Filmmakers today are spoilt for choice with the variety and quality of cine lenses available, even if their evolution hasn’t been as dramatic as other camera technology over the years.

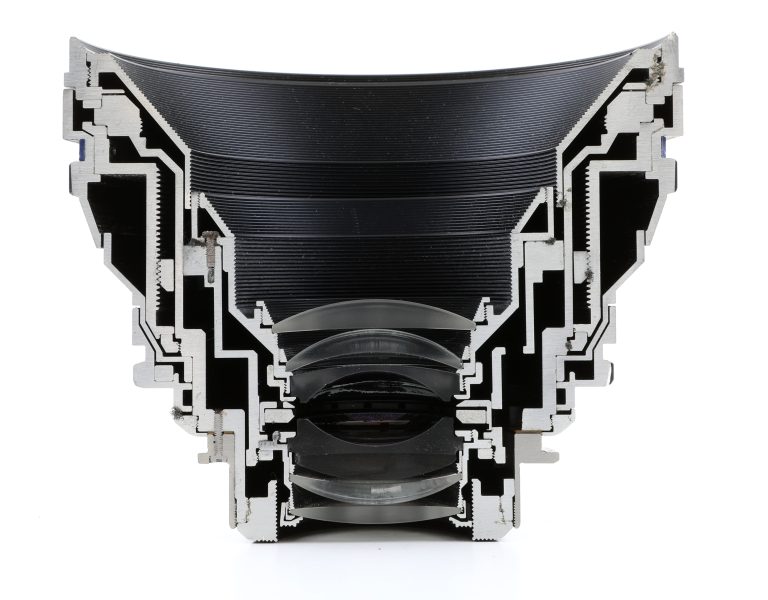

Given that lenses are the part of camera technology that have undergone the fewest fundamental changes in the last decade or two, the modern fascination with them isn’t necessarily something anyone would have predicted. Now, the desire for the best of historic behaviour, combined with the sheer capability of modern technology and the desire to cover ever larger formats, has created a lens market characterised by sheer choice.

With cinematography credits since the early 2000s, Nicole Hirsch Whitaker ASC has witnessed the whole process and, as she says, enjoys the explosion of new options. “Compared to when I started shooting, there are so many choices. I’ve found over the years, there are some DPs who always use the same combination every time they work, and change other things. But I find it keeps things fresh when you can find a new type of lens. It’s not like there’s a lens manufacturer I like more than others. I’ll have a conversation with the camera house and they’ll show me things I’ve never even heard of.”

SENSOR-SATIONAL SHIFT

If there’s a single factor which has imposed an absolute technological requirement for new lens choices, it’s not a sudden change in optical design capabilities – it’s the push toward larger sensors. Whitaker’s own preferences have long tilted in that direction: “I’ve pretty much stuck with large format in the last few years. I love the falloff, I love that you can shoot a wide lens and not have to be wide open, especially on TV projects where we don’t have time to do 10 takes for focus. I can shoot at a 2.8/4 split, even a 4/5.6, and the falloff is so good on the large format that I don’t miss being wide open.”

While those larger sensors might make room for more pixels, the drive for easily promoted resolution numbers in camera design is something that Whitaker remembers being gently worked-against by leading practitioners, even before massive resolution became trivially available. “When we started with digital most DPs were using vintage glass to knock down the sharpness – Kowas and Baltars and Super Speeds, things which were a bit mushy when they’re wide open. So, I started shooting deeper stops, especially the Super Speeds, which fall apart when they’re wide open in digital.”

Modern lens designers have reacted to that situation with a drift toward glass which deliberately leans away from sharpness and flare suppression. “Now, with the newer lenses which are being built, they’ve done something to add some softness to it,” Whitaker confirms. At one time, she goes on, the same ends might have been achieved with filtration: “If, let’s say, I’m on a project and the glass is too sharp, I’ll use a filter to knock it down. [Tiffen’s] Glimmerglass is a favourite. The [Schneider] Hollywood Black Magic is kind of cool too, but I’m not having to filter as much now.”

VINTAGE VS. MODERN

Practicalities step in, too, given that vintage lenses may have been designed in the expectation of being used mainly at medium apertures. Modern productions may not have the same option to light for very high F-numbers, even if the creative desire to do that exists, making more modern designs desirable. “I think there’s some real beauty in vintage glass, but I find the new anamorphic lenses hold up really well wide open. With the older glass, I do find you need to shoot around a 4 or a 5.6. Hawk has really perfected the anamorphic – Panavision and Hawk both. There are other anamorphic lenses out there too now, those two are just my favourites. I remember shooting with the C and E Series on commercials back when we were shooting film. I know everyone loves the T Series with digital.”

That caution over excessive sharpness occasionally jostles against the ambitions of distributors keen to promote a service with big numbers. In Whitaker’s experience, though, producing entities have often been willing to moderate their demand for pixels given a careful explanation of creative context. “I remember when I first started shooting with the Alexa, trying to convince digital effects people that it was ok, even though the pixel count wasn’t quite as high as the other cameras.” That notwithstanding, as the offset between what the highest-resolution cameras can do, and the finished results which land in the lounges of the audience, can be profound. “You get in the bay and you have this beautiful 6K or 8K image. Then they finish in HD!”

One recently emerged option involves not so much choosing an existing lens, but choosing a hypothetical lens and willing it into existence. Projects demanding uncommon lenses on large formats have meant both shipping glass around the world, modifying existing designs, and even putting together new options, something Whitaker recounts doing in part due to the huge popularity of large-format anamorphic. “On Shining Vale we shot Hawk Vintage ‘74 anamorphics – they were so expensive we could only afford one set for the show,” she recalls. “They’re beautiful. And when I was shooting in London last year, I had to bring glass from the US for Bad Sisters, then I went down to South Africa for another production, and there was no LF glass available, not at Panavision London or in LA. We had Hawk build us glass.

“We were prepping that show during the pandemic, the director and I, for about a year. We were booked very early, about six months before it was on the ground. We had a long conversation about how we wanted to shoot the show. We really wanted to shoot anamorphic, but it’s a live action adaptation, and we wanted something where you could almost touch the lens then go to infinity. We reached out to Hawk, and they built a Mini-Hawk for large format for us.”

ANAMORPHIC APPROACH

Whitaker’s next project, as she says, is also likely to be anamorphic – but anamorphic of a very different lineage. “I’ll be working with ARRI for the first time in a while. I haven’t shot with their lenses but they have these really beautiful anamorphics which were used on The Batman. I’m really excited to work with those.” It’s an option almost symptomatic of the state of lenses in 2023, and an opportunity Whitaker values. “For a while it was hard to get people to sign off on anamorphic. There’s an idea that VFX costs more on anamorphic, but from what I’ve heard from my VFX supervisors, it’s not always true.”

But as Whitaker concludes, an approach of choosing unusual lens options, or even picking a lens for each project, is far from universal. “Two of my favourite cinematographers in the world shoot Master Primes – Deakins and Chivo. They mostly don’t shoot anamorphic, they prefer spherical. Then there are other DPs who are adamant fans of anamorphic. I just worked on a show where there were seven sets of lenses. It was funny in a way – ‘this lens is fun for this scene!’. You could pull out uncoated Super Speeds. It’s something that’s really fun. Sometimes you can do that through filtration as well, but I just love being able to play and see the different qualities of the different lenses. I haven’t used the same lenses twice on any of the shows I’ve ever been on!”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes