Virtual production technologies, especially LED volumes with their ability to recreate places anywhere on (or off) Earth, provide significant environmental benefits over conventional location filming.

Ben Saffer is a cinematographer with a diverse range of experience shooting features, short films and brand content. He has delivered talks on virtual production for Final Pixel Academy’s VP taster days at ARRI Stage London and has worked in the camera department of films such as No Time to Die, where close-ups for an Italian car chase were accomplished on an LED volume.

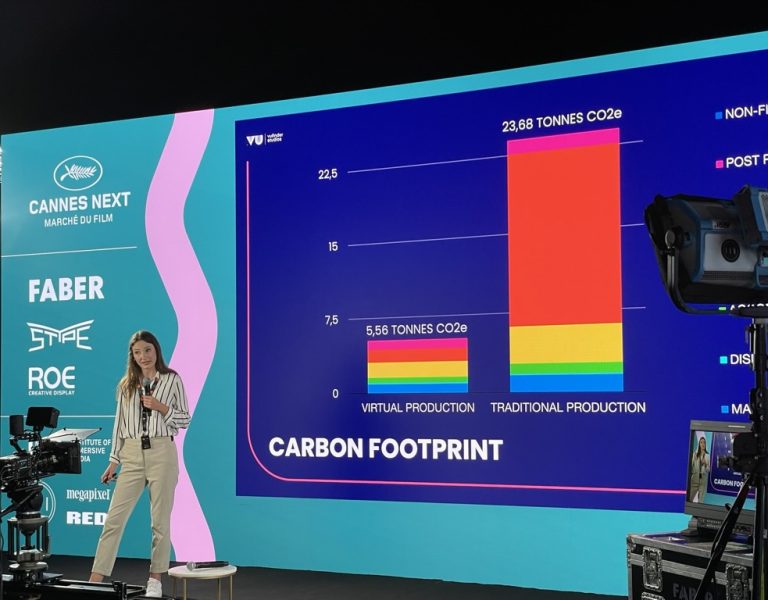

“I firmly believe that more productions will adopt VP for sustainability reasons,” says Saffer. He cites a 2022 report by Sony Pictures which analysed two productions, comparing CO2 emissions on location versus VP. It found a 52-76% emissions reduction from using virtual production.

Another report on this topic was authored last year by Professor Declan Keeney at Ulster University. “VP technology can greatly reduce the carbon footprint of this fast-growing screen sector,” the report states. “In film production alone, this can be between 20% and 50% in current large-scale hybrid productions, with further efficiencies possible with more research and development investment to push savings higher.” However, it also cautions that there are “some gaps in our understanding”, noting that “the environmental impact of creating and ultimately disposing of large amounts of LED panels and some other associated high-tech equipment is not yet well understood.”

Keeney’s report suggests that carbon calculators “are a good starting point that now need to factor in the nuances of VP’s technology stack.” It adds, “The carbon footprint associated with extensive cloud computing, rendering and data storage is not well understood in the creative industries.”

Caveats aside, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of VP’s environmental benefits. Saffer gives a recent sci-fi short he photographed as an example. “While a traditional set could have been built, it would have demanded significant materials and labour, and constructing the set with flats would have resulted in a lot of waste post-production. Also, as it was related to a video game IP, we were able to utilise some existing 3D assets, streamlining and expediting the process while minimising waste.”

Saffer also cites a commercial where international travel was obviated by a volume shoot: “This approach not only reduced our carbon footprint but also simplified logistics and reduced costs.”

Chris Bouchard is a virtual production supervisor whose experience includes working with The Mandalorian team at Industrial Light & Magic, supervising TV commercials for Red Bull, Lego and Mastercard, and supporting VP shoots on films and TV including Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania, Barbie and Hijack. He agrees that reduced air travel is a key benefit of the technology. “Less obvious is all the trucks and diesel generators required for location shoots and unit moves,” he adds.

“I recently supervised a shoot for a TV show which wanted to film a presenter and cast in five different parts of the world: desert, jungle, tundra, etc.,” says Bouchard. “Using virtual production enabled us to bring the locations to the studio as a 3D virtual world, and with much greater quality – and immersion for the director and talent, I should add – than would have been possible with green screen.”

As the Ulster report found, VP is not without its environmental impact though. “Indeed there is significant power draw for the LED volume tiles, especially if a larger stage is required,” Bouchard notes, “and manufacturing of computer hardware and LEDs also has an impact. Of course, as the hardware is re-used for the next film, it could be said to be less wasteful than building a large set and then trashing it.”

When British Cinematographer discussed virtual production with director-DP Brett Danton for our 2022 supplement, he brought up the benefits of being able to repurpose and reuse assets. “What’s better,” he asked, “if you can go to a location and scan it in, and use it in a car commercial – in five different commercials – and you’re only sending five people to that location… as opposed to sending 100 people for a week and trampling it and killing it?”

Danton shot such a project in Namibia with executive producer Anissa Payne. “Our crew managed to LiDAR scan various areas, along with video and stills footage. This approach didn’t require a product vehicle to be shipped in and kept the equipment we used to a bare minimum,” says Payne. The crew required only four small vehicles and relied entirely on batteries rather than bringing a generator. “Although Namibia wasn’t without its difficulties and copious amounts of sand everywhere, we managed to achieve everything we set out to do without causing any undue stress on an already delicate landscape.”

Payne contrasts this with a comparable production in the Far East which was shot conventionally: “It required at least 30 crew and clients (nearly three times more) flying in from the UK, all of whom needed to be accommodated and transferred to and from locations each day for a two-week period. This also included shipping in and transporting three vehicles which required additional manpower and footprint.”

“While there will always be a majority of productions where shooting on location is creatively and practically the best option,” says Saffer, “many projects can reduce their environmental footprint by strategically using VP. For example, conducting pick-up shoots on a volume stage rather than returning to a remote and costly location is often better for creativity, budget, and the environment.”

Someone who recently did exactly that is Gareth Taylor, a cinematographer, filmmaker and photographer based in Los Angeles. “Earlier this year I shot pickups for a film that was shot on location the year prior,” he explains. “The director re-cast an actor who was involved in a driving scene. Instead of going back on location, we opted to film on a stage in front of an LED wall. This offered many advantages. First, it saved a considerable amount of time since we didn’t have to reset the vehicle after each take. Secondly, we did not have to drive production and picture vehicles to a practical location, saving a lot of fuel. Thirdly, by shooting on stage rather than using a process trailer, we had a smaller crew which saved production money.”

Taylor believes that more productions will turn to VP if it saves them money. “Unfortunately, I think only a small fraction of those are looking at it from an environmental point of view,” he admits. “Cinematographers and directors love the control it gives them over continuity and consistency. Actors prefer being in an environment where they can see the background rather than having to imagine it when doing green or blue screen.”

“The trend is to reduce emissions further,” says Bouchard, “with lower power-usage panels being released and smaller-sized LED volumes which require significantly less power than the large volumes that sprang up during the pandemic. For example, often 360° surrounding LED walls are only required in practice for one or two shots in a month-long shoot. So for VP backdrops, it’s much more effective to use a screen 1/8th of the size in many cases – unless reflections are the reason VP has been chosen. As the industry learns to use the tech effectively, I think we’ll see many more efficiencies and much lower power requirements for the hardware too. It’s still early days.”

–

Words: Neil Oseman

Comment / April Sotomayor, head of industry sustainability, BAFTA Albert