subject, and the temperature changes and throws your image out.”

Merely finding the subject, Dimitriadis points out, requires special measures. “It can be quite disorientating. You’re restricted to the view of the lens, and you need spotters with you who have thermal scopes. There’s a lot of ‘12 o’clock! One o’clock!’ What one person can see with their eyes you can’t see yourself. I think we had two thermal scopes and they were really essential for keeping near animals.”

Existing in the unreal world of thermal vision, meanwhile, is an odd experience in itself. “It can make you quite disconnected from your subject because it doesn’t look real,” Dimitriadis muses. “I’ve sat metres away from a pride of lions which are on a kill. Someone flashed a torch nearby and I was drawn back. You spend a lot of time looking through the camera as your main directional source and it can be really confusing at times.”

The upsides, though, are impossible to deny. “I was able to build a connection with a cheetah 20 metres away, sleeping. It means you’re ready as soon as the sun rises – you don’t have to go out and find a cheetah again. If you can stick with an animal all night the chances of getting the behaviour you want is much better.”

Wildlife production inevitably contrasts that sort of high technology against the privations of field work. “Sometimes we stay on the vehicles at night and we don’t go back,” Dimitriadis recalls. “If we do go back we’re going back to a camp… if not, you just shower next to the vehicle with a bucket!”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes