Gaffers Carolina Schmidtholstein and John ‘Biggles’ Higgins take us on a guided tour of how they approached lighting productions of various genres and sizes with creativity and originality to realise the director and cinematographer’s visions.

Camera departments constantly juggle a thousand challenges, but there’s one goal that’s almost universally sought, but rarely discussed in isolation: sheer originality. The drive to photograph a story in a way that’s interesting and new, or at the very least not played-out and hackneyed, is probably why there are as many ways to make movies as there are movies. It’s a situation demanding a certain amount of creative agility which gaffers John ‘Biggles’ Higgins and Carolina Schmidtholstein deal with every day.

Higgins’ most recent experiences represent something of a case in point. “The last big film I was involved with was Mickey 17, directed by Bong Joon Ho, who did Parasite. That was a very big production for Warner Brothers, with Darius Khondji ASC AFC. Now I’m in Ireland, doing a film called The Watchers which starts in three weeks. Mickey 17 is science fiction. The Watchers is a horror.” While switching genres might be all in a day’s work, though, the demand for a camera team to quickly comprehend then support the varying approaches of different cinematographers comes up often in any discussion of how a camera team works.

“No two cinematographers will approach the same task the same way. They’ll always do it in a different manner,” Higgins confirms. “In my position I have to try to work out what the cinematographer wants and get it as near-as-dammit there, and the cinematographer can do the final tweaks. There are DPs who like things very hard and like to work like that, there are DPs who love the quality of tungsten… you soon find out what the cinematographer likes, and when we’re going for coverage, it becomes sort of a shorthand.”

There are many routes to that sort of utopian creative symbiosis, though Higgins has come to recognise a few as particularly useful. He describes something “most DPs use. The production designers often do concept art for the sets, and that’s an invaluable guide to setting a look. It mightn’t be exactly the same, but you have a great starting point. You see what the [practical] fixtures are like, you get the lamps they’re designing.”

What should be a creative collaboration is inevitably interrupted, at least sometimes, by the sheer technology that’s involved in camerawork, and, as Higgins says, there are some peaks that more convenient, modern designs are

yet to conquer. “What we didn’t have, until recently, was good, reliable, and high-output LED fresnels. That’s being rectified all the time. Rosco owns a lighting manufacturer called DMG, and they’ve brought a fresnel out, and the ones I’ve been using as a fresnel and as a softlight are by Fiilex. The Q10 is the biggest unit they do and it’s very impressive. I first saw the Q5 [at] Cirrolite and it was the first one that demonstrated characteristics of a proper fresnel.”

Replacing a tool with a better equivalent doesn’t necessarily alter the result, or at least probably shouldn’t. A less traditional part of the gaffer’s remit, meanwhile, involves reworking or even custom-building practicals, necessarily involving new designs for every project. As Higgins points out, it’s a crucial issue in an era of highly designed productions with mobile cameras that might often rely on practicals for sheer illumination. “The practical part of the lighting department is no longer just background. Practicals have become a very big element that sometimes production overlooks in their budgeting. There was one film which – will remain nameless – where that was completely overlooked. I had 16 guys in the studio just doing practicals, and we had to hit it hard to get everything ready on time. That’s not free.”

Organic process

Even traditional approaches vary in sheer scale. The upper end of that scale has risen significantly over the last decade, and it’s no surprise to find an example at Cardington Studios, famous for its pair of vast, early-20th-century airship hangars which are among the largest interior spaces in Europe. “We couldn’t put a silk over the whole roof area – it was just impossible to do,” Higgins recalls. “So, we worked out a scheme of lightboxes. We had ninety 20-by-20 softboxes which gave us a beautiful light. Darius liked the setup. We used an ACL panel, which has very good output and colour rendering but is significantly cheaper than a SkyPanel. We had individual control on over a thousand lamps, each individually controlled and mapped. It was great.”

Achieving that end required what Higgins calls “a big engineering thing,” the like of which might not appear on more than a very few productions. “The first thing we had to do is put the infrastructure in for nearly four hundred chain motors. There are fixing points, but every time you put a rig in there you have to put the whole infrastructure in and every time you finish you have to pull it out. We had so many constraints – we had structural engineers involved with weights, we had to do method statements, and everything had to be tested as we went along. At the apex that stage is 180 feet high! We were scheduled to shoot there at the end of October, early November, and we started prepping in August.”

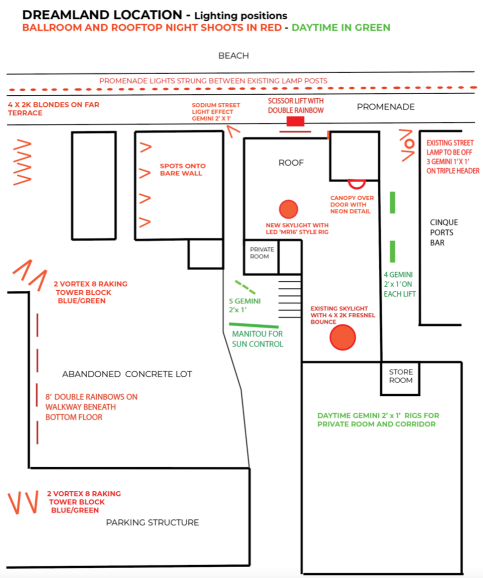

By comparison, illuminating an exterior with festoons of fairground-style incandescent lightbulbs might sound straightforward, although, as Higgins says, distance creates considerations of its own. “I did a film a couple of years ago [Empire of Light, shot by Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC] where the director [Sam Mendes] wanted festoon lights all around Margate beach, around

the promenade and coast road. It was a mile and a half. We did a test so we knew the distance between the bulbs, and it meant there were 6,000 bulbs around the beach, each 60 watts. That’s 360 kilowatts, so that’s three or four generators. It just wouldn’t be possible to do it.”

The solution involved new technology standing in for old. “Each lamp post had a small electrical supply to it, which the council were happy for us to use,” Higgins explains, noting that the amount of power available might not have supported the traditional approach. “The only way we could do it was with warm white LED clear bulbs. We did a test at ARRI with a tungsten bulb and an LED at different levels on dimmers and we had the DIT there with a histogram, and it was very reassuring because the histogram was exactly the same for the tungsten and the LEDs. We got the warmest LEDs we could find. They are not tungsten bulbs, but you’d bet they were. The council supply was sufficient that we could run everything on their system.”

Regardless the technological approach, or the practical demands and the decisions those might impose, Higgins concludes by reinforcing the idea that accommodating the particular needs of a production is not fundamentally technological; it’s interpersonal. “Sometimes I share an office with a DP and sometimes I don’t, but just by talking through things and developing a look, the DP will say I like that, but I’ll make it a bit different. It’s an organic process.”

The importance of that understanding is so huge, and so widely recognised, that it’s no great surprise to find repeat collaborations in filmmaking. Just last year, gaffer Carolina Schmidtholstein worked with Hélène Louvart AFC on the historical drama Firebrand. Starring Jude Law and Alicia Vikander, the film premiered at Cannes in May 2023. At the time of writing, Schmidtholstein and Louvart were collaborating again on The Salt Path, a very different story in a contemporary setting. Schmidtholstein’s wider credit history broadens the scope even further, from the theatreland whodunnit See How They Run for Disney Plus to the extensive exteriors of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry.

Firebrand demonstrates how much techniques might vary even within the consistent look of a single production. Schmidtholstein remembers the film as “something unusual. It was quite a dark look, and we had a director [Karim Aïnouz] who was very much into colours. It was not your standard Henry VIII period costume drama. It’s not like we had crazy colours, it was the ambience that had a big palette and certain reflections would catch that. We had a big rig, covering all angles in the ceiling so that with a desk op, it was easy to control in all directions. When we would turn around, it was very easy to light without re-rigging everything.”

That sort of convenience necessarily demands preparation, and Schmidtholstein worked with a rigging gaffer and a team who would, she says, “be two weeks ahead. Before we started filming, we had at least four weeks pre-light, so I would be making the plot, and they would start rigging. I would check and while we would be filming in the first room, they’d pre-light the

second room and so on. It was almost like stages. There was a lot of work in the scheduling.”

Outdoors, the approach, and thus the workload, changed. “For the exteriors, it was on the same compound, and to shoot at the right time of day we were very involved in scheduling. On exteriors we would mainly use butterflies, reflectors, and stuff. We had occasionally also the LED 9-lights, but the exteriors rarely used added light. It was rather shaping it with butterflies and bounce. There’s also a lot in the grading to keep it still in that mood of low level, or contrast, so we used a lot of negative fill as well.”

Switching it up

For ...Harold Fry, photographed by Kate McCullough ISC, things were different. The crew relied on natural light almost exclusively since, as Schmidtholstein says, “80, 90 percent of the film was outside. It was Jim Broadbent walking from one end of the country to the other, and other than the last three weeks when we filmed the interiors in London, we filmed in chronological order from south-west England to north-east Scotland. On the road it was something like two transit vans of gear. We were four, maximum six. Often it was three of us. We had a minimal kit.”

Here, Schmidtholstein enthuses about the ability of reflectors to handle a wide variety of situations, particularly Lightbridge’s CRLS panels. They found use working with available light on …Harold Fry, but also on the vastly different Firebrand, where the crew combined CRLS with Dedolight’s PB70 parallel-beam system, creating what Schmidtholstein calls “a really realistic kind of sunlight. It’s a 1.2kW HMI, so you can run it from a mains socket, but you get enormous light out of it. On Firebrand we used four of them, all that’s available in the UK. The reflectors are a metre square and come in four different strengths, which is how you quickly go from a hard light to something a bit more soft.”

The reflector system worked particularly well on Firebrand, given an ambition to light through the windows but also to see through them. “I suggested that we build scaffolding tower so we could work off the platform. The beauty is that the light stays on the floor, and you send it straight up to a reflector, and you can tilt it down so much you can get a very steep angle. Again, you can look out the window and you don’t see the light. You don’t have to bring them far away from the window to get them out of shot. There aren’t that many lights you can tilt down so much.”

See How They Run worked very differently, taking special advantage of the otherwise grim pandemic shutdown of theatrical venues. “It was in the second lockdown, and it took place in the theatre world,” Schmidtholstein says, describing the storyline as “like the Agatha Christie Mousetrap story in a way – behind the scenes, a whodunnit taking place in the theatre world of London. The theatres were all empty and nobody was working, and we had sparks from the theatre world, so it was again a big crew, with a rigging gaffer, pre-lights, and studio rigs.”

All of this was organised at very short notice, a practicality that might make two similar jobs feel very different. “Another gaffer dropped out and I was taking over, so my prep time was two weeks, or something silly. It was a tricky one,” Schmidtholstein admits. “COVID restrictions were a thing, and that’s why we didn’t have as much time as they wanted. It was also such an ensemble piece. With 12 main actors, it was really important to get all the angles of all the people. It was a lot of turning around and turning around again – lots of different angles. It was fast because we had to be really quick turning around.”

Much of See How They Run would be shot on stage, representing something of a return to traditional techniques. “It was more conventional in that we had HMIs on cherry pickers and 10Ks in studios, and lots of LED, either SkyPanels or Geminis, in the studio rig. What I found interesting was mixing into the theatre world. I had some theatre sparks and I had two radio systems, one talking to the theatre sparks for what they had rigged for the theatre and augmenting it with our lights.”

No matter how complex things become, though, the most telling comparison is to smaller, simpler projects, albeit often with a very specific creative intent. “Every now and again I do films for artists – it’s my little pleasure on the side,” Schmidtholstein says. “It’s something really different where you don’t have a story and you don’t have continuity issues. It’s more like playing with light, creating interesting moods and shadows. I love lighting through textiles, for example, and I like to move the textiles to give it another level of movement and change and alteration.”

In a field which covers this much ground, perhaps the only preparation anyone can do is to bear in mind just how wildly the task might vary from one engagement to the next. Despite the inevitable influence of fickle creative opinion, though, Higgins concludes with a feeling that while the world of equipment has seen some upheaval, the underlying intent has never changed. “LED is great up to a certain power level. It goes quite quickly from LEDs like the DMG Dash, up to 200kW SoftSuns. I think for the foreseeable future there’ll be a place for the 18K HMIs. But in the end, the basics of lighting haven’t changed in a hundred years. The principles are the same.”

–

Words: Phil Rhodes